Using Authentic Materials in an ABE Writing Class fall 2004

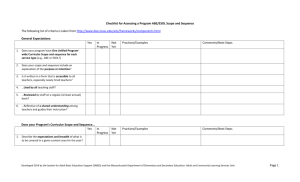

advertisement