of Influence Client-Based Subsidies on the Market for Child Care

advertisement

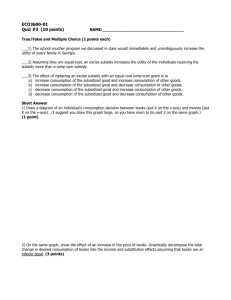

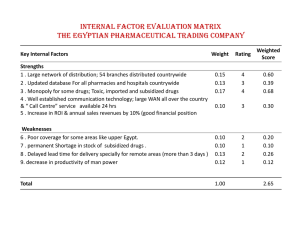

SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 145 PETER R. MUESER AND ROBERT 0. WEAGLEY Influence of Client-Based Subsidies on the Market for Child Care Federal support for child care subsidies targeted to poor households has grown dramatically in recent years. The analysis presented here examines the impact of such subsidies on child care fees charged to aU clients using Missouri data on provider fees and subsidy payments. It is found that patterns for fees and subsidies across providers imply that child care markets are largely competitive. Growth in subsidies observed over the period 1991-1993 increased fees and, by inference, improved quality for subsidized clients. Subsidies also induced an increase in fees for clients not covered by subsidies, an increase most likely due to the cost of expanding the child care market. Implementation of federal legislation has resulted in a dramatic increase in child care subsidies available to low income families.' Moreover, recent welfare reforms have focused on work requirements and lifetime limits on public assistance which increasingly necessitate the provision of child care to low-income families. New federal legislation substitutes block grants for many existing programs and repeals requirements for states to fund early childhood development programs. This means decision making regarding levels 'Most important are the Family Support Act (1988) and the Child Care and Development Block Grant (1990). Peter R. Mueser is Professor, Department of Economics, University of Missouri-Columbia. Robert 0. Weagley is Professor, Department of Consumer and Family Economics, University of Missouri-Columbia. The research reported here was funded in part by the Division of Family Services, Missouri Department of Social Services. Gregory Vadner, Dons Hallford, and George Lauer, at the Division of Family Services, provided assistance in obtaining and interpreting data. Francis Cheung, Rachel Connelly, Michelle Mathews, Michael White, Neil Raymon, and Douglas Wissoker provided useful comments o n earlier drafts of the paper. Sheng-Shyr Cheng provided research assistance. The paper's content and any errors in analysis or interpretationare entirely the responsibility of the authors. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 1995 meetings of the Population Association of America. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 32, No. 1, 1998 0022-0078/O002-145 1.50/0 Copyright 1998 by The American Council on Consumer Interests 146 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS of assistance, in particular child-care, is shifting to the states. States are no longer required to conduct biennial surveys of child care market rates, nor mandated to base their rates of assistance on market rates. On the other hand, federal welfare reform does restrict direct payments to households with children, instituting work requirements and imposing a five-year-lifetime limit on welfare receipt for any household. As single parents receiving welfare face pressure to obtain employment, the need for child care subsidies will grow. Decision makers must think critically about child-care needs of the welfare population, families at risk of entering welfare, and the working poor. There is substantial literature that examines the effects of child care costs and subsidies on the choices made by families (Blau 1991, Culkin, et al. 1991, Kimmel 1992), some research focusing on the market for child care workers (Blau 1992, 1993), and recent research on the long-term benefits to children receiving quality child care (Campbell and Ramey 1993, Kontos 1991). Little work, however, has examined the impact of subsidies on the market for child care and, in particular, no research has focused on the influence of subsidies on the price of child care. The analysis here uses data on fees charged in January 1991 and January 1993 reported by child care providers in Missouri. Over the period 1991-1993, annual subsidies to support child care in Missouri more than doubled to $40 million. We will examine changes in the child care market during that time to infer likely effects of the subsidy program on fees. Until recent changes in the law, subsidy programs in all states had a common basic structure dictated by federal legislation. Now, with states required to develop programs according to their own specifications, information about the incentive effects of various programs is of particular value to state policy makers. The focus will be on subsidies for paid child care provided by nonrelatives outside the child’s home. PREVIOUS STUDIES An extensive amount of literature has examined the impact of child care availability and fees on family employment and child care choices. The decision of whether a woman works may depend on the availability and price of child care, and relative prices for various SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 147 kinds of care strongly influence which will be ch0sen.l Additionally, studies have addressed indicators of child care quality.3 Studies that have examined the impact of government subsidies are more limited. Liebowitz et al. (1992) allowed for variations in the child-care tax credit across states and over time for 1978-1986 and found that high levels of child care tax credits induced women to return to work. Michalopoulos et al. (1992) used variations in tax credits across states as part of a structural model estimating demand for child care services. Their simulations suggested that subsidy increases would induce substantial growth in the use of child care services and would increase expected hours of work for parents. Walker (1992) found that fees for family child care providers receiving government subsidies were higher than for providers who did not receive subsidies. Two studies by Blau focused on the market for child care workers. An analysis across states during the period 1976-1986 (Blau 1992) found that wages for child care workers were not influenced by the levels of child care subsidy. Noting that wages remained almost flat in the face of substantial market growth over this period, Blau suggested that the supply of child care workers was highly elastic. In contrast, a structural model (Blau 1993) estimated modest elasticities of supply in the range from 1.2 to 1.9. None of these studies examined the impact of client-based subsidies, which grew in importance with federal legislative mandates that required subsidies at the 75th percentile of fees found in biennial surveys of child care providers. Although the studies by Blau (1992, 1993) and Walker (1992) included crude measures of subsidy, their analyses did not indicate how growth in these subsidy programs influenced provider fees and quality of care p r ~ v i d e d . ~ The structure of client-based subsidies differs from tax credits. First, only a small portion of households are eligible for client-based subsidies, and they tend to be the poorest households. In contrast, tax credits are available to all families with children in paid care. See Blau (1991); Hofferth and Wissoker (1992);Hotz and Blau (1992);and Kimmel(1992). 