Using Financial Innovation to Support Savers: From Coercion to Excitement

advertisement

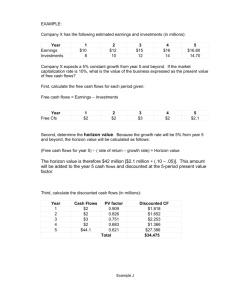

Using Financial Innovation to Support Savers: From Coercion to Excitement National Poverty Center Conference “Access, Assets, and Poverty” Peter Tufano Harvard Business School, D2D Fund, and NBER Daniel Schneider Princeton University Agenda Purpose of paper Categorizing savings levers The savings continuum The many unanswered questions Purpose of the paper Private savings—especially short term emergency savings—is a critical buffer for poor families Policy solutions often deal only with long-term retirement solutions, or propose expensive solutions. What is the menu of savings possibilities, supported by a combination of government, private sector, and NGOs? Not a relative evaluation—more to establish the landscape. What is the value of laying out the possibilities? People are different. Savings goals (retirement vs. emergency) Institutional settings (large employer vs. small/temporary employer) Mental makeup (right brain vs. left brain) Any one savings proposal—no matter how good-- cannot address all needs. Reframe the discussions more broadly, to bring in NGOs and private parties. Not everything requires change in law or big money. Along what dimensions do savings solutions differ? Degree of saver decision making None ÅÆ Complete Perceived barrier to savings Not enough resources to save Institutional impediments Individual inertia Perceived benefits of savings too small Savings “partner” Government, private sector, NGOs Economics to partner Expensive ÅÆ Profitable How can we support families? 1. Force them to save 2. Make it hard for them not to save 3. Make it easy for them to save 4. Bribe them to save 5. Social support for savings 6. Make them excited to save A continuum of savings levers Force to Save Hard Not to Save Easier to Save Bribe to Save Social Support Fun or Exciting Savings Current barrier All (ability and will) Saver's Role No choice Must refuse to save Given more opportunities, but must decide Likely partner Government Workplace, financial service vendors (Government OK) Retail sector, workplace, tax sites Government, Foundations Communities For profit financial service firms (Government OK) Cost or Profit Potential High cost (grants); medium cost (mandate) Generally low cost Medium cost (new channels); low cost (tax channel) High cost (matches, bonuses) Low $ cost; high effort by community Potential for profits Typical savings horizon Long horizon Varies Varies Long horizon Short horizon Short horizon Example Mandate (Social Security); Grant (Child Trust) Opt ins; Bundling; Commitment Products New distribution Channels; SMarT 401k, IDAs, Savers Credit ROSCAs Prize linked saving, collectible savings Institutional impediments, inertia Savings not "worth it"; Change savings equation Given different savings opportunities, but must decide 1. Forcing families to save Mandating savings Social Security system Granting savings U.K. Child Trust Fund All children born in UK post September 2002 Progressive grant at birth Investment choice with default option SEED demonstration and the ASPIRE Act Example: The UK Child Trust Fund Opportunity Performance 2.85 million accounts open as of June 2007 Approximately 25%- 30% of CTF accounts receiving regular deposits Provider and Cost Low-income children receive additional funds Large pre-program gap in savings for children by household income Public Sector £240 to £480 million annually Concerns Re-shuffling of assets Inter-cohort inequality Stake-blowing 2. Making it hard not to save Defaults 401(k) plans Pension reform Bundling Card-based savings programs Loan based program for bundled savings Bank of America “Keep the Change” debit card program UPromise Rewards Program North Carolina State Employees’ State Credit Union Making it hard to dis-save Commitment Savings products Example: 401(k) defaults Opportunity Performance Significant enrollment boost (up to 90% level) Disproportionate enrollment and balance benefit to low-income and racial/ethnic minority group members Provider and Cost Increase employee retirement savings Satisfy non discrimination test rules Employer provided Low/medium cost: compliance, additional match dollars Concerns Relatively low levels of plan access among LI families Default contribution rates and allocations are sticky Limited evidence on re-shuffling Example: The Salary Advance Loan Opportunity Performance $400 million in loans at maximum fee of $5 per loan $9.7 million in deposits 75% of SALO borrowers report that these funds are their first real savings Provider and Cost Reduce reliance on costly AFS loan products Help create savings for low-income families Private sector Low cost, profitable for the credit union Concerns Actually new savings? Sustainable on a broader scale by non-cooperative financial institutions? 3. Making it easy to save The Workplace SMarT Plan (Benartzi and Thaler, 2004) Tax Preparation Sites Refund-linked savings (Beverly, Schneider and Tufano, 2006) Schools Retail Point of Sale Example: Tax time savings Opportunity Performance Some demand for savings accounts at VITA sites (Beverly, Tescher, and Romich, 2004; Rhine, Su, Osaki, and Lee, 2005) H&R Block has opened 600,000 IRA and Savings accounts Refund Splitting may facilitate savings (Beverly, Schneider, and Tufano, 2007) Provider and Cost $110 Billion to families making less than $40,000 per year (2005) Average EITC refund of $1,900 Savable funds (Smeeding, Ross-Phillips, and O’Conner, 2000; Barrow and McGranaham, 2000; Barr and Dokko, 2006) Form 8888 Public Private Sector partnerships Small scale legislative/rule changes dramatically lower costs and allow for private sector innovation and involvement Concerns Point of sale access to savings products Universal savings product – US Savings Bonds? 