CIFE An Examination of Current Practices in Identifying Occupant

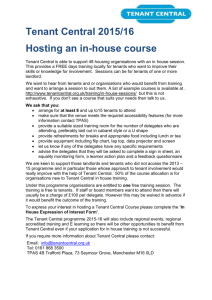

advertisement