3See Arnett (1989); Cost, Quality & Child Outcomes Study Team (1995); Feine (1992); Phillips and Howes (1987); and Whitebook, Howes, and Phillips (1989). 4Blau’sanalyses employed a measure indicating the maximum subsidized fee provided by the state’s child care program but did not include any measure of the number of eligible children nor the size of the state’s budget for subsidy programs. Walker’s analysis merely employed a dummy indicating whether the provider received any government subsidy. 148 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS Second, the structure of client-based subsidies is such that they increase dollar for dollar with child care prices to a state-specified maximum. The impact of such client subsidies on provider prices and, as a result, on non-subsidized consumers may, therefore, differ from that expected for tax-based subsidies. STRUCTURE OF CHILD CARE SUBSIDIES Over the period of our study, Missouri provided direct client subsidies for child care under a variety of programs with a basic structure dictated by federal legislation, which provided a substantial share of the funding. Although eligibility criteria varied across programs, all programs were designed to provide assistance to households with low incomes. No effort was made to provide subsidies to all who met the eligibility criteria. Only those in contact with the Missouri Division of Family Services were evaluated for eligibility, and budget limitations required many eligible households be placed on waiting lists. The state distinguished 27 classes of child care service, based on age of child, hours of care per day, and size of the child care provider. For each of seven geographic areas in the state, a maximum subsidized fee for one day’s care for each class of service was specified. If a provider’s fee was less than this amount the state paid the fee, while if a fee exceeded this maximum, the state paid the maximum and the client was responsible for the difference. Eligible households had their choice of child-care providers. Although the subsidy payment was often made directly to a provider, the subsidy was on behalf of a particular client. Many clients were required to provide a copayment, which depended on family income and number of ~ h i l d r e n .This ~ copayment was a fixed dollar amount per day; it did not depend on the fee charged by the child care provider. While federal guidelines would appear to require that the maximum subsidized fee be at the 75th percentile, prior to November 1991, maximums in Missouri were substantially below average market rates. Following a 1991 survey of child care providers, fee maximums were raised in November 1991 by an average of over 50 ’The term “copayment” is reserved to refer to these payments, excluding payments made by clients to providers charging fees above the maximum subsidized fee. SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 149 percent to accord with market conditions and federal guidelines. These maximum subsidized fees remained in effect through fiscal year 1993. The number of families receiving subsidies also grew over this period, increasing by more than 50 percent between the 1991 and 1993 fiscal years. As a result, child care subsidy payments increased from $19 million in fiscal year 1991 to $40 million in fiscal year 1993. MODELING THE CHILD CARE MARKE’F This section investigates the expected impact of government subsidies on child care fees. The child care market displays characteristics that must be incorporated into the formal model. Child care providers are heterogeneous, and fees differ quite dramatically even within a limited geographic area. To allow for such differences, an unmeasured quality is posited for each provider and will be taken to identify characteristics of the service that clients value. Higher prices, therefore, correspond to higher quality, allowing for the possibility that child care providers with different prices may coexist in a single competitive market. While this definition of quality, capturing unmeasured services valued by customers, is appropriate in our formal model, it is also reasonable to assume that this measure is correlated with professional definitions of quality. Higher quality centers are found t o have better educated and trained teachers with lower rates of employee turnover (Clarke-Stewart , 1992), adequate adult-child ratios, and licensing (Fiene, 1992). This is confirmed by a recent report which defined quality child care as care provided by trained day-care professionals implementing need-based plans for individual children to enhance development of children’s independence. The report concluded that the “cost to providing care is modestly and positively related to the level of quality of services. The additional cost to produce goodquality services compared t o mediocre-quality care was about 10%” (Cost, Quality, and Child Outcomes Study Team, 1995, 7). In the following sections, we spell out the implications of two models. The first assumes that the child care market is perfectly competitive, and the second that providers have monopoly power. The empirical analysis that follows will attempt to determine which model 6A more detailed treatment of the models presented in this section is available from the authors. 