4. “Bribing” people to save In general, the U.S. government spends $335 billion each year on promoting asset building (Woo, Schweke, and Bucholz, 2004)) Most in the form of tax subsidies Some support for low-income savers Mortgage tax deduction Retirement savings tax treatment Preferential capital gains rates Individual Development Accounts Saver’s Credit “Anti-Bribes” may discourage savings Example: Individual Development Accounts Opportunity Provider and Cost Federally financed, administered through financial institutions and small not-for-profit groups At scale, high cost Performance Encourage saving by low-income households Equalize governmental expenditures on asset-building incentives Mean (median) monthly saving in ADD of $19 ($10) (Schreiner et al, 2006) Higher savings among poorer participants in ADD Randomized experimental results show homeownership benefit for African Americans (Gale et al, 2006) Concerns Limited evidence of efficacy Current model of many small providers may not be scalable Stalled in Congress 5. Non-monetary incentives to save Savings is a “not” activity Group support helpful for “not” activities Weight Watchers AA Social networks can deplete financial resources or can help to build them. Rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) in South America, Asia, Africa, and immigrant communities in the US America Saves! in the United States Example: ROSCAs Opportunity Performance Widespread use in developing countries and in some immigrant enclaves in more developed countries Significant source of savings in many countries (Bouman, 1995) Provider and Cost Use social interaction to motivate savings (Biggart, 2001; Ambec and Treich, 2007) Manage family tensions over money (Anderson and Baland, 2002) Provide a means to establish social standing, engage in social relations, and build group cohesion (Ardner, 1964; Burman and Lembete, 1995; Gugertry, 2003) NGOs, community groups, informal networks Low dollar, but high social and time costs May be network enhancing Concerns Basic behavioral solution adaptable? Usefulness/efficacy in context of greater availability of formal financial services? 6. Making savings exciting Savings products where people save because they enjoy it? Prize-based savings Early use: Million Adventure (1694) in Great Britain Nineteenth Century: Most European governments (Levy-Ullmann, 1896) Twentieth Century: Brazil, United Arab Emirates, Ireland, Great Britain, Sweden, Pakistan , Pakistan Germany, Turkey, Kenya, Indonesia, Spain, Mexico, Argentina, Denmark, Oman, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, India, South Africa Collectible savings Example: FNB’s Million a Month Account Opportunity Provider and Cost Private sector product with public regulation Profit opportunity Performance Use new structure to motivate savings - 114 prizes awarded monthly, R1,000 to R1 Million Bring unbanked households into the formal South African financial system Contribute towards equalizing racial financial inequality Leverage public interest in gambling to increase savings 750,000 accounts opened over about 32 months R1.2 billion in deposits Concerns Lawsuit in South Africa, legally challenged in the United States May engender public opposition Summary: From coercion to excitement Force to Save Hard Not to Save Easier to Save Bribe to Save Social Support Fun or Exciting Savings Current barrier All (ability and will) Saver's Role No choice Must refuse to save Given more opportunities, but must decide Likely partner Government Workplace, financial service vendors (Government OK) Retail sector, workplace, tax sites Government, Foundations Communities For profit financial service firms (Government OK) Cost or Profit Potential High cost (grants); medium cost (mandate) Generally low cost Medium cost (new channels); low cost (tax channel) High cost (matches, bonuses) Low $ cost; high effort by community Potential for profits Typical savings horizon Long horizon Varies Varies Long horizon Short horizon Short horizon Example Mandate (Social Security); Grant (Child Trust) Opt ins; Bundling; Commitment Products New distribution Channels; SMarT 401k, IDAs, Savers Credit ROSCAs Prize linked saving, collectible savings Institutional impediments, inertia Savings not "worth it"; Change savings equation Given different savings opportunities, but must decide When to use one lever versus another? What impediment is most salient? What distribution channels reach the saver? What resources will the savings partner contribute? What type of saving are we trying to support? A long-term research agenda Savings/“Cost” ratio for different approaches But costs vary widely: direct costs, opportunity costs, monetary costs, others Relative efficacy Most experiments test interventions one at a time Impact on total household financial activities Incremental gross savings? Impact on net savings (saving less borrowing)? Effect on non-financial outcomes Family structure Network resources