Division of attention: Age differences

advertisement

Memory & Cognition

t984, 12 (6), 613-620

Division of attention: Age differences

on a visually presentedmemory task

TIMOTHY A. SALTHOUSE. JANICE DAVENPORT ROGAN. And KENNETH A. PRILL

IJniversity

of Missouri,Columbia,Missouri

.

I

I

I

I

Young and old adults were comparedin their efficiency of remembering concurrently presented

seriesofletters and digits in three separateexperiments.Instructions and payoffsto vary attentional emphasis acrossthe two types of material in different conditions allowed the examination

ofattention-operating characteristics in the two age groups. Strategy-independent measures derived from these attention-operatingcharacteristicsrevealedthat older adults exhibited greater

performance deficits than young adults when dividing their attention between the two tasks,

even though dual-task difficulty was individually adjusted for each subject.It was concludedthat

either the total amount of attention available for distribution or the efficiency of its allocation

decreasedwith age even though the ability to vary one's attention between concurrent tasks in

responseto instructions and payoffs remained intact.

Difficulties in dividing one's attentionacrosstwo or

more activities have beenpostulatedto be responsiblefor

many of the perceptual, cognitive, and motor deficiencies observedwith increasedage. For example,Wright

(1981)assertedthat "one of the most replicablefindings

about short-termmemory changeswith increasingage is

that older adults' performanceis affected more adversely

by divided attention conditions than is that of younger

adults" (p. 605). Burke and Light (1981) and Craik

(197'l) have drawn similar conclusionsbasedon extensive reviews of the literatureon memory and aging. Indeed,severalstudies(e.g., Caird, 1966;Inglis & Ankus,

1965; Inglis & Caird, 1963; Parkinson, Lindholm, &

Urell, 1980)have reported that older adults generally exhibit greater performanceimpairmentsthan young adults

when required to divide their attention betweentwo concurrent tasks in dichotic-listeningsituations.

However, we believethat at leastthreeproblemshamper the interpretation of these divided-attention studies:

lack of control over the individual's relative emphasison

one task or the other, unknown resourcerequirementsfor

each task, and uncontrolled age differences on each task

when performed in isolation. With respect to the first

problem, one cannothope to quantify the dual-taskdecrement if the magnitude of the decrement varies with

differential emphasis on the two tasks; for example, a

small decrement might result with heavy emphasis on

Task I and light emphasison Task 2, but a large decrement might be obtainedwhen the tasksreceive equal emphasis.The secondproblem relatesto the fact that Task I

This research was supported by a Research Council grant from the

GraduateSchool, University ofMissouri, and ResearchCareer Development Award N.I.A. I K04 AG00I46-01A1 to T.A.S. We would like

to thank the anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestionson an earlier

draft of this article. Please address reprint requests to T. Salthouse,

Department of Psychology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO

65211.

may require, say, 5% of the total attentionalcapacityto

producea unit increasein performance,whereasTask 2

may require orlJyl% of the capacity to achievecomparable performance improvement. Because performance

generally varies across individuals on both concurrent

tasks, only qualitative comparisonsof the severity of

divided-attention impairment have been possible in the

earlier studies.

With respectto the third problem, the addedcomplexity posedby the division of attention may have different

effectsdependingupon the proficiency with which the subjects handlethe tasksin single, focused-attention,

conditions. If different individuals perform at varying levels

in single-taskconditions, it is likely that they differ in the

proportion by which task difficulty is increasedby the requirementof having to perform two taskssimultaneously.

As a consequence,many divided-attention comparisons

in the past may have been confounded with overall level

of difficulty such that the poorer-performing individuals

in the single task experienceda greater increment in overall difficulty in the divided-attention conditions than the

better-performing individuals becausethey were already

operating closer to their performance limits.

The first two of these problems seem resolvable with

a modification of a procedure introduced by Kinchla

(1980)and Sperling(1978; Sperling& Melchner, 1978).

Their method is to obtain data across several dual-task

conditions, with each condition involving different relative emphases on the two tasks. In this manner, an

attention-operating characteristic (AOC) can be constructed in which performance on Task I is represented

along the ordinate and performance on Task 2 is

representedalong the abscissa.A given point on the AOC

signihesa particular combinationof Task I emphasisand

Task 2 emphasis,but the complete function indicatesthe

overall, emphasis-independent,divided-attention effect.

Moreover. becausethe axesof the AOC are scaledin units

of performance on each task, one can directly compare

613

Copyright 1985 PsychonomicSociety, Inc.

614

SALTHOUSE,ROGAN, AND PRILL

the effects of performance change in Task

I in units of

Task 2, thereby solving theproblEm ofunkno*n

resource

requirements.

Our modification to the AOC procedure is to

use the

area above the AOC as a measure of divided_attention

attentiontask was to rememberas many items

as possi_

ble from the two channelswhen they *"i"

f..r"nt"O .on_

presentingthe stimuti one pair ar a

:lli.",lf

.j"stld q{

ttme, all the

stimuli were presentedsimultaneouslyto

facilitate resourceallocation acrosschannels;

Gut ir, m.r"

Sarthouse,

re82).rhe reasoningshouldhavebeenmore leeway

:::::J:1.