150 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS best explains pricing patterns observed in child care markets. Distinguishing between these models is important for determining the effects of child care subsidies. The sections that follow use this knowledge of the child care market to interpret data regarding the impacts of child care subsidies. For both models, it is useful to specify a common notation to describe the subsidy structure. The state-specified maximum subsidized fee will be denoted p*. If the provider’s fee, p, is less than p*, then the state pays p. As the client, i, must make a copayrrrent of mi, which varies by income and family size, the effective subsidy for this client is si = p - mi; the effective cost to the client is mi. If p equals or exceeds p*, the state pays the provider p*, so the effective subsidy is p* - mi; the cost to the subsidized client is then p - p* + mi. Competition Perfect competition is consistent with the observation that entry into the child care industry is easy, and customers frequently have a choice between multiple providers. In the model, perfect competition does not require that providers offer the same level of quality, only that customers identify quality that prompts them to patronize a particular supplier. Under perfect competition, clients can choose among child care providers in a given market according to the desirability of the pricequality mix offered. Competition implies price is equal to marginal cost, and there is a market quality-price locus, p(q). Each consumer chooses a level of quality that maximizes a utility which incorporates both quantity and quality of care. With variation across households in both the importance of quality and characteristics that are perceived as quality, there will be a dispersion of prices reflecting the cost of producing and demand for different levels of quality. Consider a subsidy-eligible household that would, in the absence of the subsidy, choose a level of quality (q) such that p(q) is less than p* (Figure 1). The choice is given by the point on the curve p(q) which maximizes utility. Noting that preferred combinations involve lower prices and higher quality, the point of tangency between the indifference curve and p(q) identifies the choice (p,,,qo). The subsidy program replaces the price function with the single copayment mb which is independent of quality up to the quality level q*. The effective opportunity locus is, therefore, a horizontal line to q*, at which SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 151 FIGURE 1 Consumer Decisions Under Perfect Competition P' Po Price Quality Yo 4* point it slopes up parallel to p(q). The optimum on this locus will be at a higher quality level, q*, such that p(q*) = p*, identified by utility level Uz.Hence, while the subsidy allows the household to purchase services at price mi, the provider receives price p* for any subsidized household that would otherwise choose a lower price (and lower quality) service. For a subsidized household originally choosing quality such that p(q) >p*, Figure 1 makes clear that although quality may shift on the new budget line, the impact is more modest, depending on substitution and income effects. For any client receiving the subsidy, there will also be an increase in the quantity consumed due to the decline in the per unit price. Monopoly Some observers have questioned the competitiveness of the childcare market (Walker 1991). Quality may not be fully observable and information about providers may be difficult to obtain. Of parents 152 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS patronizing child care providers, approximately three of four report learning about the provider through informal channels, such as personal referrals or direct acquaintance (Walker 1991). If search costs are high enough or customers are able to obtain information about a limited number of providers, each provider may exercise some level of local monopoly power. The second model examines the market in the case of a simple monopoly. In the monopoly model, the provider chooses both price and quality. Consider a standard monopoly model where the provider chooses price, p, and the quality level, q, producing quantity level, y, to maximize profits: We take y = Zyi, where y i = y i p - sbq), household i’s demand is assumed to be decreasing in p- si (price net of the subsidy) and increasing in q. C(y,q) is a conventional cost function c y> 0, c m > 0, and cq >O. The provider is assumed not to discriminate among clients in fees or quality. The average per unit subsidy is defined as S = c&yi/cyi. Price decisions of the monopolist can be illustrated in a simplified structure provided in Figure 2, which ignores quality. Curve AB indicates a demand curve in the absence of any subsidy, and the curve CDB illustrates a possible curve where some of the monopolist’s clients are eligible for the subsidy. The subsidy causes the curve to shift up and to the right, and to have a kink at the maximum subsidized fee, p*. The per unit subsidy is constant when the price is above that level but varies directly with the price at lower prices. The marginal revenue curve MR is the curve associated with this subsidized demand, so the profit maximizing quantity corresponds to the point where MR crosses the firm’s marginal cost curve. The firm’s response to a change in the subsidy depends on the price the firm is charging. The portion of the subsidized curve indicating demand below p* becomes steeper and moves to the right as the proportion of subsidized clients increases. Using this result, if the firm chooses a price below p* (as it does when it faces the marginal cost curve MC $, the firm’s response to an increase in the proportion eligible for subsidies is always to increase prices (dp/dS >O). Of course, a change in the p* has no effect on such a firm, because this has no effect on the relevant portion of curve DB. SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 153 FIGURE 2 Monopolist’s Decision Price P* Quantity \ B If the price is set at p*, as it is when the marginal cost curve is M C , it is clear that, over some range, an increase in p* will cause a lockstep increase in optimal p (dp/dp* = 1). In contrast, an increase in the proportion subsidized (p*) may have no effect on the price choice, but there are conditions under which such a firm will respond to such an increase by raising p to a level above p*. It is easy to show that subsidy growth cannot cause the firm to reduce its price. Finally, consider the case where the firm chooses a price above p*. The firm’s response to an increase in the subsidy level, due either to an increase in p* or an increase in the number of eligible households, is indeterminate. An increase in p* or the proportion subsidized have similar effects on CD, the part of the demand curve above p*. The slope of this portion of the curve depends on the particular demand characteristics of those who are subsidized. As only low income households are eligible for child care subsidies, their demand elasticity may be great. Subsidies to this group may cause the slope of CD 154 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS to decline in absolute value, which can cause a decline in the price chosen by the monopolist. The provider also chooses quality. When p is less than p*, the subsidy will create incentives for subsidized clients to choose higher levels of quality. As a result, the monopolist will increase quality as the proportion of clients subsidized increases. Effects