Glacial Features of the Huntington and Northport Area, Long Island by

advertisement

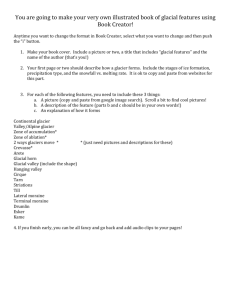

Long Island Geologists Field Trip November 3rd, 2002 Glacial Features of the Huntington and Northport Area, Long Island Notes and Road Log by J Bret Bennington Department of Geology Hofstra University Introduction This field trip is an excursion around the necks of the north shore of Long Island in the Huntington-Centerport-Northport area. The objective of this trip is to illustrate the distinctive topography of western Long Island and relate this topography to a variety of glacial processes that accompanied the advance of continental glaciers some twenty thousand years ago. The region of Huntington Township, which encompasses the north shore from Cold Spring Harbor east to the border of Smithtown, is characterized by wide peninsular extensions of land called necks separated by deep, finger-like harbors (Fig. 1). The land of the necks is underlain by a complicated mixture of glacial deposits which include outwash, till, loess, as well as older Cretaceous age sediments. The southern margin of the necks is bounded by an east-west trending terminal moraine ridge, which forms a line of hills divided into arcuate segments. South of the moraine ridge the land is formed from elevated meltwater outwash fans that coalesce to form an outwash plain that slopes gently to the south (Fig. 2). North of the moraine ridge the land of the necks is extensively dissected by steep-sided, relatively narrow valleys (Fig. 3). These valleys are unusual in that they begin and end abruptly, trend both uphill and downhill, intersect oneanother, and lack large drainage basins. Many north shore valleys do not host flowing streams and show little evidence of ever having hosted a stream. These valleys are completely absent south of the terminal moraine ridge, although several of them do breach the moraine to form broad, shallow outwash channels incised into the outwash plain. The unusual, deep valleys of the necks are glacial tunnel valleys, incised into the moraine by meltwater flowing within and below the base of the glacier (Fig. 4). These tunnel valleys were a major conduit for bringing meltwater to the front of the glacier. Meltwater streams exited over and through the terminal moraine, depositing sediments across the outwash fan. Our journey today will take us across the landscape of the necks. As we drive from Caumsett State Park southeast to Huntington Village and then east on route 25A we will traverse the moraine passing into and out of several tunnel valleys (Fig. 1). At Centerport we will ascend south along Stony Hollow, a major tunnel valley that breaches the moraine ridge (Fig. 5). Crossing the terminal moraine we will continue east along the upper margin of the outwash plain, stopping to stand on the crest of the moraine in East Northport. After a quick tour of a housing development built on the moraine ridge we will travel northward, descending along another major tunnel valley back to 25A. From here we loop westward, following the paths of tunnel valleys to our second stop on Waterside Avenue in Northport. Here we will examine the kame and kettle topography typical of the hills formed on the moraine as the glacier melted back. Our third stop will afford an overlook of Eatons Neck and the Ashroken tombolo, as well as Steer’s Pit, the remnants of a large sand mine (now developed). Finishing our westward loop we will descend to Northport harbor along Main Street, another steep-sided tunnel valley, before returning to 25A and Centerport. If time permits, a fourth stop will allow us to view the gap in the moraine created by Stony Hollow from a vantage point in Centerport harbor. 1 km Figure 1. Field trip route through Huntington-Centerport-Northport area. Figure 2. Topographic profile across the Northport moraine. 1 km Figure 3. Map of the Northport area showing major morainal features and tunnel valleys. Figure 4. Cartoon showing position of glacier and paths of meltwater relative to the moraine. Road log Mileage 0.0 Description Entrance to Caumsett State Park at Lloyd Harbor Road, Lloyd Neck. Lloyd Harbor Road occupies a narrow east-west tunnel valley that separates Lloyd Neck from West Neck to the south. Lloyd Neck takes its name from the family of James Lloyd, who purchased the land encompassing the neck in 1676. Previous English owners had acquired the land from the Matinecock Indians, who called the area Caumsett, meaning “place by the sharp rock”. James Lloyd leased the land to his son Henry in 1711, who built a small manor house which has been restored and can be seen just a few hundred yards east of the entrance to the park. Henry’s son, Joseph Lloyd, built a larger manor house after Henry’s death in 1763, which is seen just west of the park entrance on the north side of Lloyd Harbor Road. During the Revolution, the British occupied much of Long Island, building a small fort (Fort Franklin – named for Benjamin Franklin’s Tory son, the Royal Governor of New Jersey) on Lloyd’s land. Joseph Lloyd, a patriot, fled to Connecticut for the duration of the war. At the easternmost point of Lloyd Neck is a large glacial erratic called “Target Rock”. Legend attributes this name to the use of the boulder as a gunnery target by British warships operating in Long Island sound during the occupation of New York. (Bill Bleyer, Long Island, Our Story) 0.2 0.6 1.4 2.0 2.7 5.1 Joseph Lloyd manor house. Turn onto West Neck Road. West Neck Road is an artificially built tombolo connecting Lloyd Neck to West Neck. West of the tombolo is Cold Spring Harbor, east is