“Unleashing” or Harnessing “Armies of Compassion”?: Some Questions about the

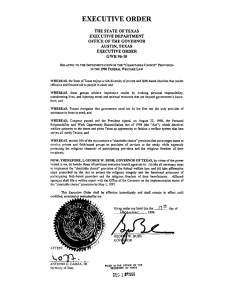

advertisement