on quality are ambiguous where the provider charges over p*. Although these results are similar to those in the competitive model, they differ in several important respects. Both models predict increases in quality for customers originally paying fees below p*. However, in the competitive model all fee growth corresponds to an increase in quality, while part of fee growth for the monopolist reflects growth in the provider’s profit margin as customers become less price sensitive. For customers in a competitive market who would pay less than fee p*, the impact of subsidy eligibility is to raise the fee to p*, a much larger impact than predicted by the monopoly model. DATA AND ANALYSIS The data consist of information on child care fees in January 1991 and January 1993 based on responses by child care providers in Missouri to two mail surveys administered by the Division of Family Services. Respondents specified their fees on a daily basis for each category of child care provided, with categories defined by age of child and hours of care per day.’ In addition to fee information, respondents in the 1993 survey indicated the number of children served in each age range. Questionnaires for the first survey were mailed in December 1990 to all 3,272 licensed child care providers in the state and to 659 unlicensed providers. completed responses were obtained from 1,909 (58.3 percent) licensed providers and 183 (27.8 percent) unlicensed providers. Questionnaires for the second survey were mailed in December 1992 to 3,629 licensed providers and 621 unlicensed providers. Completed responses were obtained from 2,45 1 (67.5 percent) licensed providers and 213 (34.3 percent) unlicensed providers. ‘Reported fees include all payments made for a specified service, gross of any subsidy. State regulations require that fees for subsidized and unsubsidized clients be the same. sSome unlicensed providers chose t o register with the state for various reasons. As unlicensed providers are eligible for subsidies, these providers were included in the survey. SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 155 Providers serving fewer than five children or those with religious affiliations are not required to be licensed in Missouri. Other data suggest that fewer than half of the state's child care providers are actually licensed, so the sample is not representative of the population of providers. Furthermore, it is possible that providers systematically misrepresent their fees. Previous work suggests many clients are given substantial discounts (Nelson 1990), and these may not be reflected in reported fees. To investigate these issues, a random telephone survey of households in Missouri was conducted in the fall of 1993, asking respondents who had used child care to indicate fees they paid the previous January. These responses were then compared with average fees that child care providers reported charging in January, where the latter were averaged for seven geographic areas within the state, and distinguished by class of service. Average fees reported by households differed from fees reported by providers by less than five percent. This difference was not statistically significant. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume provider reports give a reasonable measure of client fees actually paid. l o In addition to provider fee reports, state records were obtained for the number of subsidized clients for whom providers received direct payments during the periods July 1990 to June 1991 and July 1992 through June 1993. Payments made directly to clients could not be traced. Approximately five percent of total payments were made directly to clients in the first period, while in the second period it was 20 percent. Plan of Analysb Table 1 displays average reported fees for each category of care for both January 1991 and 1993, as well as the percentage increase in fees. While the cost of full-day care for preschoolers increased 6.6 percent over the two-year period, part-time day care for preschool children increased over 33 percent. Costs of the other categories of 'Households with at least one child age eleven or under responded regarding child care arrangements for a total of 284 children. Of these, 119 had paid child care fees, and 71 had usable dollar estimates of child care rates. '"Details of the Missouri household survey are found in Mueser and Weagley (1993). 156 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS TABLE 1 Average Reported Daily Feesain Dollars for 1991, 1993, and Rate of Growth All Respondents Measure Mean Dollars St. Dev. 11.67 12.44 6.6 4.99 7.41 8.17 10.3 Selected Sample Mean Dollars St. Dev. Nb 1436 1920 11.69 12.70 8.6 5.12 8.08 743 756 4.13 4.15 978 1175 7.46 8.18 9.7 4.37 3.99 496 456 4.35 5.70 31.0 2.97 3.29 775 973 4.43 5.79 30.7 3.09 3.74 3 88 357 10.47 11.13 6.3 3.84 3.83 1848 2418 10.48 11.21 7.0 3.72 3.74 95 5 689 6.79 7.61 12.2 3.40 3.29 1355 1646 6.88 7.58 10.2 3.74 3.21 689 639 4.01 5.36 33.7 2.30 2.80 1014 1275 4.06 5.35 31.8 2.38 3.09 518 473 9.30 10.34 11.2 3.48 3.52 1558 1969 9.40 10.28 9.4 3.33 3.20 754 760 6.41 7.19 12.2 2.98 3.05 1309 1623 6.42 7.11 10.7 3.16 2.58 625 619 3.79 5.05 33.2 2.07 3.38 1145 1499 3.77 4.83 28.1 2.04 2.42 547 560 Nb Infanr Full day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Half day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Part day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Preschool Full day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Half day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Part day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) School Age Full day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Half day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) Part day care 1991 1993 Rate of growth (Yo) 5.13 (continued on next page) SUMMER 1998 157 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 TABLE 1 (continued) Selected Sample All Respondents Mean Dollars Measure St. Dev. Nb NA NA Mean Dollars St. Dev. Nb Composite Fee 1991 1993 Rate of growth NA (070) 9.87 10.68 8.2 4.18 4.14 1007 1007 a“Full day” is 5 or more hours, “half day” 3 to 5 hours, and “part day” less than 3 hours. kifferences in the Ns indicate where a category of care was not offered in both periods. care increased at rates somewhere between these two extremes. During this period the Consumer Price Index increased 7.3 percent. In examining what role the growth in subsidies may have played in fee growth, two paths of influence are of concern. First, subsidies may increase overall demand for child care services. If the supply of inputs is not perfectly elastic so that the aggregate supply curve of child care services is upward