One-eyed pinhead regulates cell motility independent of Squint/Cyclops signaling

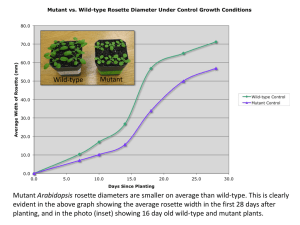

advertisement