Beyond Apartheid: South Africa’s Long Journey

advertisement

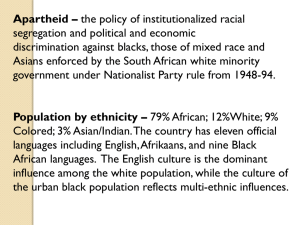

Global Studies Name _________________________________________ Beyond Apartheid: South Africa’s Long Journey Introduction 1. How is South Africa feeling about its future? 2. What problems has South Africa experienced over the past year? 3. What longtime problems does South Africa face? 4. What do you think “white flight” means? A ‘Young, Messy’ Democracy 5. What was apartheid? 6. What example of international pressure to end apartheid does the article give? 7. What happened in 1990? 8. What happened in 1994? 9. What did some fear would happen after the 1994 election? After Mandela 10. Who assumed the presidency after Mandela? 11. What was this president criticized for? 12. How did he leave office? 13. Who was expected to assume the presidency next? (He did!) 14. What has happened to the white population since 1996? 15. What countries do some fear South Africa will become like? 16. What political party rules South Africa? ‘Don’t Panic’ 17. What are some of the reasons for optimism in South Africa? 18. Why can the exit of President Mbeki be viewed positively? 19. What South African strengths does financial advisor Louis Fourie point out? 20. What chances does businessman and author Alan Knott-Craig give South Africa of still being a viable country in 20202? Beyond Apartheid: South Africa's Long Journey It's still a bright spot on a troubled continent. But South Africa is facing tough realities 14 years after the start of majority rule. By Barry Bearak in Diepsloot, New York Times Upfront Magazine, November 3, 2008 A dusty maze of concrete, sheet metal, and scrap wood, Diepsloot is like many of the enormous settlements around Johannesburg: mile after mile of feebly assembled shacks, an impromptu patchwork of the poor, the extremely poor, and the hopelessly poor. Monica Xangathi, 40, lives here in a shanty she shares with her brother's family. "This is not the way I thought my life would turn out," she says. Her disappointment is not only with herself, but with her country. Fourteen years after the end of apartheid, South Africa—the global pariah that became a global inspiration—is feeling gloomy and anxious about its future. "If only I could make Nelson Mandela come back," Xangathi says of the man, now 90 years old, who led the struggle against apartheid and became the country's first democratically elected President in 1994. "If only I could feed him a potion and make him young again." This longing for the past is rooted in more than nostalgia. The past year has been especially unnerving for South Africans, with one bleak event after another in a country long considered an example of progress. Economic growth has slowed; prices have shot up. Riots have broken out in several cities, with mobs killing dozens of impoverished foreigners, many from neighboring Zimbabwe, and chasing thousands more from their meager homes. A vicious power struggle recently ousted the President and has added political turmoil to the mix. And longtime problems continue to pose enormous challenges, starting with AIDS: About 20 percent of adults, almost 6 million people, have HIV/AIDS, which accounts for half the country's deaths. South Africa also has one of the highest crime rates in the world, and it's a major reason for the increasing "white flight" that is robbing the economy of many of its professionals. But just as alarming as the quantity of lawbreaking is the cruelty. Robberies are often accompanied by appalling violence, and people here one-up each other with tales of scalding and shooting and slicing and garroting. In defense, the poor apply padlocks. The rich surround their homes with concrete and barbed wire—and there are signs that more are simply fleeing the country. "On our street alone, just that one small street, three of the husbands in families were killed in carjackings or robberies," says Antony McKechnie, an electrical engineer who moved to New Zealand over the summer. "If we had stayed and something had happened to any of our three children, we would never be able to forgive ourselves." A 'Young, Messy' Democracy The complaints of rich and poor, black, white, and mixed race may differ, but the discontent is shared. Polls show a pervasive distrust of government, political parties, and the police. For much of the 20th century, a white minority ruled South Africa under apartheid, a government-run system that segregated blacks from whites and denied blacks basic rights. Apartheid essentially treated nonwhites as aliens in their own land. But by the late 1980s, the South African government came under increasing pressure to dismantle apartheid. Many countries, including the United States, imposed economic