sloping, prices in the market will increase. Even where firms have monopoly power, such aggregate effects will occur if they do not control the market for the input. In the analysis, measures of subsidy at the level of the county are available. Any market level effect of the subsidy should influence all providers in the relevant market due to a shift in the demand curve, without regard to differences in the number of subsidized clients served . There will also be differences across providers in fees charged depending on the number of subsidized clients served. The expected relationship between subsidy and fee differs according to the structure of the child care market. If the child care market is competitive, the theory focuses on individual consumer decisions regarding quality (and thus price). Those eligible for subsidies would have no incentive to patronize a provider charging less than p*, the maximum subsidized fee. Those who would choose lower-priced providers, in the absence of the subsidy, patronize a provider charging exactly p*. Looking across providers, this selection suggests a complex relationship between the proportion of subsidized clients served by a provider and fees charged. Figure 3 illustrates the expected distribution of providers according to the proportion of clients receiving subsidies. 158 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS FIGURE 3 Expected Distribution of Providers by Proportion of Clients Subsidized X X X X X x x X X I1 x X X X X X X X X X X X I X X X x P* x I11 x x x x x X X X X x x x x X x X X Provider Fee x X X X X X X X 0 Proportion Subsidized -> 1 Among providers who have no subsidized clients, some will charge fees below p*, and some above p*, whereas those with any subsidized clients never charge fees below p*. As a result, the average fee charged by providers with no subsidized clients is expected to be below that of providers with some subsidized clients. However, among providers serving some subsidized clients, greater subsidy will be associated with lower fees. The reason is that there will be a large number of subsidized clients who wish to choose a provider charging exactly p*. To accommodate them, providers with larger numbers of subsidized clients will be very likely to charge p*. On the other hand, SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 159 providers with smaller numbers of subsidized clients may well charge higher fees, reflecting quality levels which are attractive to relatively few subsidized clients. In contrast, for a monopolistic provider, the number of subsidized clients in its market is exogenous. If the monopolist's fee is below the maximum subsidized fee, p*, an increase in the number of subsidized clients will increase the fee it charges. If the fee is initially above p*, the impact is indeterminate. To test these theoretical relationships, a model that predicts the fee charged by each provider as a function of the proportion of clients who are subsidized, the proportion of the total county day-care population who received a subsidy, and other provider and county characteristics was fit. Each of the variables will be discussed. To measure the relationship between subsidies and fees at the provider level, the total number of clients the provider received direct reimbursement for was divided by the total number of child days of care provided. As noted above, the hypothesized relationship between this variable and fees depends on whether the market is competitive or monopolistic. l 1 In contrast to the subsidy at the provider level, the measure of county subsidy is exogenous to the provider's fee. Hence, the effect of this measure may reflect a causal relationship between subsidy payments and child care pricing. The variable to measure this market level effect was the number of individuals in a county who received direct reimbursement divided by published estimates of the total number of children needing care as of 1990. The greater the proportion of population receiving direct subsidy payments, the greater the expected price of day-care, as clients purchase greater quantities of day-care due to receipt of the subsidy. Other provider and county level data were also included in the estimated equations as control variables. The total number of children reported to actually be in the care of the provider was included to control for economies of scale in the production of services. Therefore, its effect is expected to be negative. To control for type of care "It should be stressed that the relationship between number of subsidized clients and fee charged by a provider does not identify a causal relationship, as, in the competitive model, it is a result of selection of providers by clients. However, the estimates of this model are used to examine the extent to which subsidized clients pay fees that differ from unsubsidized clients, controlling for market and provider characteristics. 160 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS being provided, the number of infants and the number of preschool children were included as regressors. Given that the omitted category is the number of school aged children, ceteris paribus, it is expected that larger numbers of children in each of the younger aged categories will positively affect the estimated composite fee. To control for the effect of the formal classification of the daycare provider on the maximum subsidized fee, dummy-variables for each provider’s classification were included. The omitted category was “family home,” while “group home” and “day-care center’’ were the included categories. As each of these latter classifications represent categories of care with increasing maximum subsidized fee, with number of children actually receiving care being held constant, the expected sign on each of these dummy variables is positive. Two variables were included to control for possible cost function factors. In Missouri, day-care providers must be licensed if they serve at least five children and are not sponsored by a religious organization. It is expected that many non-religious, smaller-size care providers may involve less formal arrangements. l2 Variables to control for possible cost factors were a dummy variable for licensed day care, with an expected positive effect to reflect greater per unit cost of care, and a dummy variable for minority owned, to reflect possible interactions among ownership and customer base. Median county household income in 1989 was used in the empirical model as a proxy for household income. Quality day care is posited to be a norqal good and the expected sign on median income is positive. The number of AFDC recipients as a percentage of those under age 18 in each