:"T?:..e.a

for participantsioOistrib_

rs rnat pertect division of attentionwould be

manifestei ute their attentionthan with paced

siquential presentation.

c.onsistingof a single point correspondingro

A.limited presentationtime (3 ,..) *u, employed

ll^"1_loc

the lntersectionof the lines representingmaximu.

to

minimize organizarional factors that might f,uri

i.riJJt"J

formance on eachtask. This puit".n *ouid ,ho*

that per_ in the transfer of information into

toni+erm memory.

formance on each task is unaffectedby Oemanas

for per_

To someresearchers,it might ,".rn i.unga to use

formance on the other. Such an eOi would

the

"divided

encompass term

attention" in the presentconiext. Our ar_

the entire area ofthe dual-taskspace,and

thereforethe

gument.forthe presentusageis is follows:

Somethingis

divided-attentioncost would be b. Less+han_maximum

responsiblefor effective performance on both single

ind

performance on one or both tasks would result

in AOCs

dual tasks;that somethinghasclear limitations in

ti'at per_

below and to the left of the optimum point,

and thus the

formancecannotbe infinitely increased;and whatever

it

area above the AOC can be interpreteh as a reflection

of

is.caneasily be allocatedo, diuidedacrossdistinct

tasks.

the costs of divided attention.

Theseare all characteristicscommonly anributed

to the

The problem ofuncontrolled age differences in

single_ conceptofattention, and the fact that

tire taskshad a du_

task conditions of dichoticJistening experiments

was dis_ ration of 3 sec meansmerely,that there

was ample time

cussedby Parkinsonet al. (19g0), who pointed

out that

for the operationof all relevanrprocesses.It is true

that

many studiesreported trends for older indlividuals

to have thesecharacteristicsalso apply to structural

concepts

such

smaller

spans

than their young counterparts. In

T"--9ry

as memory capacityor the numb€r of slots available

in

a study of their own, parkinson et al. fo-undthat

dichotic_ some finite. storage system. and the

present research

listening differencesbetween their youn!

unO ota ug"

results might as easily be interpreted;ith a structural

groups disappearedwhen subjectswere mitched

on difit

m:qphor. However, becauseof our interestin the process

"b"

span and screenedfor h_ea_ring

deficits. Thus, it rnuy

of alteringemphasisfrom one task ro another.and

in inthat slightperformance differencesare enlarged

when the

terpretingthe resultingfunctionsas reflecrionsof differen_

number of mental operationsrequired to periorm

the task

tral allocationof a flexible_capaciq.u.eprefer a more

dy_

is increased, as is certainly the case when two tasks

are

namicconceptualization

of resourie limitarionsto account

performed concurrentlv.

for the findings.

An even more impreisive demonstrationof the

impor_

tance of controlling for single_taskperformance

when

making comparisonsin dual-tasksituationswas

EXPERIME\T

I

evident

in a recent experimentby Sombergand Salthouse(lgg2).

Method

Here, the samepattern of attentio=n

allocation was found

Subjects.

Twenty-four

ln young and old adults with two concurrent perceptual

collegestudenrs

I meanase= | E.9r ears,

range=l8 to 22years)

and24olderadulrs

rmean

discriminationtasksafter stimulusdurationsweie

ole=69 5 1ears.

adjusted *".9:=.5?,982.years)

participared

in a srngle

.e.ion nf approxi_

yr,"tgequivalentperformanceacrossagegroups

mately 1.5 h. There were ll males and l-1

in the

1-"

iemalcs In each group.

slngle-taskconditions.Theseresultsarelspeciaily

con_ l^.-:lT,"l finding in rhe psychologrcal trrerarure on'agrng rs that

vincing becausethe equatingtechniqueuuold"a ..select lncreased age rs associated with poorer perlbrmant-e on

speeded

measures, but is either unrelated to or gr.srtrrelr

gloup" interpretations that might beapplied to the par_

correlated nrth

abitity..

The preseni sampte of sublecrs *ere

kinson etal. (1980) result deJcribeaabove. Similarly,

T:1:T1"f,_y.rbal

conslsrent

wlth these trends in that rhe rcxrng sub.Jects

irad hrgher

although the two groups were identical in their dual_task scores on

the s@-based Wechsler .lOuh lnreihgence

Sca.le(WAIS)

performance, they still exhibited typical age trends

digit symbolsubstitution

in the

test.[65 2 r, .r: i,-ii+Or=-A.tS,

p .

duration required for a fix-edlevel ofpe.ceptual accuracy .00011,

but lowerscoreson rhl Nelson-Denny

normC Vocabu_

laryTest[20.8vs. 23.1;t(4g;=2 93.p < .05f m. i"n", perhaps

with each component task. The uppu..nti.plication

,

is

duein,partto a greateraverage

that age differences found in othei studies may

numberof yearsof education

in

not be

theoldersampte

,rGr=i.zo,ii.".doo]f . Thecur[16.4vs.13.4':

solely attributable to the unique requirements of having

rent samplescan therefore be consideredrepresentative

of their

to divide one's attentionbetweentwo concurrentactivities. respectrve

populations,at leastin termsofthe abovemeasures.