the salt marsh at the end of Lloyd Harbor. Road ascends hill onto West Neck. Small kettle pond on left. Large erratic on east side. Kettle ponds on east side of road. Turn left (east) at intersection of West Neck Road and 25A – Huntington Village. Huntington is Long Island’s fifth oldest town, originally encompassing lands purchased in 1653 between Northport Harbor and Cold Spring Harbor. During the Revolution, Huntington was a center for Patriot unrest, to which the British responded by making the town a major garrison. Patriot harassments induced the British to burn the local Presbyterian Church and to build a fort over the town cemetery. At the head of Huntington Harbor is the town of Halesite, so named because it was here that General Washington’s spy Nathan Hale was put ashore to begin his famous mission (Hale made his way to New York where he was caught and subsequently executed on Sept. 22nd, 1776.) (Long Island, Our Story) 5.5 6.0 Old burial hill cemetery and site of British fort in 1782. Intersection of 25A and Park Ave, a north-south trending tunnel valley. Note large glacial erratics in Huntington Town Park. From here 25A ascends out of the tunnel valley and up onto the top of the moraine. For the next 1.7 miles, 25A travels across a relatively flat surface atop the moraine. It is not known why so much of the moraine north of the terminal moraine ridge is apparently peneplained (flat-topped). However, the fact that most of the morainal deposits are capped by till suggests that this flat surface may have been formed as glacial ice flowed over and across previously deposited outwash during the maximum extent of glacial advance. 1 km Figure 5. Map of field trip route in Northport area showing location of stops. 7.7 8.6 8.8 9.2 25A descends into an east-west tunnel valley segment. Centerport and Centerport Harbor. Suydam Homestead on south side of road. This is a typical eighteenth century Long Island farmhouse. Turn right (south) onto Stony Hollow Road. Stony Hollow is a major north-south trending tunnel valley that appears to be connected to both the Centerport and Northport harbor valleys. The head of Stony Hollow valley breaches the ridge of the moraine, where the valley becomes a shallow, widening outwash channel that meanders broadly to the southeast. Near the top of the valley you will notice the abundant cobbles that give the valley its name, which are derived from the till capping the crest of the moraine. Just east of Stony Hollow is Sandy Hollow, a shorter valley that does not extend south to the moraine ridge and thus only exposes the sandy outwash sediments lying beneath the capping till. 10.0 10.2 10.6 11.0 11.6 12.0 12.3 Upper reach of Stony Hollow – note the abundant cobbles lining the driveways and yards of the houses. Exit the Stony Hollow tunnel valley onto the broad, flat surface of the outwash plain. Turn left (east) onto Pulaski Road. Drive along the level topography of the outwash plain. Turn left (north) onto Elwood Road. Notice that the road to the north gently rises approaching the crest of the moraine. We are now climbing the slope of an outwash fan. The moraine ridge is visible as the tree line in the distance. Note the water tower positioned on the ridge for maximum elevation and water pressure. Northport High School, corner of Elwood Road and Bellerose Avenue. Turn right (east) onto Bellerose. Bellerose Avenue follows the crest of the moraine from here to Larkfield Road. Hill on the crest of the moraine. Note the abundant cobbles from the capping till. Intersection of Bellerose Avenue, Larkfield Road, Laurel Avenue, and Vernon Valley Road. Vernon Valley is a tunnel valley that descends steeply to the north. The intersection marks the point where the tunnel valley breaches the crest of the moraine. To the south the landscape is flat across the outwash plain. Continue east on Bellerose Avenue. Note that the elevation of the outwash plain to the south of the crest of the moraine is higher than the elevation of the moraine north of the crest. This topographic inversion forms because the buildup of outwash deposits at the front of the glacier is greater than the accumulation of ice-contact deposits on the glacier. 12.5 Public supply well on south (right) side of Bellerose. 13.1 Veterans Memorial Town Park, East Northport. Park and climb up to hill behind soccer fields and handball courts. Stop 1: Veterans Memorial Park, East Northport The fields of this town park are built on the top of the outwash fan where it is in contact with the crest of the moraine. Till is exposed in a shallow gully at the hilltop. To the south (downhill) the gentle slope of the outwash fan is partly hidden by trees and houses built upon former farm fields. This point marks the terminal advance of glacial ice during the most recent episode of glaciation. 