county was entered as a control for a variety of social and economic factors influencing the local environment. The variable is highly correlated with the amount of child-care subsidy payments to residents in a county. Models with the variable present will have to be interpreted carefully. Other county variables were included to control for the effect of recent economic change and demographic structure in the larger market. The following variables are expected to positively affect daycare fees: percentage change in county employment over 1980-90, 12A survey of Missouri parents found that 36 percent of all care is being provided by relatives, 22 percent by babysitters, 14 percent by child-care centers, and 29 percent by other arrangements. The percentage of children cared for in centers was found to be directly proportional to parental income (Klein et al., 1993). SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 161 percentage of the population in 1990 with 12 or more years of education, percentage of workers who commuted outside of the county of residence in 1990, county labor force participation rates of mothers with children under the age of six, estimated total number of children under the age of six divided by the total population, and the logarithm of the county population in 1990. Comparison between the two periods will be critical to infer the impact of the subsidy. Models using a sample of providers who responded to both surveys were estimated. Each survey asked providers to identify fees for nine classes of service; however, many respondents omitted some classes of service, presumably because they did not offer them. To prevent differential response in the two periods from influencing results, consideration was limited to those classes of service for which fees were reported in both periods. Data do not allow one to determine the class of service received by a subsidized client. As a result, a single composite measure of each provider’s fees was constructed. Using classes of service for which fees were reported in both periods, a composite fee defined as a weighted average of the fees charged for the various classes of service was computed. Fees in each age category were weighted by the proportion of children the provider reported in that category, and fees for different numbers of hours were weighted to approximate the proportion of children receiving each type of care, as indicated by a survey of Missouri households (see notes to Table 2). As each provider’s fee composite is based on a different set of reported fees, differences among providers due to differences in classes of service reported are controlled by a set of eight variables (class of service controls) to capture differences in fees for the nine classes of service. Each variable indicates the proportional weighting used to construct each provider’s composite fee measure. As such, its coefficient can be interpreted as the (log) difference between the predicted fee for that service and the omitted fee class (preschool fulltime care). Effect of Nonresponse To be in the analysis, a provider had t o report fees in both surveys for at least one class of service and valid data on other variables. Fees were eliminted which exhibited implausibly large changes between 0.061 0.089 1991 1993 1993 1993 1993 0.118 0.276 Proportion of subsidized served by provider: Number of clients for which the provider received reimbursement divided by the number of children reported in care in 1993. Where this value exceeded one, it was truncated to one. Proportion subsidized in county: Number of individuals receiving direct subsidies from all providers in the county in fiscal year divided by an estimate of the total number of children needing care in 1990 (see below). Proportion of composite fee attributed to service type: Infant-Full day Half day Part day Preschool-Full day Half day Part day School age-Full day Half day Part day Total number of children reported in provider’s care Total number of infants reported in provider’s care Total number of preschool children reported in provider’s care 1 if provider classified as “day care center” 1 if provider classified as “group home”c 1 if provider minority owned 1991 1993 1991 1993 Logarithm of the composite fee charged by the providera 33.958 6.395 20.096 0.449 0.162 0.364 2,513 3,494 3,494 3,494 3,494 3,494 ~ 35.601 8.530 22.861 0.447 0.162 0.356 0.043 0.053 0.372 0.356 0.359 0.348 ~ 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 N (continued on next page) 28.060 2.574 11.709 0.280 0.027 0.157 0.062 0.090 0.006 0.003 0.54.4 0.025 0.014 0.125 0.063 0.053 30.997 3.929 18.0% 0.275 0.027 0.159 3,479 3,479 2,513 2,513 0.166 0.044 0.055 0.25 1 0.355 2.217 2.304 0.255 0.275 Mean NA NA N St. Dev. Mean St. Dev. Year Selected Sample All Respondents Variable TABLE 2 Variable Definitions and Descriptive Statistics 1990 1990 1990 1989 Year 0.198 0.235 0.121 0.041 0.059 0.015 3,494 3,494 3,494 0.184 0.218 0.126 0.035 0.050 0.016 0.221 0.052 0.215 0.048 1.492 0.427 3,494 3,494 0.392 0.190 11.543 0.239 6.737 0.266 9.588 6,873 26.791 9.029 16.556 0.007 0.402 3,492 3,494 1.533 0.440 11.567 0.262 67.309 0.924 11.894 26,163 25.247 73.870 27.540 0.052 0.203 3,479 2,427 3,476 3,476 3,476 3,476 3,476 3,479 6.633 0.265 9.491 7,053 27.416 8.888 16.203 0.007 66.879 0.924 11.939 26,242 25.921 73.780 28.185 0.052 Mean ~ N ~ _ 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 1,007 St. Dev. N St. Dev. Mean Selected Sample All Respondents aProviders were asked to report fees for nine classes of service, based on age of child (infant, preschool, school age) and number of hours per day (5 or more, 3 to 5 , less than 3). For each age group, a weighted average based on the proportion of children in each category of hours in the Missouri household survey was constructed (infants, .90, .05, .05; preschool, .90, .05, .05; school age, .45, .30, .25). These age-specific fees were then weighted by the number of children that the provider reported serving in each age category to produce the composite fee. The procedure was modified to omit any fee category that the provider failed to report in either period, with weighting adjusted to reflect such omissions. Hence, a particular provider’s composite fees for both periods are based on the same classes of service, but across providers the composite may be based on different classes of service. ”sum of the number of infants, preschool children, and school age children reported by provider. Troviders are classified as “center,” “group home,” or “family home,” with the categorization corresponding approximately to number of children served ( >20, 10-20, < 10). The classification influences the maximum subsidized fee. dData are based on 1990 U.S. census reports as compiled in Office of Socioeconomic Data Analysis (1992). Qmitted category comprises all counties outside metropolitan areas (98 counties). 