InIt secmeddesirable to extend the Somberg and Salthouse deed, if anything, the older

were superior

to the young

'

subjectson the dimensionof-subjgcts

(1982) procedure to a more demandingrn"rnory

veibal ability.

task that

Apparatus. Stimuli were presentedon a computer-controlled

might be expectedto involve greater atounts of pro".rr_

monirorposirionedin fronr ofthe seatedsublect.A

ing over.a longer period of time than the percepiual

dis_ l:lil9i:pl"y

laDoratory

computerwasusedto generaterandomlyorderedseries

crimination task. The presentexperimentstherifore

em_ of letters (all consonants)and dilits (0_9)and to i..oiO and ana_

ployed a vlsual concurrent-memorytask with two

lyze responses.

distinct

Procedure. The subjectswere first given instructionsatrrur

setsof material, eachconstitutinga ..channel." One

rhe

set general

natureof the task, and memory spanfor both drsrr: and

of material consistedof letters and the other of digits

to

A list of materiaiconsirrea.tli;.;;;l

facilitate "channel" categorization, and the divided_ letterswas thenassessed.

column of randomlygenerateditems with the con\rrarnl

lhtrt rhe

I

I

t

r

I

DIVIDED ATTENTION

same item could not occur in consecutive positions. A trial cons i s t e do f p r e s e n t a t i o n o f t h e l i s t f o r I t e c , i f t e r w h i c h t h e s u b j e c t

attempted to orally reproduce the items in their proper (top-tobonom) sequence.The responseswere keyed into the computer by

the experimenter, and a correct trial was defined as all items being

rcported in the correct sequence.The number of items started with

three and was increased by one with two correct reproductions of

the sequenceuntil four of five trials were incorrect, at which time

the span was identified as the previous sequencelength. The maximum sequencelength correctly reproduced in each oftwo separate

trials therefore defined the span. Two blocks of letters and two

blocks ofdigits were presentedin a counterbalancedorder, and the

averageof the two assessmentsserved as the memory span for each

type of material.

I n t h e d u a l - t a s kt r i a l s , b o t h a s e r i e so f d i g i t s a n d a s e r i e so f l e t ters were presented simultaneously for 3 sec, with subjects being

required to respond, again orally, to both. The two setsofmaterial

were arranged in two columns horizontally separatedby approximately 5'of visual angle, with the material to be reported first always on the left. The number of items presented in the dual-task

conditions was 75% (truncated to the nearest integer) of the individual's span length for each type of material, that is, 75% span

length of digits and'15% span length of letters, yielding a total of

I 50 % of the average of the spans for the two setsof material. (The

150% value was chosen to ensure that the composite task requirements exceededa subject's capacity, but was not so overwhelming

that it made the task too frustrating.)

Five experimental conditions were distinguished by the emphasis (manipulated by payoffs of 0Q to 40 per correct response)the

subjects were to give to each of the two memory tasks: 0/4, l/3,

212,311, and 4/0. Responseswere always required to both series,

but in the 0/4 and 4/0 emphasisconditions, random guessesfor the

unattended series would have been sufficient.

Therc were two blocks of trials, with each block containins five

subblocks of l0 trials for each emphasis condition. The orJer of

emphasisconditions (Ol4 to 4lO vs. 4/0 to 0/4) was counterbalanced

across subjects. One-half of the subjects reported digits first and

letters second for the first block, and the reverse for the second

block. The remaining subjects reported letters first and digits second in the first block, and the opposite in the second block.

Results

The young adultshad slightly higher letter spans[5.88

v s . 5 . 5 2 ; t ( 4 6 ) : 1 . 6 9 1 a n d d i g i t s p a n sU . 2 7 v s . 6 . 9 6 ;

(40) = l. l6l thanthe older adults,but the differencewas

not significantwith either type of material. The percentagesof correct responsesin the dual-taskconditions were

subjectedto a2 (age)x2 (material)x2 (order)x5 (emphasis)analysisof variance.Age was a between-groups

variable, and all other variableswere within groups. Two

additional analyseswere also conducted. In one, the

criterion for scoringrecall attemptswas relaxedto count

an item as correct whetheror not it was in the proper serial

position. This "free-recall" analysisyielded resultsnearly

identical to those reported below, but with a slightly

smallerorder effect due to the secondorder's benefiting

more from the relaxedcriterion. In anotheranalysis,the

possibilityof differencesbetweenthe trial-block sequences

(i.e., performanceon the first trial block vs. performance

on the second)was examined,but no main effectsor interactionswere found, so that datawere collapsedacross

this variable.

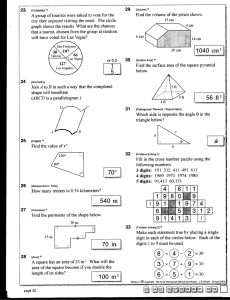

All the main effectsin the initial analysiswere significant: age-older individualsperformedat a lower over-

6I5

all levelthanyoungindividuals[F(l,46):5.35, p < .05];

material-letters were more difficult to recall than digits

lF(I,46):12.65. p < .0011;order-the secondseries

reportedgave the subjectsmore difficulty than the first

series [F(1,461:274.t0, p < .0001]; and, finally,

emphasis-the subjectswere able to shift their attention

from one task to the other [F(4,184):520.72, p <

.00011.The agedifferencesmust be qualified, however,

by the presenceof a significantage x order interaction

in Figure 1, both

lF(I,46):5. 12,p < .051.As illustrated

agegroupswere worse at recallingthe secondseries,but

the decreasein performancewas greaterfor the older individuals. It also can be seenby the parallel curves that

both agegroupswere comparablein their abilitiesto shift

attentionfrom one task to the other; similarity in the trends

for both age groupsis also indicatedby the lack ofa significant age x emphasisinteraction.Only two other interactions were significant: order X emphasis

of moreexrreme

lF(4,184):159.26,p < .00011,because

scoresfor the first seriesrecalledat both low and high

emphasis conditions, and material x emphasis

scores

lF(4, 184): 4.16, p < .0051,becauselow-emphasis

tendedto drop lower for letters than for digits.

