Rhetorical Problems, Tangible Outcomes P R O

advertisement

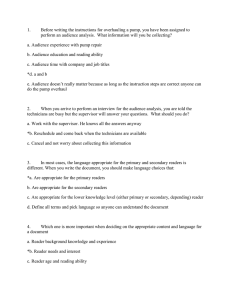

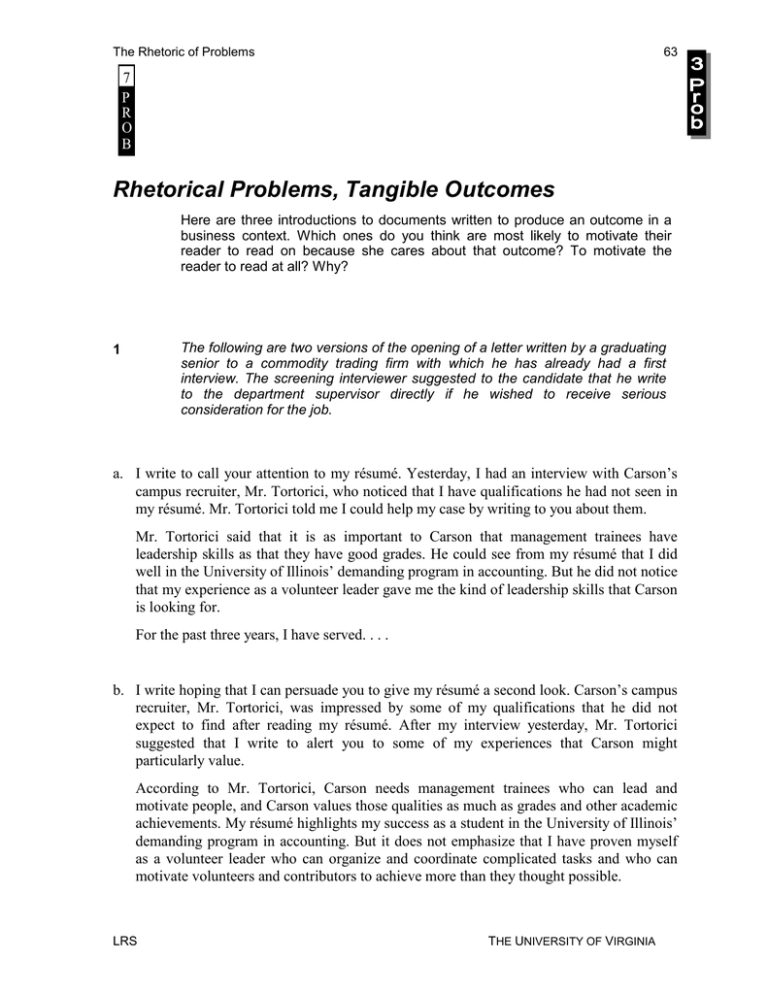

The Rhetoric of Problems 63 7 P R O B Rhetorical Problems, Tangible Outcomes Here are three introductions to documents written to produce an outcome in a business context. Which ones do you think are most likely to motivate their reader to read on because she cares about that outcome? To motivate the reader to read at all? Why? The following are two versions of the opening of a letter written by a graduating senior to a commodity trading firm with which he has already had a first interview. The screening interviewer suggested to the candidate that he write to the department supervisor directly if he wished to receive serious consideration for the job. 1 a. I write to call your attention to my résumé. Yesterday, I had an interview with Carson’s campus recruiter, Mr. Tortorici, who noticed that I have qualifications he had not seen in my résumé. Mr. Tortorici told me I could help my case by writing to you about them. Mr. Tortorici said that it is as important to Carson that management trainees have leadership skills as that they have good grades. He could see from my résumé that I did well in the University of Illinois’ demanding program in accounting. But he did not notice that my experience as a volunteer leader gave me the kind of leadership skills that Carson is looking for. For the past three years, I have served. . . . b. I write hoping that I can persuade you to give my résumé a second look. Carson’s campus recruiter, Mr. Tortorici, was impressed by some of my qualifications that he did not expect to find after reading my résumé. After my interview yesterday, Mr. Tortorici suggested that I write to alert you to some of my experiences that Carson might particularly value. According to Mr. Tortorici, Carson needs management trainees who can lead and motivate people, and Carson values those qualities as much as grades and other academic achievements. My résumé highlights my success as a student in the University of Illinois’ demanding program in accounting. But it does not emphasize that I have proven myself as a volunteer leader who can organize and coordinate complicated tasks and who can motivate volunteers and contributors to achieve more than they thought possible. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 64 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B For the past three years, I have served. . . THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 65 7 P R O B 2 The following is the opening of a memo written by a junior member of a management consulting firm, addressed to the firm’s Executive Committee. The Executive Committee has been discussing the general issue of relocating employees, but is hearing about job counseling for spouses for the first time. Among the issues yet to be decided for the proposed Employee Relocation Assistance Program is the need for job counseling for spouses. In FY 94, of the eighteen employees offered cross-country transfers, thirteen requested help with a job search for their spouses. The firm denied the requests of seven employees, four of whom decided not to accept the transfer. The Firm has no specific policy for authorizing requests for such assistance, nor does it have any standard resources for assisting spouses in a job search. Since many employees have working spouses, the Firm can anticipate increasing difficulties not only in agreements to transfer but in recruiting new employees. I have identified several relocation firms that can provide the needed services at a reasonable cost. Following is a summary of my research, an outline of proposed policy guidelines, and list of recommended job counseling firms in Charlotte, Houston, and Los Angeles. 3 The following is the opening of a memo by an apprentice stock broker at a large brokerage office, addressed to the office manager. The assignment was given by the assistant manager. The manager has heard about new furniture arrangements once before, in a meeting concerning many assorted matters. I was asked to investigate the possibility of rearranging the office modules. In the beginning, I gave a lot of thought to rearranging and reusing the modular wall system already in place. Since then I have revised my original plan several times, sometimes using the existing wall system and sometimes considering purchase of one of the newer modular systems with work stations and moveable storage options. These alternate plans were the basis on which I weighed our needs in view of our enlarged duties and added staff, both full and part time. My research has generated three viable plans and a set of priorities for deciding about a new office arrangement. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 66 7 P R O B The Rhetoric of Problems Among the issues yet to be decided for the proposed Employee Relocation Assistance Program is the need for job counseling for spouses. In FY 94, of the eighteen employees offered cross-country transfers, thirteen Predicament #1 (old requested help with a job search for their spouses. TheCost information) #2 firm denied the requests of seven employees, four of Predicament #2 (new whom decided not to accept the transfer. The Firm hasPredicament #3 (based on writer’s information) no specific policy for authorizing requests for suchanalysis of the situation) assistance, nor does it have any standard resources for assisting spouses in a job search. Since many employees Cost #3 have working spouses, the Firm can anticipate increasing difficulties not only in agreements to transfer but in recruiting new employees. I have identified several relocation firms that can provide the neededPromise of a Solution services at a reasonable cost. Following is a summary of my research, an outline of proposed policy guidelines, and list of recommended job counseling firms in Charlotte, Houston, and Los Angeles. A problem for the writer, but so far I was asked to investigate the possibility of rearranging nothing for the reader to be the office modules. In the beginning, I gave a lot of concerned about. thought to rearranging and reusing the modular wall system already in place. Since then I have revised my original plan several times, sometimes using the existingA suggestion of a problem in “our wall system and sometimes considering purchase of oneneeds,” but a very weak one at of the newer modular systems with work stations andbest. What’s the Cost? moveable storage options. These alternate plans were So what? What is the reader the basis on which I weighed our needs in view of oursupposed to concern herself with? enlarged duties and added staff, both full and part time.Why? My research has generated three viable plans and a set of priorities for deciding about a new office arrangement. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 67 7 P R O B Identifying Costs in Tangible Problems Effective documents motivate their readers by articulating a problem that the readers have and the document can help to resolve. Although some situations are so obviously problems that anyone would want to see them solved, you can only be sure that your readers understand your problem as you do if you articulate not only the Predicament or situation itself, but also the Consequences that make the Predicament a problem worth solving. And for a tangible problem, those Consequences had better feel to readers like real costs they don’t want to pay. The following is the first page of an unsolicited proposal prepared by engineering students and submitted to the City of Atlanta in preparation for the 1996 Olympics. How does it articulate costs for its readers? 4 PEOPLE MOVERS, INCORPORATED Moving Atlanta to a Brighter Future Olympic Traffic Impact Study Executive Summary The city of Atlanta faces many challenges as it prepares to host the 1996 Olympic Games. From the point of view of city services, Atlanta is in a good position to house, feed, and amuse the many Olympic visitors. Its airports and highways are adequate to bring the visitors to the city conveniently and safely. But Atlanta may not be able to move its visitors around after they arrive. Atlanta’s streets, notoriously inadequate in normal times, will be hard pressed to accommodate increased traffic during the Olympics. It can also be anticipated that the tangled layout of streets will confuse visitors, as will the city’s unusual scheme of street names. The Olympics will not succeed and Atlanta’s image will be significantly tarnished if overcrowded and confusing streets keep visitors from the events they have come to see. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 68 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B People Movers has conducted an extensive survey of Atlanta traffic patterns in order to establish a base line for predicting 1996 levels for normal volume and usage patterns as well as volume and usage patterns for the ten days of the Olympic festival. Based on those data, People Movers has formulated a staged ten-point plan for limiting peak volume and improving usage patterns during the Olympic festival. Fully implemented, this plan will assure that Atlanta’s visitors and residents can use the streets with minimal difficulty. . . . THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 69 7 P R O B You can find the Costs of a tangible problem that are most likely to motivate readers by walking up the “So what?” ladder, answering each new “So what?” as you imagine your readers would: Atlanta’s streets cannot accommodate much additional traffic. They also have a tangled layout and an unusual naming scheme. So what? I get around just fine. Why is that my problem? When Olympic visitors try to get to events at downtown venues, there will be significantly more traffic on Atlanta’s streets, which cannot accommodate much more. Also when these visitors encounter Atlanta’s tangled layout of streets and unusual scheme of street names, they will be confused. So what? When visitors try to use streets which cannot accommodate the increased traffic, they will be delayed by traffic jams. Also, if they become confused, they will get lost. So what? If the visitors are delayed or lost, they will miss the events they have come to see. So what? If visitors miss events because of traffic problems, they will blame the city. So what? With all the world watching the Olympics on TV, if visitors blame the city for making them miss events, the media will say that the Olympics have been a failure and the city’s image will be tarnished in the eyes of the world. So what? The city will lose prestige, which will cost it money because of decreased tourism and decreased business development. So what? Well . . . . LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 70 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B If your readers just keep asking “So what?”, then you have not identified Consequences that feel like costs serious enough for them to be motivated to read or act. In that case, either you have to change your approach to defining the problem or find yourself new readers who will be motivated. You know that you have identified motivating Consequences when your readers shift from “So what?” to “Oh no!” PEOPLE MOVERS, INCORPORATED Moving Atlanta to a Brighter Future Olympic Traffic Impact Study Executive Summary PROBLEM Predicament + Costs The city of Atlanta faces many challenges as it prepares to host the 1996 Olympic Games. From the point of view of city services, Atlanta is in a good position to house, feed, and amuse the many Olympic visitors. Its airports and highways are adequate to bring the visitors to the city conveniently and safely. But Atlanta may not be able to move its visitors around after they arrive. Atlanta’s streets, notoriously inadequate in normal times, will be hard pressed to accommodate increased traffic during the Olympics. It can also be anticipated that the tangled layout of streets will confuse visitors, as will the city’s unusual scheme of street names. The Olympics will not succeed and Atlanta’s image will be significantly tarnished if overcrowded and confusing streets keep visitors from the events they will come to see. People Movers has conducted an extensive survey of Atlanta traffic patterns in order to establish a base line for predicting 1996 levels for normal volume and usage patterns as well as volume and THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 71 7 P R O B usage patterns for the ten days of the Olympic festival. Based on those data, People Movers has formulated a staged ten-point plan for limiting peak volume and improving usage patterns during the Olympic festival. Fully implemented, this plan will assure that Atlanta’s visitors and residents can use the streets with minimal difficulty. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 72 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B Rhetorical Problems, Conceptual Outcomes 5 Here are three versions of an introduction to a student paper in a history class The assignment: “Compare and contrast how Thucydides in the History of the Peloponnesian Wars presents the rhetorical appeals of Corcyra and Corinth in order to give readers an insight into Athenian values.” Which version do you think is most likely to motivate its reader to read on because she cares what the paper says? Least likely? Which do you predict would get the best and worst response from the teacher? Why? a. In 433 BC, the cities of Corcyra and Corinth became involved in a dispute over which of them should rule Epidamnus. Because they could not settle the dispute between themselves, they sent representatives to Athens to appeal for its help against the other. After hearing the two speeches and debating among themselves, the Athenians finally decided to support Corcyra. As presented in The History of the Peloponnesian Wars, the two speeches differ in many ways, but the most important difference is in the reasons that each side gives to support its appeal for help. The appeals that Athens accepted and rejected can tell us something about Athenian values. In order to show these values, I will first discuss the Corcyrean speech and then the Corinthian speech. b. Just before the Peloponnesian War, Corcyra and Corinth disputed who should rule Epidamnus. Because they could not settle the dispute themselves, they appealed to Athens for help against the other. As presented in The History of the Peloponnesian Wars, the appeals that each side gave differ. The Corinthians appealed to Athens’ sense of justice and tradition, while the Corcyreans appealed to their self-interest. After debating the question, the Athenians finally sided with Corcyra’s appeal, because at this time the Athenians knew that war was coming and that they would probably need Corcyra’s naval power. When we understand the kind of appeals that the two sides made and which ones Athenians accepted and rejected, we can better recognize Athens’ real values and motives. c. When Corcyra and Corinth disagreed over control of Epidamnus in 433 BC, they each went to Athens to ask for help against the other one. As presented in The History of the Pelloponesian Wars, the Corinthian speech appealed to Athens’ sense of honor and justice, while the Corcyrean one appealed to their self-interest. Since it was in Athens that Socrates and Aristotle first taught about honor and justice, it would be easy to assume that Athens would side with Corinth and its appeal to higher values. But they sided with Corcyra, revealing that in this instance Athenians were motivated by selfinterest. Unless we recognize that right from the earliest episodes in the war Athens rejected justice when it contradicted their self-interest, we will misjudge their real motives when they later defended some of their cruel actions by calling them just. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 73 7 P R O B Athens showed its real values when it rejected justice and honor in favor of future selfinterest. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 74 7 P R O B The Rhetoric of Problems In 433 BC, the cities of Corcyra and Corinth became involved in a dispute over which of them should rule Epidamnus. Because they could not settle the dispute between themselves, they sent representatives to Athens to appeal for its help against the other. After hearing the two speeches and debating among themselves, the Athenians finally decided to support Corcyra. As presented in The History of the Peloponnesian Wars, the two speeches differ in many ways, but the most important difference is in the reasons that each side gives to support its appeal for help. The appeals that Athens accepted and rejected can tell us something about Athenian values. In order to show these values, I will first discuss the Corcyrean speech and then the Corinthian speech. When Corcyra and Corinth disagreed over control of Epidamnus in 433 BC, they each went to Athens to ask for help against the other one. As presented in The History of the Pelloponesian Wars, the Corinthian speech appealed to Athens’ sense of honor and justice, while the Corcyrean one appealed to their self-interest. Since it was in Athens that Socrates and Aristotle first taught about honor and justice, it would be easy to assume that Athens would side with Corinth and its appeal to higher values. But they sided with Corcyra, revealing that in this instance Athenians were motivated by selfinterest. Unless we recognize that right from the earliest episodes in the war Athens rejected justice when it contradicted their self-interest, we will misjudge their real motives when they later defended some of their cruel actions by calling them just. Athens showed its real values when it rejected justice and honor in favor of future self-interest. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS A Predicament for Athens, but not for the reader. All old information so far. So the speeches differ; what two speeches don’t? So what if they give different reasons? A hint of a problem, if the reader already cares about Athen’s values. No question or answer; only a topic. All old information so far. Common, but mistaken assumption. Problem; raises implied question: “How can A act on such base motives?” Cost in the form of poor understanding; raises implied question: “What are A’s real motives?” Gist of an answer. The Rhetoric of Problems 75 7 P R O B Identifying Costs in Conceptual Problems For Conceptual Problems, you motivate readers to care enough to read on by identifying Consequences that make them want to know more. But since Conceptual Problems center around Questions rather than Predicaments, their Consequences will involve those things that come with not knowing answers: ignorance and misunderstanding. Sometimes, you can also find distant tangible consequences that are associated with that ignorance or misunderstanding. The following is the introduction to an honors thesis. In this case, the writer raises two related questions, one about O’Connor and one about one of O’Connor’s critics. How does she show readers how those questions have consequences they should care about? 6 Two Tickets to Sacrifice: Racism and Activism in O’Connor’s Short Stories In 1959 Flannery O’Connor was invited to meet with James Baldwin but declined the offer. She explained in a letter that his visit to Georgia “would cause the greatest trouble, disturbance and disunion”. After reading this, a reader could conclude that O’Connor was racist. But did she refuse to see Baldwin because he was black? In a 1964 letter, she hinted at the real reason: About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind. Very ignorant but never silent. Baldwin can tell us what it feels like to be a Negro in Harlem but he tries to tell us everything else too. King I don’t think is the age’s great saint but at least he’s doing what he can do & has to do . . . (Letters, 580) O’Connor disliked Baldwin not because he was black, but because of his overbearing approach to race. Although she supported the idea of racial equality, she denounced Baldwin’s means of achieving it. But the ambiguous treatment of race here and throughout her work remains a difficult subject for her admirers, who are unwilling to cast her aside as another Southern racist. In her Introduction to The Habit of Being, Sally Fitzgerald tries to excuse O’Connor’s puzzling presentation of race and save her place in the canon by explaining it as the product of “an imperfectly developed sensibility” (Letters, xvi). She notes that “large social issues as such were never the subject of her writing,” and adds that O’Connor “was never in danger on the score of racism” (xix). Fitzgerald’s analysis, however, is only half true. Large social issues were not the subject of O’Connor’s writing, but her attitudes concerning race cannot be dismissed as the product of LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 76 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B an imperfectly developed sensibility. They were well-developed and firmly based intellectually in her religious beliefs. For her, racism was not a social issue but the symptom of a larger spiritual and religious crisis. To O’Connor, to treat racism as a social problem is to misunderstand it. Analysis of her best known short stories shows that her treatment of racism as a spiritual crisis was more sympathetic to racial equality than is apparent and, far from indicating that racism was an aberration in her life, they suggest that O’Connor had an understanding of racism that set her apart from liberals of her time. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 77 7 P R O B For conceptual problems, you can find the Consequences most likely to motivate readers by walking up the “So what?” ladder, answering each new “So what?” as you imagine your readers would. But in this case, the answers will involve not painful costs but unsatisfying ignorance or misunderstanding. Flannery O’Connor’s treatment of race is ambiguous. Implied question: “Are there elements of racism in O’Connor’s work?” a So what? Why is that my problem? If we cannot decide whether there are elements of racism in O’Connor’s work, then we will not be able to decide how to understand and value that work. So what? If we cannot decide how to understand and value O’Connor’s work, then we will not know whether we should read her with appreciation. So what? If we do not know whether to read O’Connor’s work with appreciation, then we will not know how we should place her in the canon of American authors. So what? Well . . . Sally Fitzgerald’s exculpatory explanation of O’Connor’s treatment of race is only half true. Implied question: “Is there an acceptable explanation that O’Connor’s treatment of race is not entirely racist?” b So what? Why is that my problem? If we cannot accept this explanation, then we will not be able to decide how to understand and value O’Connor’s work. So what? If we cannot decide how to understand and value O’Connor’s work, then we will not know whether we should read her with appreciation. Etc. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 78 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B You know that you have identified motivating Consequences of a conceptual problem when your readers shift from “So what?” to “Tell me more.” Two Tickets to Sacrifice: Racism and Activism in O’Connor’s Short Stories In 1959 Flannery O’Connor was invited to meet with James Baldwin but declined the offer. She explained in a letter that his visit to Georgia “would cause the greatest trouble, disturbance and disunion”. After reading this, a reader could conclude that O’Connor was racist. But did she refuse to see Baldwin because he was black? In a 1964 letter, she hinted at the real reason: About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind. Very ignorant but never silent. Baldwin can tell us what it feels like to be a Negro in Harlem but he tries to tell us everything else too. King I don’t think is the age’s great saint but at least he’s doing what he can do & has to do . . . (Letters, 580) PROBLEM Question + Costs PROBLEM Question + Implied Costs O’Connor disliked Baldwin not because he was black, but because of his overbearing approach to race. Although she supported the idea of racial equality, she denounced Baldwin’s means of achieving it. But the ambiguous treatment of race here and throughout her work remains a difficult subject for her admirers, who are unwilling to cast her aside as another Southern racist. In her Introduction to The Habit of Being, Sally Fitzgerald tries to excuse O’Connor’s puzzling presentation of race and save her place in the canon by explaining it as the product of “an imperfectly developed sensibility” (Letters, xvi). She notes that “large social issues as such were never the subject of her writing,” and adds that O’Connor “was never in danger on the score of racism (xix).” Fitzgerald’s analysis, however, is only half true. Large social issues were not the subject of O’Connor’s writing, but her attitudes concerning race cannot be dismissed as the product of an imperfectly developed sensibility. They were welldeveloped and firmly based intellectually in her religious beliefs. For her, racism was not a social issue but the symptom of a larger spiritual and religious crisis. To O’Connor, to treat racism as a social problem is to misunderstand it. Analysis of her best known short stories shows that her treatment of racism as a spiritual crisis was more sympathetic to racial equality than is apparent and, far from indicating that racism was an aberration in her life, they suggest that O’Connor had an understanding of racism that set her apart from liberals of her time. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 79 7 P R O B 7 The following text is a cover letter for a formal proposal to receive funding for an HIV-AIDS education program. The letter was written by the Director of Development and External Relations at a university in Florida. The reader of the letter is the Executive Director of a foundation that makes grants to health education programs and organizations. Eastern Florida University Office of Development and External Relations 22 Administration Bui lding 300 North College Avenue Sei tonvill , Florida 27652 (204) 684-2739 March 19, 1995 Mr. Michael Garvarich Executive Director The Bryant Foundation 423 Third Street, Suite 300 Gainesville, Florida 94013 Dear Mr. Garvarich: Florida ranks first in the country with the highest transmission rate for HIV among heterosexuals, second in the number of pediatric cases and third in the number of total AIDS cases. Until a cure for HIV-AIDS is found, the most effective way of preventing the spread of the virus is through education of our youth. Recognizing the Bryant Foundation’s commitment to the HIV-AIDS battle, we request that you consider a gift of $79,200 to fund two years of two peer education programs entitled INFO-AWARE and AWARE THEATER at the HIV-AIDS Institute at Eastern Florida University in Seitonville, Florida. Designed to reach thousands of middle school, high school, and college students throughout eastern Florida, the programs should have an enormous impact on the Florida battle for HIV-AIDS prevention. The goal of the HIV-AIDS Institute at Eastern Florida University is to take the two AWARE programs, INFO-AWARE and AWARE THEATER, into 300 schools and colleges in the next academic year, reaching an estimated 75,000 young people aged 12-23. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 80 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B The INFO-AWARE program involves training student volunteers by providing accurate information for them to relate to their peers. The initial target volunteers are white, black, and Latino middle and high school students recommended by their teachers. Once educated, these students will go into classrooms and share their knowledge with others like themselves. Because young people learn in various ways and because visual presentations are often understood better and retained longer than written THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 81 7 P R O B Mr. Michael Garvarich 2 March 19, 1995 documents, Institute Director Sharon Patton has also developed the AWARE THEATER, a second program that is designed to target young people by using live performance and video. Cooke County Community College has already joined in the Institute’s efforts and volunteered a group of theater students ready and willing to be trained and to go on the road by this June. To our knowledge, no other HIVAIDS education group has taken the approach of the AWARE THEATER. Our design and concept could easily be imitated across the country. To fully implement both the INFO-AWARE and AWARE THEATER programs, the HIV-AIDS Institute at Eastern Florida University needs a cadre of young volunteers, the approval of the east Florida community, and initial funding of $79,200 (please see attached budget). Approval has been granted by the Cooke County and Turner County Public Schools, and community college students are in line to form the AWARE THEATER troupe. The Institute has already received some funding from the State of Florida and from the Center for Disease Control to serve as money for INFO-AWARE program materials and start-up funds. W e now seek additional sources of revenue to enhance the INFOAWARE program and to implement the AWARE THEATER program. Support from the Bryant Foundation would enable us to pay peer educators (an additional benefit to young people needing jobs) and a full-time coordinator for the INFO-AWARE program; it would also fund a training conference, props and scenery, transportation, and publicity for the AWARE THEATER. A gift of $79,200 would assure the full implementation of both AWARE programs by the fall of 1993. Thank you for your thoughtful consideration of our proposal. The Eastern Florida University HIV-AIDS Institute is a worthwhile recipient of a Bryant Foundation grant and a good investment for the Foundation. Your published interests in youth, health, education, and the HIV-AIDS epidemic are all addressed by both of the Institute’s AWARE programs. I will call you the week of April 5 to verify the LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 82 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B arrival of our materials and to answer questions about our proposal or budget; in addition, please feel free to call me any weekday at (407) 765-2279 if there is any additional information you would like. Sincerely, Lisa Phillips Director of Development and External Relations Enclosures: Proposal, Project Budget, IRS Determination Letters (2), Audited Financial Statement THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 83 7 P R O B 8 GARY & LIST CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS J. Williams Gary, C.P.A. K. Garner List, C.P.A. Janine R. Starr, C.P.A. Robert L. Windower, C.P.A. Kim Sung-Flowers, C.P.A. 1300 E. Columbus Street P.O. Box 1928 Corvallis, Oregon 73584 Phone 802/601-3902 FAX 802/601-2548 INSPECTION PROGRAM REPORT, YEAR ENDING DECEMBER 31, 1996 The firm’s inspection program has been completed for the year ending December 31, 1996. The inspection program includes a sample review of some of our clients’ files. Reviews of workpapers, audit program, checklists, and so forth are performed in order to see that all staff follow procedures and apply them consistently. The purpose of the inspection is to help us all improve the quality of our work in this office and to prepare for our next peer review in May of 1997. The following is a list of eleven findings from the inspection: 1. INDEPENDENCE Our review disclosed a case where our firm was not independent of a client and where this fact was not noted in our report. A compilation report was issued but the statement that the firm was not independent was not included. Everyone in the firm signs a statement on independence annually, but not everyone may have available the list of clients of which we are not independent. The following is a list of clients of which we are not independent as of November 30, 1996: [list of clients] 2. CHECKLIST FOR COMPILATION AND REVIEWS Last year we issued a policy memo with information about signing off on audit steps in the audit programs. However, it LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 84 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B appears that we may have been somewhat lax about signing off on the compilation and review checklists. We need to be sure that these checklists of procedures are followed to the letter and then signed off. If you have a question about a procedure, ask one of the partners for an explanation. As a reminder, disclosure checklists also need to be completed for each financial statement prepared when notes are included. In addition, a cover sheet is required on the compiled and reviewed financial statement. The cover sheet must list “date prepared,” “reviewed by,” “typed by” and “footed by,” and “signed by.” As each step is completed, it must be dated and signed. Our review noted that the “reviewed by” and “signed by” steps were not always completed as required. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 85 7 P R O B The following introductions are from three honors theses, two in history and one in English. Which of the three articulate a problem based on a question that a reader might be willing to care about long enough to read on? 9 a. Parnell and deValera Crises: Two Challenges to the Irish Consensus During their time, Charles Stewart Parnell and Eamon de Valera were at one point the most powerful men in Ireland. By leading the Irish consensus, which involved the relationship between the Leader, the Party, and the Bishops, Parnell and deValera were able to develop constitutional states in Ireland. In 1890, Parnell attempted to undermine the consensus he created when his role as Leader was threatened. In 1921, de Valera tried to disrupt the consensus he led when it was evident that the Irish Republic was jeopardized by the Treaty with Great Britain. The Party and the Bishops were not only able to bring down their leaders in both cases, but also the Irish consensus was able to reconstruct itself after each constitutional crisis. To understand the Parnell and de Valera crises, we must understand the consensus Parnell constructed between 1880 and 1890. Then Parnell’s challenge to the constitutional system and the Irish Parliamentary Party he built must be examined, as well as the survival of the Irish Party up to 1918. The rise of Sinn Fein under de Valera during and after 1918 and the Anglo-Irish war up to the Treaty will also be investigated. After the Treaty, de Valera’s challenge to the Irish consensus and the resulting Irish civil war will be scrutinized. Finally, the survival of the Irish consensus and the evolution of a more democratic Irish political system will be developed. b. The Neutral and Natural Effects of Love and War in Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms Ernest Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms is a novel which carefully and concisely blends the themes of love and war, and other themes based on this grand scale of love and death. The main themes of love and war and the bliss and tragedy in both originate, develop, and intermix, often coinciding and coexisting in certain sections of the novel, depicting life as it is. The result of this intermixing necessitates a fusion of the idyllic or comic, and the tragic or disturbing which is certainly affected by the impending doom of the war. A Farewell to Arms is a story about the love of two people affected by the disastrous events that happen during this period of war. It is a narrative which, with meticulous care, follows the development of the psychological characteristics of the two lovers, Catherine Barkley and Frederic Henry, as they encounter tragic and idyllic settings, thus developing their relationship amidst the unstable, insecure surroundings of a country at war. Hemingway writes the story of the two lovers as they represent average LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 86 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B human beings in their emotions, thoughts, and actions in a natural and neutral world of love and war. In A Farewell to Arms Hemingway describes the story of the lovers as they stand on unstable ground during this uneasy period, coupled with and comforted by the neutral territory they always seem to find amidst the natural instability of their surroundings as a whole. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 87 7 P R O B c. Francisco Bulnes: Counter-Revolutionary Polemicist My attitude is not one of enmity toward the Mexican Revolution. . . But when the people who revolt lack the necessary reactionary power to reconstruct their country, they perish as a nation . . . I am not an enemy of the revolution, but I do look with horror upon its progress, because Mexico is my native land and from the final, supreme test of the revolution may result in the loss of its independence .... With this statement, Francisco Bulnes prefaces The Whole Truth About Mexico, a critique of the Mexican Revolution which testifies to the culpability of the United States in seeking to implant in Mexico an Anglo-Saxon notion of liberty that lacks logical basis or understanding of the Mexican people. According to Bulnes, such a program orchestrates the demise of Huerta and nurtures the “de facto anarchy” and despotism of Caranza. To change US policy, Bulnes went on to construct a caustic but confusing polemic that some critics think is merely one more Mexican nationalist. Others have claimed that while Bulnes’ critical re-thinking of the Porfiriato was visionary, it represented only a crisis of Nineteenth Century Positivism. But those views underestimate his role as a seminal transitional thinker and as the deeply philosophical and influential polemicist that he was. We believe that his writings were an attempt to adjust to an intellectual perspective more attuned to Twentieth Century modernity. He provides an unexpected link between the late Nineteenth Century Cientifico program and the post-Revolutionary, Twentieth Century organization of Mexican political and social life. While we may marvel at Bulnes’ visionary ability to predict programs implemented by the “institutionalizing” forces of Revolutionary Mexico, it would be a mistake to overlook his contribution to the modern Mexican state, because there is evidence that Bulnes was widely read and debated in the later literature of the 30’s, and 40’s, evidence suggesting that he may have influenced later policy-makers, as well. This paper will clarify three areas of Bulnes's interpretation of the Mexican Revolution: the agrarian question, the collapse of the Porfiriato, and U.S./Mexican relations, in order to explain how Bulnes elucidated a connection between the Porfiriato and the formation of the modern Mexican State and hinted at ways in which various sectors could maximize social and political restructurings to advance Mexican development. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 88 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B Rhetorical Problems: Three Essential Elements We commonly describe problems in one of three ways: in a word (e.g., cancer, homelessness); in a phrase (e.g., poor study habits, slumping profits); or in a question (e.g., How do we improve our employee training program?). These descriptions are fine for most purposes. But for the purpose of formulating a rhetorical problem that organizes a document, you have to identify three components: (1) A Destabilizing Condition; (2) Some Consequences of that Condition; and (3) Readers Who Care. 1. A Destabilizing Condition, either a Question or a Predicament A Destabilizing Condition is some particular situation that has the potential to cause difficulty, either physical or conceptual. An example: SAT scores have declined and show no signs of rising. A situation is a Destabilizing Condition only in relation to a specific Consequences for specific readers. Some Conditions are so fraught with difficulty that they seem inherently destabilizing. For example, a plague that kills thousands would seem to be a problem no matter the circumstances. But if you were a citizen of Troy, and the plague ran through the Greek troops that were besieging your city, then that plague would pose no problem. It would, in fact, be the solution to a problem. The point is this: Destabilizing Conditions are situations that threaten trouble. They are identifiable only in relation to the trouble – the Consequences – they bring. If they do not bring trouble, then they are no problem. Destabilizing Conditions come in two forms: Predicaments that create Pragmatic Problems and Questions that create Conceptual Problems. 