13.4 13.5 13.6 Turn left (north) onto Gilder Court and ascend the crest of the moraine. Note the large glacial erratics in many front yards. Turn right (east) onto Tanager Lane. Turn left (north) onto Bobolink Lane. Bobolink crests the moraine and then descends steeply behind it. As we loop through this development built along the moraine note the common large erratic boulders and abundant cobbles characteristic of the capping till. 14.2 14.4 15.3 Turn left (east) onto Sandpiper Lane. As Sandpiper descends into a valley, note the presence of small kettle depressions in the front yards of several homes. Turn left (north) onto Old Bridge Road, a tunnel valley that ascends to the crest of the moraine to the south. Note the characteristic steep valley walls along both sides of the road. Turn left (north) onto Bread and Cheese Hollow Road. Like Stony Hollow, Bread and Cheese Hollow is a major north-south trending tunnel valley that breaches the crest of the moraine to form a shallow outwash channel. The road hugs the west side of the valley and the east side is somewhat obscured by trees and houses. The unusual name of this valley comes from a story associated with Richard Smith, the founder of Smithtown, for which Bread and Cheese Hollow Road forms the western boundary. As legend has it, Smith made a deal in 1665 with the local tribe to purchase a parcel of land. The agreed terms were that Smith would take possession of all lands he could circle in a day, from sunup to sundown, riding on his trusty bull “Whisper”. Came the longest day of the year, Smith set out. At noon, he stopped to eat his lunch of bread and cheese in the eponymous hollow (Molly McCarthy, Long Island, Our Story). 16.2 17.2 18.1 18.9 19.5 Turn left (west) at intersection of Bread and Cheese Hollow with Route 25A. 25A meanders westward ascending and descending through a series of short valleys that may be segments of a continuous meltwater tunnel that was developed both within and below the base of the glacier. Pass Rinaldo Road to the left (north), a short, steep-sided tunnel valley. Turn right (south) at intersection of Waterside Road and Route 25A. Waterside Road is yet another example of a deep, narrow tunnel valley. Public supply well on right (east) side of road. Seaside Court and Waterside Road. Stop and park. Walk south on Waterside Avenue to trail entrance to wooded area on east side. Stop 2: Henry Ingraham Nature Preserve, Northport This wooded property was once part of an estate and preserves a good example of kame and kettle topography, which is characteristic of moraine deposits produced by the wasting away of ice during glacial retreat. Not far from the road the trail leads to a large, steep-sided, amphitheater-like depression in the side of the hill. A horseshoe-shaped pond occupies the bottom of the depression. This is a large kettle hole, produced when a block of ice became stranded during glacial retreat and partially buried in outwash and till. Following the path around the kettle leads to several smaller kettle depressions developed in the side of the knobby hills of the moraine, called kames. Kames are produced when deposits of sediment collect in depressions on the wasting glacier. As the ice sheet melts away completely the sediments are left stranded as small kame hills. Note the large, split erratic boulder adjacent to one of the smaller kettles. 19.7 Turn left (west) at the intersection of Waterside Road and Eatons Neck Road and ascend the moraine. 19.8 20.1 20.9 Entrance to the LIPA Northport generating station, a large, oil burning power plant whose four large smokestacks are a prominent feature of the north shore skyline. Turn left (south) onto Ocean Avenue. Turn right (west) onto James Street. Pull over at wide area on right side of road. Stop 3: Steer’s Pit Overlook James Street follows the south side of a large depression carved into the side of the moraine by sand mining. Mining operations began in 1923 and ended in the 1950’s when residents forced the pit to close because it was encroaching on Ocean Avenue. Subsequently, the land within the former sand mine was developed into housing and condos. From the vantage point at the top of the pit one can see Northport Bay, which is bordered on the north by a tombolo called Ashroken connecting Northport to Eatons Neck. In the distance can be seen Long Island Sound and the Connecticut shoreline. 21.1 21.9 Left onto Northwest Drive, left onto Lewis Avenue, looping back to Ocean Avenue. Continue south on Ocean Avenue. Turn right (west) at intersection of Ocean Avenue and Main Street. Main Street in Northport Village is an excellent example of a short, steep tunnel valley. The businesses along Main Street occupy the bottom of the valley and steep valley walls rise on both sides. At the end of Main Street is Northport Harbor, which itself is a northward extension of the Stony Hollow tunnel valley. Northport was originally called Opcathontyche (“wading place creek”) by the Matinecocks who lived there. It was settled by farmers in the mid-1600’s who cleared the surrounding land and raised cattle, giving the town its original name, Great Cow Harbor. The name Northport first appears in town records in 1837, although it is not known why the new name was chosen. In the 1800’s Northport was a major shipbuilding port, with shipyards springing up along Bayview Avenue during the War of 1812 (Bill Bleyer, Long Island, Our Story). 22.4 23.1 Turn left (south) at intersection of Woodbine Avenue and Main Street. Woodbine follows the steep slope on the east side of the harbor. Turn right (west) at intersection of Woodbine Avenue and Route 25A. Return west to Huntington on 25A. Optional Stop 4: Centerport Harbor at Mill Dam Road Turn right (north) at Little Neck Road in Centerport and bear left onto Prospect Road. Turn left onto Mill Dam Road and cross the harbor. Park at the pull off at the west end of Mill Dam Road. This stop affords a view of the harbor to the north and the gap in the moraine to the south created by the Stony Hollow tunnel valley. Acknowledgements I thank Gail Bennington, Cheryl Zorn, and Brian Antonio for their help mapping out the field trip route. Robert Peterson graciously permitted access to his property at the Steer’s Pit overlook. References AIA Architectural Guide to Nassau and Suffolk Counties, Long Island, 1992, Dover Publications Inc., New York, 205 p. Long Island, Our Story web site, http://www.lihistory.com/