Becausethe interactionbetweenageand order was significant, a closerexaminationof the differenceswas made

by separateanalyseson eachorder. The slight difference

in favor of young adultson the first set recalledwas not

significant,and no differencewas found with respectto

materialon this set. The subjectsdid alter their attentional

emphasison the first-recalledmaterial, however, because

the emphasismain effect was significant [F(4,184) :

6 2 1 . 6 8p

, <.00011.

Performanceof young and old adultsdivergedsignificantlyon the secondseriesreported[F(1,46):6.90, p <

.051.The materialmain effect was also significantin the

lI

o

o

o 6 0

o

o

G

c

o

9 4 0

o

o-

tsl

Recalled

t

t

t

I

L

0

I

I

1

L

L

2

i

3

,

4

EmphasisCondition

Figure l. Percentage correct across emphasis conditions for tasks

recalled first and tasks recalled second, collapsed across type of

material, Experiment l. A given point represents the average of96{)

trials (20 observations for each of 24 subjects for both letter and

digit material). The emphasis conditions are designated in terms of

the payoff received for correct performance with that set of material.

616

SALTHOUSE,ROGAN, AND PRILL

secondseries[F(1,46): 11.40,p < .005], reflectingthe

fact that letters were more difficult than digits when they

were reported second.The emphasismain effect continued

to be significantin the secondseries[F(4,184):182.68,

p < .00011,as was an age x emphasisinteraction resulting from the elderly group's lower performance on all

but the lowest emphasisconditions in the material reported

second[F(4,184):3.28, p < .05].

It is interesting to note that performance was above

chance(i.e., l0% for digits and 5% for letters) even in

the O-emphasisconditions. This appearedto be attributable to a tendencyamong many subjectsto remember the

first or the last item of the unattended(nonemphasized)

set, in addition to as many items as possible from the attended set.

Divided-attention cost was first computed for each individual in a dual-task space with coordinates ranging

from0% to IOO%on eachtask axis. The mean dividedattention cost regions, that is, the areas above the AOCs

(seeFigure 2), were .320 for young adultsand .388 for

older adults It(461:2.46, p < .051.

Relative divided-attention cost was also computed on

the basis of each individual's functional performance

region (Somberg& Salthouse,1982). In this analysis,the

dual-task spaceis restricted to the region defined by the

minimum and maximum performance levels actually obtained on each task, rather than by theoretical limits of

O% and 100%, thus taking into considerationeach individual's actual range of performance. Age-related decrements in performance comparableto those obtained with

the absolute divided-attention cost measurewere observed

with theserelative measureslt(461-2.69, p < .051,with

means of .270 for young and .355 for old.

o

o

o

@ o

o

u

4

u

3E

c

o

I

Q)

20

40

60

80

(Percenlage

Correct)

Letters

100

Figure 2. Empirically derivedattentionoperatingcharacteristics

(AOCs) for young and old adults, Experiment l Each point

representsperformance in one emphasiscondition (20 observations

for each of 24 subjects).For example,the point in the upper left

on both functions rrpresentsperformanceon the digit task (ordinate)

and the letter task (abscissa)when subjectswere instructed to place

lfi)7o emphasison the digits and 0Voemphasison the letters.

Discussion

Older adults were found to perform lesseffectively than

young adults across several different methods of measuring the divided-attentiondecrement.This finding may

have to be qualified somewhat,however, becauseit was

found that older adults performed nearly as well as young

adults on the first set recalled, but the differencesbetween

groups becameapparenton the secondset recalled in the

form of an age main effect and an age x emphasisinteraction. Severaldichotic-listeningstudieshave reporteda

similar result(althoughalwaysat a single,unknown,emphasiscondition), and two common interpretationshave

beenthat older adults are more susceptibleto either spontaneousdecayof second-recalleditems during the interval when first-set items are being recalled, or to response

interference effects produced b1' the recall of first-set items

(Craik, 1977). If either of tlresemechanismswere responsible for the presentdivided-anentionresults,it could be

argued that structural. rather than capacity, limitations

(Salthouse,1982) were responsiblefor the presentage

differences.Experimens 2 arrd3'*'ere thereforedesigned

to allow theseinterpretationsto be directly investigated

and to determine whether thel could account for the

presentage differencesin divided-anentionability.

EXPERIMENT

2

Experiment 2 was similar to Experiment l, but only a

singleresponsewas requiredto eachsetof material.One

position in each iuray wils cued at the time of the response,

and the task was simply to identify the cued item. This

manipulation greatly reduced the responserequirements

of the task, and, therefore. if response interference or

spontaneousdecay is the primary mechanism responsible for age differencesin divided attention,the differences

should have been minimized or eliminated.

