Constituency Cleavages and Congressional Parties

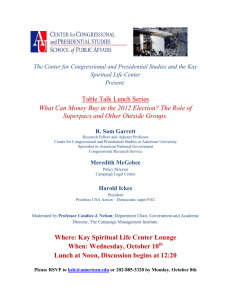

advertisement