2. Consequences of the Condition In order to matter, the Consequences of a Condition must (a) affect your readers, directly or indirectly, and (b) be recognized and accepted by your readers (or your readers are at least willing to consider them). Consequences take two forms, either the Costs of leaving the Condition unresolved or the Benefits of resolving it. (Costs and Benefits are often mirror images of one another.) Here’s our SAT example again: THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 89 7 P R O B SAT scores have declined and show no signs of rising. CONDITION If SAT scores reflect achievement, then our workforce is becoming less well educated, which will put the U.S. at a disadvantage in an international marketplace, weaken the economy, and reduce the standard of living for many of us.COST LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 90 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B 3. Readers Who Care about the Cost When you construct rhetorical problems you can only count something as a Consequence if your readers recognize it and accept it as a Cost or lost Benefit. For professional writers, there is no such thing as a problem that every reader will consider to be inherently worth acting upon. Remember that earlier we said a Destabilizing Condition is only destabilizing in relation to its Consequences; likewise, a Cost or Benefit is only a Consequence in relation to the specific group of readers it matters to – a specific community of interest that will care enough about the Consequence to act on the problem. When you formulate a problem, you have to be certain that what you present as a Consequence is indeed undesirable to your particular readers – and serious enough for them to bother about it. Let’s take a look at our SAT example again: SAT scores have declined and show no signs of rising. CONDITION If this author were writing an editorial and wanted to appeal to parents who expect their children to go to good colleges, he might attach the following Cost to the Condition: SAT scores have declined and show no signs of rising. CONDITION If children get low SAT scores, they may not get into a good college, and their prospects for a comfortable and satisfying life will be reduced. COST On the other hand, if he wanted to appeal to employers who must compete in a global marketplace with undereducated workers, he might attach this Cost: SAT scores have declined and show no signs of rising. CONDITION If SAT scores reflect achievement, then our workforce is becoming less well-educated, which will put the U.S. at a disadvantage in an international marketplace, thereby weakening the economy and reducing the standard of living for many of us.COST And notice that this Cost would also work if our writer wanted to appeal to varied readers with differing interests – for example, everyone who stands to have their standard of living reduced; employers who have to be competitive in a global marketplace; educators who want more funding for schools. The point is this: the Consequences you choose to state in your document must be appropriate to your particular readers. In business and professional situations, you must carefully tailor your Costs or Benefits to the specific needs of your readers in order to convince them to act. In academic situations, you must tailor the Consequences of not knowing something to the THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 91 7 P R O B specific interests of your readers in order to convince them to change their minds. LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 92 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B Sometimes business and professional writers write because someone has come to them with a problem. In this case, you have only to keep your eye focused on your reader’s problem and address the Consequences your reader has already explained to you. Just as often, however, business and professional writers write because they have discovered a problem that their readers do not yet recognize, or because they have a problem that their readers can help them resolve if they can be convinced to act. In this case, your job is to formulate the problem in such a way that your readers are persuaded to act because they recognize the Costs or lost Benefits that the problem means to them. If you are the boss, then your task is made a little bit easier: your problems are necessarily your subordinates’ problems, although it pays to be persuasive rather than tyrannical. But if you’re not the boss, you must find some way to get your readers to care about the Consequences you see in your problem – or, more frequently, you must find some other Consequences that your readers do, in fact, care about. And you may face one additional challenge as a professional writer: almost every document you write will be read by multiple readers with differing interests. Therefore you must formulate your problem in terms of Consequences that all of these groups of readers will accept. Readers will try to understand your document in terms of the problem or question it purports to resolve. Your job is to inform or, if necessary, to persuade readers why the problem is important to them. You do not persuade readers that your problem is their problem just by presenting the condition that brings the problem about, nor by emphasizing the problem’s interest or importance, nor by stressing the many difficulties associated with it. To sell readers on your THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 93 7 P R O B problem you must emphasize the particular Consequences — Costs or lost Benefits — for your particular readers. LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 94 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B Destabilizing Conditions in Conceptual Problems: Questions In conceptual problems, Destabilizing Conditions are always some form of question, something your readers do not know or do not understand, but should. What is destabilized in a Conceptual Problem is your readers’ minds. When looking for the destabilizing element in a Conceptual Problem, look for words like these: an overlooked connection or disjunction unexplained differences or similarities what seems to be the case is not inability to find a pattern unaccounted for data excessive complexity a gap in knowledge unpredictability inconsistency aberrant facts contradiction disagreement discrepancy uncertainty perplexity confusion ambiguity unclarity anomaly THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 95 7 P R O B surprise conflict paradox error LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 96 The Rhetoric of Problems 7 P R O B Consequences in Conceptual Problems: More Questions The Consequences of a conceptual problem can be hard to state because they are normally abstract consequences that you cannot readily point to. Typically, the Cost of a conceptual problem is that if the Destabilizing Condition is not resolved, your readers will also fail to understand or appreciate something else that is still more important than the Destabilizing Condition alone. Similarly, the Benefits of resolving a conceptual Destabilizing Condition is that your readers will understand more than they now do. A conceptual problem must have Consequences that go beyond the puzzle or question inherent in the Destabilizing Condition. Because conceptual Costs or Benefits can be hard to state, it is particular dangerous for writers to assume that their readers already understand them. However, when you articulate the Consequences explicitly, • you make sure that you understand both the Consequences and their relation to the Condition; • you may discover more Costs and Benefits than you thought you knew; • you may discover additional Destabilizing Conditions related to the one with which you began; • you may discover intermediate Conditions and/or Consequences that link your original Condition with the assumed Consequences; • you guard against overestimating what your readers know and, especially, what they will accept. Readers of Conceptual Problems In order to see a conceptual problem as a problem, readers have to share the body of knowledge and ways of thinking that are disrupted by the Destabilizing Condition. Few of us would find our conceptual landscape destabilizing if we found out that the Dead Sea Scrolls were a fraud. But for those working in the history of Judeo-Christian religions, such a revelation would be shattering. Its Cost would include not only having to change their minds about many things they now believe, but also rewriting textbooks, abandoning research programs, perhaps even ruining a few careers. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 97 7 P R O B Since conceptual problems destabilize knowledge, ideas, understanding, they are only problems for readers who understand things in a certain way. Conceptual problems tend to be tied to groups of readers who share knowledge, hold many of the same beliefs, and mostly understand things in the same or related ways. In both academic and professional life, such groups are organized around disciplines. What counts as a problem worth writing about for one discipline, might or might not count for those outside. LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 98 The Rhetoric of Problems Revising on the Page 7 P R O B Finding a Problem Worth Writing About Tangible Problems Usually, we write about a tangible problem not because we sought it out but because it has jumped up to bite us. Few people go around looking for tangible problems to write about. Instead, they write about a tangible problem because they face a problem that they believe can be solved by writing to enlist others in solving it. That is way documents that deal with tangible problems almost always focus on action — whatever action the writer wants her readers to take or support in order to resolve the problem. So when you ask whether a tangible problem is worth writing about, apply these tests: 1. Do you need readers to help you address the problem? Are you readers in a position to provide you the help you need? 2. Are the Costs of the Predicament to the reader greater than the Cost to the reader of taking action to resolve it? 3. Are the Costs of the Predicament to you greater than the Cost to you of the writing and everything else you have to do to resolve it? If your teacher gives you an assignment to find a tangible problem to write about, your best bet is to find someone who has a problem that meets those three tests. Conceptual Problems Most classroom writing involves conceptual problems, often conceptual problems that the student must invent in order to write about it. Here are some steps for creating and evaluating a conceptual problem at three different stages in the writing process. I. While you are reading and researchi ng 1. Name your topic: Describe your topic with at least one nominalization that could be a specific verb. That is, do not describe your topic like this: I am working on stories about the Battle of the Alamo . . . THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 99 Revising on the Page 7 P R O B Instead, include at least one substantive nominalization: I am working on the evolution of stories about the Alamo . . . 2. Describe what you (or your readers) do not know about it: To your first clause, add another one that contains an indirect question of the form: because I want to find out who/what/when/where/why/how/whether . . . I am working on the evolution of stories about the Battle of the Alamo because I want to find out how the stories became part of our national mythology . . . LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 100 The Rhetoric of Problems Revising on the Page 7 P R O B 3. Add a rationale for finding out what you don’t know: Complete your sentence with a clause that states a purpose for answering your question: . . . in order to understand better how/why/ whether . . . I am working on the evolution of stories about the Battle of the Alamo because I want to find out how the stories became part of our national mythology in order to understand better why stories about military defeats come to represent nationalistic values. 4. Change the perspective from yourself to your readers: Remember, readers are less motivated to find out what you don’t know and why you should than to find out what they don’t know and why they should: I am working on the evolution of stories about the Battle of the Alamo because I want to show you how the stories became part of our national mythology in order to explain to you why stories about military defeats come to represent nationalistic values. NOTE: You are unlikely to be able to complete steps 3 and 4 until you have made some progress in learning about your topic. II. After you have a draft If you are like most academic writers, you get some of your best ideas as you write and revise. If so, once you have completed a revisable draft you should suspect that at least two things are true: (1) Your paper has more real potential after you draft it than it did before, if only you can find where that potential is; and (2) whatever you said about your problem in your first draft of an introduction does not quite match what you did in your paper. So follow these steps as soon as you have a revisable draft. In order to show you the steps, we’ll use the following fairly typical paper Western Civ paper as an example (this excerpt includes the first two and the last three paragraphs): The Church and its Crusades During the eleventh through thirteenth centuries, the Roman Catholic Church initiated several Crusades against the Muslims in the Holy Lands. The Pope would usually instigate and call for armament and support for this endeavor. Pope Urban II started the first Crusade in 1096. His predecessor, Gregory VII, had also petitioned to get support for a crusade in 1074 but did not succeed in launching his Crusade. There are written statements from these Popes concerning the Crusades. Pope Urban II in “Speech at the Council of Clermont” in the THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 101 Revising on the Page 7 P R O B year 1095 calls for a Crusade and Pope Gregory VII in a Letter to King Henry IV during the year 1074 also proposes a Crusade. Both the text preceding Urban’s speech and Urban’s speech mention several serious problems within the society, both lay and clerical. At the end of his speech, Urban discusses the need for a Crusade. The introductory text, The Version of Fulcher of Chartes, including His Description of Conditions in Western Europe at the Time, furnishes some background information about controversies which Urban does not discuss in his speech and he also summarizes and emphasizes the important points in the Pope’s speech. . . . . . . . (cont’d) LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 102 The Rhetoric of Problems Revising on the Page 7 P R O B . . . The concept of using the Crusades not as a purely religious project but as a means of political unity can also be seen in Gregory’s letter. One reason he wishes to go on a Crusade is the chance that the Roman and Orthodox Churches might reconcile. They have held different views on the place of the Holy Ghost in the Trinity, and the Eastern Church also did not recognize the Pope’s authority. Hopefully, with a successful Crusade, both of these schisms could be rectified. They were to hold a conference to discuss the Holy Ghost and also the Eastern Church would accept the authority of the Roman Pope. Then all of Christianity would be under the guidance of one Church and not two separate Churches. Another subtle coalescence is between the Church and the Empire. The beginnings of the power struggle between the Pope and Emperor occur during the reigns of Henry IV and Gregory VII. The Pope is head of the Church and the Emperor is head of the Empire. When Gregory assures Henry of his affections and says that he will leave the Church under the care of Henry if he, Gregory, goes on the Crusade, this could show that Gregory wishes to prove that the Church and the Empire are still united and should work towards a common goal. Perhaps Gregory wishes to prevent a power struggle between the Pope and Emperor, so his proposal for a Crusade may also be a suggestion that the Church and the Empire unite to fight a common enemy instead of fighting amongst themselves. The Popes, Urban II and Gregory VII, heralded the Crusades as a way to restore the Holy Lands to Christian rule, but in fact, they also used the concept of the Crusades as a means to achieve a form of unity important to them during their pontificate. During Urban’s pontificate, he could establish his authority, fight the devil (Muslims), and control fighting amongst the Europeans and direct those energies elsewhere. Gregory VII wishes to achieve unification between the Roman Church and the Greek Orthodox Church. And he also seems to be trying to keep the unity or prevent the breakup of the Church and The Empire. In both cases each Pope tried to unite people in a common cause to fight against the infidels instead of amongst themselves. Therefore the Crusade was not just a fight against the Muslims to recapture the Holy Land and to save God’s faith, but it was an effort to save the Church and Europe from the dissent that was tearing it apart. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 103 Revising on the Page 7 P R O B Four Steps for Revision 1. Name your topic: Describe your paper with at least one nominalization that could be a specific verb. As I worked on the motivation of the Popes to initiate the Crusades. . . 2. Describe the most important thing that you now know about your topic: To your first clause, add another one that states what you found out: . . . the most important thing that I found out was that. . . In order to finish that clause, find the point of your paper, its main idea or main claim. You might find it in the introduction, but you are more likely to find it at the end. As I worked on the motivation of the Popes to initiate Crusades, the most important thing that I found out was that the Crusades were not just a fight against the Muslims to recapture the Holy Land, but an effort to save the Church and Europe from the dissensions which were tearing it apart. 3. Add a statement of why it is important to know what you have found out: Add another sentence that includes an implied question that is larger and more important than the one your paper has answered: Now that I know that, I can understand better the larger question of how/why/. . . To finish that sentence, you have to do some hard thinking about the significance of what your paper says. Don’t fall into the trap of just repeating your first question: Now that I know that, I understand better why the Popes ordered the Crusades. Instead, ask yourself whether there is some larger question to which your paper can be a small part of the answer. It is often helpful to make some of the terms in your first question more general: As I worked on the motivation of the Popes to initiate Crusades, the most important thing that I found out was that the Crusades were not just a fight against the Muslims to recapture the Holy Land, but an effort to save the Church and Europe from the dissensions which were tearing it apart. Now that I know that, I understand better the larger question of how the Vatican used theological rhetoric to solve pragmatic political problems in early European history. 4. Preface your statement of the problem with a description of some common knowledge or received wisdom that your paper will challenge: Add a last element: Before I/my readers knew what I found out, we thought . . . Finish that sentence with whatever ideas or information a reader will have to change as a result of reading your paper. (You can invent readers for this purpose, but it is better if there are real people who hold the views you contradict.) LRS VIRGINIA THE UNIVERSITY OF 104 The Rhetoric of Problems Revising on the Page 7 P R O B Before I/my readers knew what I found out, we believed the common myth, encouraged by the Church over the centuries, that the Crusades were motivated entirely by popular religious zeal to liberate Jerusalem and restore it to Christianity. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 105 Frequently Asked Questions 7 P R O B ? “I’m not sure what you mean by a problem. In most of my courses I write papers that answer questions, not solve problems.” The problems we’re talking about are the kinds of problems that organize documents — think of them as rhetorical problems. Rhetorical problems include some kinds of questions — the kinds of questions that your readers feel that they need to have answered. They also include what you might think of as ordinary problems. So, as we use the term, rhetorical problems are of two kinds: 1. Predicaments— Tangible, Pragmatic Problems (cancer, slumping profits, a high divorce rate, etc.) This is the most common sense of the word problem. Ordinary problems are people, things, or situations that have consequences we do not like. Ordinary problems almost always have a physical component. In order to solve them we have to act to change a person, an object, or a situation. The damage done by tangible problems is usually evident in the world around us — palpable in the form of pain, visible in the form of suffering people. Sometimes, however, tangible problems seem to be personal and “inside” us — depression, anxiety, unhappiness. But even these problems have a substantial physical component. Some academic documents, many professional documents, and most business documents deal with tangible problems. Their outcome and their point tend to involve physical actions. 2. Questions or Puzzles – Conceptual Problems (What came before the Big Bang? Why did the Anasazi Indians disappear? How do we best categorize ancient Greek vases? etc.) Conceptual problems are questions, missing facts, things misunderstood — any gap in our knowledge or understanding that bothers us, either because we need that knowledge in order to resolve a tangible problem or because we just need to know. They tend not to have a physical component. Conceptual problems are often sought out rather than avoided. For teachers and students, they are almost always good, because they are the chief currency of academic endeavor. Most academic documents, many professional documents, and some business documents deal with conceptual problems. Their outcome and their point tend to involve mental actions. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 106 The Rhetoric of Problems Frequently Asked Questions 7 P R O B ? “What about the problems on exams?” Some exam questions, especially essay questions, pose conceptual problems. But many of them are only rote problems, which are not important for organizing documents. Rote problems are the kind of schoolbook exercise you find in many of your textbooks. Rote problems have one right answer, and usually one set routine for arriving at the answer. Most math problems are rote problems. Spelling correctly is a rote problem. Repeating information in a chapter you just read is a rote problem. You never want to organize your documents around a rote problem. THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS The Rhetoric of Problems 107 Frequently Asked Questions 7 P R O B ? “I don’t believe every document has to solve a problem. In my other courses, I write papers that discuss issues rather than solve problems.” You might be right about that. All documents don’t solve problems, just as all documents don’t make points — lists, minutes of meetings, anecdotes, novels, etc. But all documents that make points should normally solve readers’ problems. When you write a paper discussing an issue, you should frame it as a response to a conceptual problem. When you answer a question, frame it as a problem. Academic readers like this, and it will get you far. Remember that you don’t have to use the actual language of problems and solutions in order to frame your papers as responses to problems. You only have to be sure to state a Destabilizing Condition. Usually, you should also state the Consequences of leaving the Condition unresolved. But you can be silent about them if you are certain that they will be obvious to your readers. We recommend, however, that you always articulate Consequences explicitly, even if only to yourself, just to make sure that you really have a problem that your readers will care about. LRS THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA 108 The Rhetoric of Problems Frequently Asked Questions 7 P R O B LR THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LRS S