Method

Subjects.Sixteencollegesodents(meanage:18.6 years,

range= I 8 to 22years)andl6 olderadults(meanage: 70.I years,

range:60to E4years)participated

in a singlesession

of approximatelyI .5 h. Therewere5 malesand1l femalesin theyounggroup

and4 malesand12females

in theoldgroup.Meanyearsof education were13.4for theyoungand17.l for theold [t(30):5.29,

p < .0011.

Meanscores

on theWAISdigitsymboltestwere67.I

for theyoungand216.6

for theold [t(30):4.89,p < .001].In both

mqsures,thecurrentsamples

weresimilarto thoseof ExperimentI

with commonlyreportedtrends.Noneof the subandconsistent

jectshadparticipated

in the previousexperiment.

Procedure.Thegeneralprocedure,

apparatus,

andmostof the

l.

specificdetailswerethesameasthosedescribed

for Experiment

Therewerethreemajordifferences.

Thefirst differencewasthat,

in Experiment

2, eachsetofmaterialin bothsingle-anddual-task

involveda singleresponse,

ofthe identityof

conditions

consisting

theitemcuedby a setof questionmarksin thepositionoccupied

by thetargetin thestimulusarray.Theremainingitemsin thearraywereindicated

with dashes,

andbelowthearraywasthequestion "Which letter?"or "Which digit?" to remindthesubjectof

the materialhe or shewasto supplyby pressingtheappropriate

keyon thekeyboard.Thelocationofthe probein thestimulusar-

I

I

I

DIVIDED ATTENTION

I

ray wasvariedrandomlvacrosssequence

positionswith the re_

strictionthatontheaveriseeachporitlon

,uJuiJ[J p.j* "quurfy

often.A response

*u. ,"oiir"d roi.n..y

f.i!;"";; fiJity a

on.a givenbtockof duaj_msk

oiurr.iiJol"o-.;;,J*:l andsuess.

terter

probeswasconstant,

butthiso.0".,u. uulun"laii.ir", i.,ur

uro"t,

tor eachsubiect.

Theseconiprocedural

difference

fromthepreviousexperiment

initialsingle_rask

spans

werederermined

Ltt-rlS"

witha cnterion

ot tourcorrecrresponses

ourof five ir.rcu; ;;;;i; i*l outor rru.

to minimize

thecontribution-of

cnun.e*itr,;;lr?r;;;;

response

Thethird modification

of rn. pi.ui*.-.*pt irn"n, *u,

f.,jltl],

anrncrease

from l0 to 20 trialsperemphasis

.onAiiiin p". uro"t,

ror a totalof 200 trials.

Results

The age differences were significant

o

@<)

o g

5

o

q

o

o

in

: 6.56,old= 5.o: itro.l: j.ij,'fthe lener_span

task.

[young

;

. .0s1,uu,

ngt.illhl9igit-span

task[y^oung

= i .{s, ,tdJ .al; t(30)

j_,t.ol. Thepercentag.,

or.o.i..t ..;p";r;, inthedual_

task conditionswere subjected,o

un ug. x mate.lat x

order x emphasisanalyiis of variancE.

the'foilowing

main effects were signihcun,,

ug"_young'riU;""t, t uO

jaer

higher

(Percentagerscorrect)

Figure 4. Empiricallv_derived AOCs

for young and old adults,

Experiment 2. Each ooint represents

pe.forman"E in one emphasis

condition(40

observation.

ri. .""r,-Jiiffiil;;l

scores

rhan

subjeciifFiiJAj=;.21, p (

.0051;order-thetrrst,..ie, ,eported

r,ujiigr,". ,"or", similar age differences.on both orders

and the absence

lF(I,30): 26.20,p < .000rI ; ";J ;ilili;:rcor",

in_ of a significant interaction U"t*".n ug"lni order, sug_

creased

withanentionat

empirasis

fF(4,it6;=;60.90,p geststhat responseinterference effects i" l"r, pronounced

< .00011.

The only significantrnt;r;";i;;u,

than in Experiment -.

The AOCs derive_dfrom these data are illustrated

in

effects were more p.onoun""d-at higher

Figure 4. As implied by Figure 4,

;il;;"I,,

attentional emphases.

had a sig_

nificantty

The significantrrendsare illustrated

-highei absolute"divtd;:;;;

cosr than

.

in Figure 3. No_ young adults[.339 vs. .240; t(301:3.

16,

:

.005].

The

;

o.0.."n".t. ftiro.run." age differenceswere in the expecteddireciion

ll.,l1"l: g:rqitethesignificunt

but

did

not

marerial*u, rnu"t'.jorrr to that achievestatisticalsignificance

:1.I.j""-d-reported

*ith th";;;sure or.etu_

ur

urcrlrst_reponed

materialthanwasthecasein Experi_ tive divided-aftention

cost based on each individual,s

mentI (cf. Figurel). Thistrend,togetheiwitt

.ougtty functional performanceregion

[.3g2 "r. .:jO; (30) =

1.65,.15>p>.101.

emphasis

rr(qnq:i.t

1.9:I

i"9

tng that

the order

,oo

I

H' |

I

""

"" ":=t4"

,.;/4.;il_,*i

o"\1, od

' .

p*f

,/'

l

,.f i'..

r

!---

indicat__

r.,n"J[o I

I

8or

C I

? uolE

b",*""n

, ;'.'.i;i,

'./,,,'

/'/

I

l

I

I

I

r

'

Il

I

l

Discussion

The major findins of Experiment

2 was that the age

differences in dividid-aaention cost

were still evident

when the memory tasks are modified

to _inirr#" response

interference. However, the age

differences in the rela_

tive divided-attentioncost measure

were not "a

significant,

and the datain Fieure 3.indicatetfr",f,"i.