sanctions on South Africa to pressure it to change. In 1990, the government legalized black political groups like the African National Congress; freed Mandela, its leader, after 27 years in prison; and began negotiations toward majority rule. In 1994, blacks and whites went to the polls to elect a new government in one of the 20th century's most inspiring civic exercises. Some feared a racial bloodbath when white rule ended, with blacks taking revenge for past deprivations and injustices. Instead, South Africans embraced their new political power, with nearly 90 percent of those eligible casting ballots. Mandela was elected President. But in the years since, the optimism of those early days of democracy has been replaced by the tough reality of South Africa's many challenges. "We are not the world's greatest fairy tale, but rather a young, messy, and not-alwayspredictable democracy," says South African journalist Mark Gevisser. After Mandela Thabo Mbeki, who succeeded Mandela in 1999, was President for nine years. His presidency was sharply criticized for his failure to act on two fronts: the AIDS crisis and deteriorating conditions in neighboring Zimbabwe. Mbeki has expressed doubts about whether HIV causes AIDS, and resisted the distribution of drugs that could have treated millions. And critics say Mbeki did little to use South Africa's influence against the ruinous rule in Zimbabwe of Robert Mugabe. Mbeki's own party, the ruling A.N.C., forced him out of office in September, installing Kgalema Motlanthe as interim President. After next year's parliamentary election, Mbeki's longtime rival Jacob Zuma is expected to assume the presidency. The onslaught of unsettling news has proved too much for many people with the means to flee. Since 1996, the black population has risen to 38.5 million from 31.8 million, according to government statistics, while the white population has dropped to 4.5 million from 4.8 million. John Loos, an economist at First National Bank of South Africa who tracks the reasons given by home sellers in white suburban markets, says that in the last quarter of 2007, 9 percent said that they were leaving the country. In the first quarter of 2008, the number rose to 12 percent; in the second quarter it reached 18 percent. Some whites and other minority groups have reacted particularly strongly to the country's current problems, Loos says, adding, "We have people with the mind-set that this country is just another Zimbabwe in the making." Far fewer blacks emigrate out of such despair, but that does not mean they are more optimistic. "Things are quite scary here," says Rodney Muzuli, a community development worker. "You wonder if we're going the path of Rwanda" where tensions between ethnic groups escalated into genocide in 1994. Louis Manjanja, 26, a TV installer, blames the African National Congress for the troubles. "The A.N.C. is a bunch of greedy guys fighting for positions and ignoring what needs to be done," he says. "I voted for them before, but not again." 'Don't Panic!' Even amid the turmoil, there are reasons for optimism: The situation of the poor is improving: The unemployment rate, however high, is declining; the incomes of the poor, however meager, are on the rise. Political analyst Adam Habib even sees a silver lining in the recent political tumult: Mbeki's exit from the presidency was, in fact, a smooth and nonviolent transfer of power—something quite rare in Africa. "Our democracy is only 14 years old," Habib says. "Rather than calling this a crisis, people ought to ask how our institutions came together so well in so short a time." Indeed, South African pessimism has spawned a countervailing industry of reassurance. Louis Fourie, a financial adviser, travels the country delivering a speech called "South Africa, How Are You?" Yes, he confesses, the public-education system is deplorable. Yes, crime is horrendous. Yes, 20 million impoverished South Africans are "living in hell, no other way to describe it." But Fourie notes that the country has 1,500 miles of gorgeous coastline, 10 international airports, a well-managed stock exchange, and an open society with a free press. He fondly repeats the phrase that South Africa is "the most unsung success story in modern history." Since May, one of the nation's best-selling books has been a pep talk titled Don't Panic! by a businessman, Alan Knott-Craig. Aimed primarily at downhearted white South Africans, the book laments the "tsunami of negativity" and discourages those who are considering emigration. But even Knott-Craig is susceptible to gloom. "Will we still have a viable country in 2020?" he asks rhetorically in his book's preface. His cautious answer is revealing: "I think we've got a better than 50-50 chance."