*",

tenOency,

atbeit not sratisd;atly signincanr,-foi'irJ

uJ."iin"r"n.",

to.be.morepronounced-o"rh; ;;;j;;"":iJ

It is thereforestill possible,o ".gu" ,hui-ril-"-ofmateriar.

the age

differencesin divided attention'fouiJi"

t_p"rfment I

wer^e_mediated

by greatersusceptibilityto ,.'spons.

in_

terlerence_or

spontaneous

decaywith in..easeaage.Ex_

periment3 wasconsequently

designeJio-p.oiia" uaai_

tional eviclencerelevant," ,f,t i"i".pr*,i"".

..*,*,*]I"Jlj*x"ir.r,asks

recattedfirsr and tasks recailed

;r;;,;;;;;.*s

ryp€ of

material, Experiment2. A civen po,n,

."p.ount".ti"lJera!e or r,Zm

trials (40 observationsfoieach'of

lo *ui*i.

i". tii*,etrer and

digif material). The emphasisconditions

are designared

in termsof

the payoff receivedfor cbrrcct p",f"r";;;;i'if;",'#ji,n","ri"r.

EXPERIMENT 3

In an aftemptto completelyeliminate

response

^

inter_

fglengeanddecayeffecti ro, p..fo.manl'in[J.

aiuia"a_

attentionconditions,thememory_span

taskswerefurther

modifiedin two respects.One."Ain""tio"

"Jnrirt"O of

618

't"t.'1,l

SALTHOUSE.ROGAN.AND PRILL

re-presentingall items in the array exceptthe cued item

at the time of response.It was believed that this would

reducethe necessityof cycling through one's memory to

locate the probe item at the time of recall, thereby

minimizing the possibilityof interferenceand shortening

the time to generatea response.The secondmodification

was to requesta responsefrom only one set of material

in the dual-taskconditions.That is, althoughboth letter

and digit arrays were always presented,on a given trial

the subjects were queried about only one (randomly

selected)array. Becauseonly a single item was to be

reported, there was no possibility of the recall of earlier

items interfering with the recall of subsequentitems, or

of information to be reportedseconddecayingduring the

reporting of information from the first series.

_=::qr_

8{J I

I

o

o

\il

6()

a

O

o

o__

{

I

lc

L- - l

'tu'"uT3fl5,.u"o""'t'

Method

Figure 5. Empiricalll derived AOCs for young and old adults,

Subjects.Sixteencollegestudents(meanage:19.1 years,

performance in one emphasis

(mean

range:18to22years)

age:66.6years, Experiment(303. Each point represents

and16olderadults

obsenations for each of 16 subjects).

range:62to 77 years)participated

ofapproxi- condition

in a singlesession

mately1.5h. Therewere6 malesand l0 females

in theyoung

group,and4 malesandl2 females

in theoldergroup.Meanyears Discussion

of education

were 13.6for the youngand l5.l for the old

The major finding of Erperiment 3 was that the age

were66.3

symbol

scores

It(30):1.63,.15> p > . l0l. Meandigit

in divided-attentioncost were replicatedin a

differences

p < .0001].These

for theyoungand42.9for theold[t1:O;=6.33,

results,

similarto thoseof Experiments

I and2, againsuggest

that task with virtually no opportunity for responseinterferpopula- encebecauseonly a singleresponsewas requiredon each

oftheir respective

the currentsampleswererepresentative

in eitherof the preced- trial. Moreover, in the presentexperiment,the agediffertions. Noneof the subjectshadparticipated

ing experiments.

enceswere significant in both the absoluteand relative

Procedure.Most of the proceduraldetailsweresimilarto those

measures

of divided-attention

cost.despitelower statistiThe major modificationswere:

of the precedingtwo experiments.

power

l. due to a smaller

cal

than

that

in

Experiment

addingthe identitiesof the noncueditemswhenpromptingfor the

numberofsubjectsper agegroup. It canthereforebe conrecall response;requestinga responsefrom only one of a trial's

two arraysin the dual-taskconditions;and increasingthe number cluded that the age differencesin divided-attentionabiloftrials per block to 150,for a total of 300 acrossthe two blocks,

ity with two concurrentmemon tasksare not attributafor the lossofdata from the second-reported ble simply to greater output interferenceon the part of

to partially comp€nsate

array. Determinationof which array to probeon a specificdualolder adults.

tasktrial was random,with the restrictionthat, on the average,the

letter and digit arrayswould receivean equal numberof probes

with eachattentional

emphasis.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

A primary focusof the presentexperimentswas the use

Results

The age differenceswere not statisticallysignificant of the AOC analysis,as first usedby Sombergand Salthouse(1982)with respectto divided attentionand aging,

with eitherthe digit-spantask [young : 8.16, old : 8.00;

tasks.

in relatively demandingconcurrent-memory-span

(30) < l.0l of the letter-spantask [young : 6.81, old

: 6.31; t(30) : 1.23, p > .501.The only significant Both the relative (Experiments I and 3) and absolute(Experimentsl-3) measuresof divided attentioncost indicated

effect in the analysis of variance on the percentagecorrect responsesin the dual-taskconditionswas emphasis that older adultswere more penalizedthan young adults

lF(4,120) :268.20, p < .00011.The ageeffectin per- by the divided-attention requirement, even after the

difficulty of the concurrenttaskswas adjustedto the same

centagecorrect in the dual-taskconditionswas in the exp e c t e dd i r e c t i o n( y o u n g : ' 7 0 . 1 % , o l d : 6 ' 7 . ? % ) , b u t proportional level for each individual subject.

Obtaining roughly equivalentagedifferencesin dividedfailed to reachan acceptablelevel ofstatistical significance

:

attention

costs across the three experimentsnot only

.

2

5

1

.

>

l

.

2

O

,

P

lF(1,30)

the reliability of the basicphenomenon,but

Despitethe similar overall level of performancein the demonstrates

also

suggests

that the locus ofthe age differenceis in the

revealed

an

age

deficit

two age groups, the AOCs still

initial stageof registrationor encodingof the informain divided-attention costs. The data are illustrated in

Figure 5, in which it can be seenthat older adults had tion. This inferenceis basedon the nearly identicalage

trends when the potential for storagedecay or response

higher divided-attentioncoststhan young adults[.218 vs.

were

interferencewas systematicallyreducedfrom Experiments

The

differences

age

.142; t(30):2.20, p < .051.

I to 2 to 3. Furthermore, the useof measuresderived from

measure

based

on

relative

cost

with

the

significant

also

individually determinedfunctional performanceregions AOCs, which representdual-taskperformanceacrossa

rangeof emphaseson the two tasks,indicatesthat the age

[ . 3 3 ] v s . . 1 9 9 ;t ( 3 0 ; : 2 . 6 1 , P < . 0 5 ] .

1

DIVIDED ATTENTION

I

differencesare not anributableto differential biases

or

strategiesfavoring one task over the other.

It thereforeseemsreasonableto concludethat the

age

differencesin the dual-taskconditionsare causedby

agi_

related limitations in successfully,

encodingitems when

two simultaneoussetsof material u.. p."rJnt"d. A

rela_

tively uninterestinginterpretationof this finding might

be

that it is causedby slower shiftsof fixation from one

task

(e.g., digits)to the other (e.g., lefters)in older

adultsthan

yo,ungadults. Although we cannot unequivocally

re_

in

ject this possibility. it is highly unlikely

that it could ac_

count for more than a small proportionof the age

differences.because

eye movementsof 5. (the spatiallsepara_

tion berween the arrays) typically'r"quir" less

than

a5

in young adults(Saitirour"& filir, 1980),and

31e.c

probably not much more in older adults. Atthese

rates,

a large number of redistributions of fixation could occur

within a very small fraction of the 3_secexposure

rime.

Our interpretationof the age differencesin the dual_

task conditionsis that they are causedby an age_related

reductionin a dynamic rather than a structura'lform

of

attentionalcapacity.This type of capacitymay simply be

equivalentto the rate of performing mlntal'operations

(Salthouse,1982), or it may be anal6gousto what

Craik

and Byrd (1982)termed..mentalene.gy... In eithercase,

however, the fact that fewer total itemi were reported in

the dual-taskconditionsthan the averageof the spansin

the single tasks (see Table l, as well is similar results

by Inglis & Ankus, 1965,and Inglis & Caird, 1963,with

dichotic listening tasks) suggestithat perfoimancewas

not limited by purely structuralfactors(e.g., number

of

slots). Instead,performanceappearsto bJrestricted by

more active processes,such as the initial allocation, or

subsequent

redistribution,coordination,and monitoring,

of capacity{emanding encodingoperationsacrossthe two

concurrenttask. Either the amountof the resourcesavailable for theseactivities or the efficiency with which they

are allocated to the various processing componentsap_

pears to decreasewith increasingage.

Despitelessefficient divided-atteniionperformancein

older adults than in young adults, the two age groups

.-c1rr'd I() allocateattentionacrossconditionsln

a simi_

hm of {reragettilt:t-t"lno Duat-Task

performance

loF

r-.:'.;:

Si:ic

l..r

i r:r:::e

Young

old

Average Number

of Items Recalled in

Dual-Task Conditions

Sl:: In

( ,:\:.!:,\n\

:l

l

n Ji

o:..

5 . 8I

5.25

Err-:-<:r l

Young

old

.

.rg

/-l-r

6.51

Expennr:r :

7.49

'7.16

6 -10

{

1 r

l r

6.{?

619

lar fashion,as indicatedby the comparabletrend of em_

phasisvariationsin all figures. This finding is important

in that it suggeststhat the ability to distribut-eone,i atten_

tion across two concurrent activities is relatively un_

affected by increasedage. There may be less attentional

capacityavailablefor distribution, or more overheadmay

be required to monitor the distribution of attention, but

the effectivenessof actualattentionallocationamong con_

current activities does not seem to be reduced between

2O and70 yearsofage. In this respect,then, characteriz_

ing the difficulty simply as poo.e. division of attention

may be misleading becauseyoung and old adults appear

to be equally proficient in the aciual partitioning of

the

availableattentionacrosstasks in responseto tlie vary_

ing emphasisconditions.

Finding older adults to be more disadvantagedthan

young adults when required to divide their attenti,onis

in_

consistentwith Somberg_and

Salthouse's(19g2) finding

of no divided-attentiondifferencesacrossagegroupscom_

parable.tothose employed here. The appaien-tcontradic_

tion in the patternof resultsmay be attiibutableto differ_

encesin the complexity of the tasks employed in the two

studies.The Sombergand Salthouseexperimentusedtwo

perceptualdiscriminationtasksthat seemto have involved

minimal.processingof information, when processingof

information is definedas the hypothesizednurnberof men_

tal.operationsperformed. The discrimination task required

subjectsmerely to detect and respond to the presenceof

a target. When two discrimination tasks were performed

concurrently, the number of mental operationsincreased,

but the greater demandswere still apparently within the

capabilityof both age groups. The iurrent experiments

usedmemory-spantasksin which the individuil was re_

qrriredto identi$, remember,and then reproduceeither

all, or a specifiedmember, of a seriesof letiers and digits.

Perhapsbecauseofthis addedcomplexity, agediffereices

were evident in the costs of dividing ittention between

two concurrentactivities. In other words, the explana_

tion that may account for the apparent discrepaniy be_

tweenthe current findings and thoie of SombergandSalt_

"of

house is simply that the larger the number

mental

op-erationsto be performed, the larger is the absoluteage

differencebetweenyoung and older adults. Wright (l9g'i)

cameto a similar conclusionwhen older adultsperformed

worse than young adults on a complex singljtask, and

interpretationshave been presentJdpreviously

3nal_oqgus

by Salthouse(1982, in press).

To summarize, older adults are penalized more than

young adults by the requirement oldividing their atten_

tion betweentwo concurrent tasks even when-thedifficulty

of the dual-task situation is the same frxed percentageoi

single-task performance for each individual. Howdver,

because_an

earlier experiment with a simpler set of tasks

revealed no age differences in divided_aitentionabilitv.

and becausethe present AOC analysesrevealed similai

capabilitiesof dividing the availableattentionalresources,

we suspectthat the age-associated

problem is not due sim_

ply to allocationof attention to alternative..channels,'

620

SALTHOUSE,ROGAN, AND PRILL

but, rather, is a problem in dealing with increasedcomplexity of the total situation. Age differences may be

present whenever composite task difficulty or demands

upon processingcapacity are great, and although dividedattention tasksoften involve high levels of difficulty, they

do not necessarilydo so, and there are many single-task

situations in which the level of task difficulty is high. Future research systematically analyzing the effects of additional mental operations (task difficulty) on the singletask and divided-attention performance of adults of varying ages would be desirable.

REFERENCES

Therole

andaging:

Bunxn,D. M., a LrcHt,L. L. (1981).

Memory

of retrieval processes. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 5 l3-546.

CerRD,W. K. (1966). Aging and short-term memory. Joumal of Gerontolosy, 21, 295-299.

CnrIx, F. I. M. (1977). Age differencesin human memory. In J. E.

Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Cnerx, F. I. M., e Byno, M. (1982).Aging and cognitivedeficits:The

rate of attentionalresources.In F. I. M. Craik & S. Trehub (Eds.),

Aging and cognitive processes. New York: Plenum.

Iuclrs, J., a ANxus, M. N. (1965). Effects of age on short-term storage

and serial rote learning. British J ourrnl of Psychology, 56, I 83- 195.

and serial rote learning. British Journal of Ps,v-chology,

56, I 83-195.

I N c L I S ,J . , a C e t n o , W . K . ( 1 9 6 3 ) . A g e d i f f e r e n c e si n s u c c e s s i v e

responsesto simultaneousstimulation. Canadian Journal of Psychology,17,98-105.

KrNcsr-e, R. A. (1980).The measurementof attention.ln R. S. Nickerson (Ed.), Attention and performance 12111.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

P a n x r n s o N ,S . R . , L r r . r o H o r - r Jr r., M . , a U n r u , T . ( 1 9 8 0 ) .A g i n g ,

dichotic memory, and digit span.Journal of Gerontology,35, 87-95.

SerrHousB, T. A. (1982). Adult cognition: An experimentalpsychology of human aging. New York: Springer-Verlag.

SrLtHousr, T. A. (in press). Speedof behavior and its implications

for cognition. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie(Eds.), Handbookof

the psychology of aging (2nd ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

S,rlrHouse, T. A., a Elr-rs, C. L. (1980). Determinantsof eye fixation duration. Ameican J ournal of Psychology, 93, 2O'7-234.

SowsBnc, B. L., a Selrsouse, T. A. (1982). Divided attentionabilities in young and old adults. Joumal of Experimental Psychology:

Human Perception ancl Performance, E, 651-663.

Snnnr-rNc,G. ( I 978). The attentionoperatingcharacteristic

: Examples

from visual search.Science,202, 315-318.

SesnLtNc, G., a MsI-cFrNBn,M. J. (1978). Visual search,visual attention, and the attention operating characteristic. In J. Requin (Ed.),

Attention and performance 211. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

WrucHr, R. E. (1981). Aging, divided attention,and processingcapacity. Journal of Gerontology,36, 605-614.

I

t

I

(Manuscript receivedJanuary 3, 1984;

revision accepted for publication August 2, 1984.)

I

t