1 if provider licensed AFDC recipients as a percentage of those under age of 18 in the countyC Median county household income (dollars) Percentage change in county employment, 1980-90 Percentage of the county population with 12 or more years of education Percentage of county workers commuting Estimated total number of children under the age of 6 needing care in the county in 1990, based on number of children with working mothers, divided by total population County labor force participation rate of mothers with children under the age of 6 Logarithm of county total population in 1990 1 if county is in St. Louis metropolitan area (Jefferson, Franklin, St. Charles, and St. Louis counties and St. Louis city)e 1 if county is in Kansas City metropolitan area (Jackson, Cass, Clay, Lafayette, Platte, and Ray counties) 1 if county is in Springfield metropolitan area (Greene and Christian counties) 1 if county is in Joplin metropolitan area (Jasper and Newton counties)e 1 if county is in Columbia metropolitan area (Boone county) 1 if county is in St. Joseph metropolitan area (Buchanan county) Variable TABLE 2 (continued) _ ;j; w e 5 N c P c 00 W 5 P 164 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS the surveys. l3 The “Selected Sample’’ in Tables 1 and 2 identifies the subsample of providers employed in the analysis. Average fees charged per day of care, reported in Table 1, differ by relatively little for the full sample and the selected sample. In contrast, average values for several independent variables, reported in Table 2, differ substantially. The most important difference is the proportion of subsidized clients in the 1991 fiscal year. In the full sample, for the average provider, 11.8 percent of clients received a subsidy, while in the selected sample, the figure was over 25 percent. This difference suggests that providers with more subsidized clients in 1991 were much more likely to respond to the survey in 1991. Table 2 suggests there is virtually no difference in the proportion of subsidized clients in 1993 between the full and selected sample. However, this is an artifact of variable construction. Number of children served by a provider is available only for providers who responded to the 1993 survey, so proportion of subsidized clients in 1993 is available for those responding to the 1993 survey. Thus, even in the “full sample” the reported mean is based on those who responded to the 1993 survey. Other differences between the selected and the full sample statistics are much smaller. Providers in the selected sample serve an average of 31 children, rather than 28 in the full sample. The distribution of the selected sample across geographic areas is very similar to that of providers in the full sample, so too are measures reflecting county characteristics. Relationship Between Subsidies and Fees Table 3 presents simple regression equations predicting the logarithm of composite fees for 1991 and 1993. Two variables are used to capture the relationship between the number of subsidized clients served by a provider and fees charged: a dummy variable which identifies providers serving no subsidized clients and a continuous measure of the proportion of clients who received subsidies. In both periods, estimated coefficients indicate a relationship consistent with the basic structure suggested by the competitive model. The negative “Initial inspection of fee reports revealed cases where it appeared that fees were reported on an hourly rather than a daily basis. Fees which changed by more than $20, or by more than a factor of two were omitted. The basic results were not substantially changed by this selection. SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 165 TABLE 3 Model 1: Basic Equation Predicting Child Care Fees Dependent Variables ~ Independent Variables Log 1991 Fees t Log 1993 Fees ~ Intercept Proportion subsidized served by provider (1991, 1993) 1 if no subsidized clients served by provider (1991, 1993) Proportion of composite fee attributed to class of service: Full day infant Half day infant Part day infant Half day preschool Part day preschool Full day school age Half day school age Part day school age Proportion subsidized in county (1991, 1993) Adjusted R 2 t ~ 2.4%9 -0.258 1 -6.3 2.4550 -0.1166 -3.0 -0.1823 -6.6 -0.1209 -4.7 0.2205 -0.1102 -0.3312 -0.3230 -0.8943 -0.2799 -0.6681 -1.1271 -0.03 73 3.9 -0.3 -0.5 -2.5 -5.4 -4.0 -8.0 -14.6 -0.2 0.1960 -0.2375 -0.221 7 -0.2066 -0.7758 -0.2621 -0.6758 -1.0804 -0.55440 3.6 -0.7 -0.3 -1.7 -4.9 -3.9 -8.4 -14.5 2.9 0.3077 0.3053 coefficient estimated for no subsidized clients indicates such providers have lower fees than providers with small numbers of subsidized clients. Returning to Figure 3 , this is due to the fact that providers charging less than the maximum subsidized fee are predicted to serve no subsidized clients, which reduces the average fee of providers with no subsidies (labeled as I, Figure 3) to below that for subsidized providers (11). The negative coefficient on the proportion of clients who are subsidized implies that as providers increase the proportion of subsidized clients, fees decline (e.g., from I1 to 111). The competitive model predicts this pattern, as providers charging fees very close to the maximum subsidized fee are expected to have larger proportions of subsidized clients. The above pattern is not consistent with predictions of the monopoly model. Although the monopoly model implies that fees increase with the proportion of subsidized clients, it does not predict a discontinuity at zero. The square of the proportion of subsidized clients was not statistically significant when added to any of the reported models, allowing us to reject the conjecture that the impact of the dummy variable is merely picking up a continuous nonlinearity in the relationship involving the proportion of subsidized clients. The sig- 166 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS TABLE 4 Model 2: Equation Predicting Child Care Fees Controlling Provider and County Characteristics Dependent Variables Log Log Independent Variables 1991 Fees t 1993 Fees t Intercept Proportion subsidized served by provider 1.0782 -0.0761 -2.5 1.1762 -0.0040 -0.2 (1991,1993) 1 if no subsidized clients (1991,1993) Proportion subsidized in county -0.0639 0.2948 -3.1 -0.0224 0.0110 -1.3 1.0 -0.0007 0.0087 0.0027 0.0870 0.0694 -0.1064 0.0193 0.0065 -0.9 7.2 2.8 3.8 1.6 -4.8 0.6 3.0 -0.0003 0.0079 0.0021 0.1092 0.0786 -0.0260 0.0735 0.0074 -0.5 7.3 2.4 5.4 2.1 -1.3 2.6 3.6 3.0 0.6 3.9 -0.0002 0.0081 3.0 -0.3 4.7 -0.0006 -0.0029 -0.6 -1.5 -0.0013 -0.0035 -1.6 -2.1 0.5032 0.0346 0.3 2.0 2.4231 0.0158 1.6 1.0 0.1 (1991,1993) Total number of children in provider’s care Total number of infants in care Total number of preschool children in care 1 if “day care center” 1 if “group home” 1 if minority owned 1 if licensed AFDC recipients as percent of under 18 years County median household income Percentage change in employment, 1980-90 Percentage of county adults with 12+ years education Percentage of county workers commuting County labor force participation rate of mothers with child <6 Estimated under 6 population needing care Logarithm of county population Class of service Dummy variables for region Adjusted R2 o.ooo012 0.0003 0.0071 o.oooo11 Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled 0.6879 0.7295 nificance of not serving subsidized clients, consistent with the competitive theory, suggests that there is a true discontinuity in the relationship. The proportion subsidized in the county was found to have a nonsignificant coefficient in the first period and a positive, significant coefficient in the second period. The positive coefficient implies that providers in counties with larger proportions of subsidized clients have higher fees. Estimates in Table 3 control none of the characteristics of the child care provider or the local market. Table 4 presents estimates for an equation that controls for seven additional characteristics of the provider, seven socioeconomic characteristics of the county, as well as six dummy variables for differences between seven regions in the SUMMER 1998 167 VOLUME 32,NUMBER 1 state. With these other variables controlled, effects of the proportion of subsidized clients served by the provider are much the same, although effects are generally smaller, and they are not statistically significant in the second period. With these additional controls, the effect of the proportion receiving subsidy in the county is not statistically significant in either period. A single variable is responsible for this nonsignificance, the density of AFDC recipients in the county. Table 5 reports results where the AFDC measure is omitted. The coefficient of the county subsidy measure is statistically significant in predicting fees in each period. The interpretation of this result is discussed below. Table 6 reports three estimates of lag adjustment formulations, which parallel the specifications for 1993 but include the 1991 fee as an independent variable. The coefficient on the lagged variable in the TABLE 5 Model 3: Equation Predicting Child Care Fees Controlling Provider and County Characteristics but Omitting AFDC Dependent Variables Log Log Independent Variables 1991 Fees t 1993 Fees Intercept Proportion subsidized served by provider 1.1235 -0.0725 -2.4 1.2970 -0.0002 -0.0 -0.0618 0.7650 -3.0 3.2 -0.0207 0.4861 -1.2 2.8 -0.OOO6 0.0088 0.0026 0.0913 0.0636 -0.0949 0.0211 0.000007 -0.0001 0.0053 -0.9 7.2 2.7 4.0 1.5 -4.3 0.7 2.0 -0.2 3.0 -0.0003 0.0079 0.0020 0.1131 0.0662 -0.0153 0.0745 O.ooo007 -0.0007 0.0053 -0.4 7.3 2.3 5.5 1.7 -0.8 2.6 2.0 -1.6 3.4 -0.0001 -0.0040 0.2 -2.2 -0.0007 -0 .W48 -0.9 -2.9 1.6959 0.0555 1 .o 3.5 3.4662 0.0379 2.3 2.7 t - (1991,1993) 1 if no subsidized clients (1991,1993) Proportion subsidized in county (1991,1993) Total number of children in provider’s care Total number of infants in care Total number of preschool in care 1 if “day care center” 1 if “group home” 1 if minority owned 1 if licensed County median household income Percentage change in employment, 1980-90 Percentage of county with 12+ years education Percentage of county workers commuting County labor force participation rate of mothers with child <6 Estimated under 6 population needing care Logarithm of county population Class of service Dummy variables for region Adjusted R’ Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled 0.6853 0.7262 168 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS TABLE 6 Equations Predicting the Logarithm of the 1993 Composite Child Care Fees with Lagged Fee Independent Variable Intercept Proportion subsidized served 1 if no subsidized clients 1993 Proportion subsidized in county, 1993 Logarithm of 1991 composite fee AFDC recipients as percent of under 18 years Class of service Dummy variables for region Adjusted R’ Coefficient t Coefficient t Coefficient t 0.4189 0.04156 -0.0053 0.2393 2.3 -0.4 2.7 0.4998 0.0186 -0.0023 -0.0078 1.0 -0.2 -0.1 0.5344 0.0199 -0.0016 0.1576 1.1 -0.1 1.4 0.8414 60.6 0.6612 34.8 0.6645 35.1 0.0024 1.7 0.8520 Controlled Controlled Controlled Controlled 0.8792 0.8790 second and third equations suggests that a third of the adjustment toward equilibrium occurs in the two years between periods. Several coefficients differ substantially from those reported in the previous equations. The coefficient of proportion subsidized served by the provider is positive and for providers with no subsidized clients in 1993 is essentially zero. Hence, in the two-year period, providers with large proportions of subsidized clients exhibited faster fee growth, although the coefficient is not statistically significant. The coefficient of the proportion receiving subsidies in the county shows a positive relationship, although it disappears when AFDC participation is included (column 2). Relative Growth of Fees for Subsidized Clients While care must be exercised in identifying causal relations, it is useful to examine how fees paid by subsidized and unsubsidized clients changed between the two periods. A simple measure of change in relative fees may be obtained by weighting fees charged by each provider by the number of subsidized and unsubsidized children served and summing across providers. Because the composite is based on a different class of service for each provider, it is necessary to correct reported composite fees for variations in class of service. Results are reported in panel A of Table 7, which report differences in the logarithms of fees. Line 1 of panel A shows that in 1991, fees for subsidized clients were about 12 percent lower than fees for com- SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 169 TABLE 7 Logarithm of Ratio of Subsidized to Unsubsidized Child Care Fees Panel A a Controlling for class of service only (1) (2) (3) (4) 1991 fees, 1991 fees, 1993 fees, 1993 fees, 1991 subsidy counts (observed) 1993 subsidy counts 1991 subsidy counts 1993 subsidy counts (observed) -0.1238 -0.0686 -0.0760 -0.0272 0.0552 0.0478 0.0966 Panel B Controlling for class of service, provider characteristics, and county characteristics (1) 1991 fees, 1991 subsidy counts (observed) (2) 1991 fees, 1993 subsidy counts (3) 1993 fees, 1991 subsidy counts (4) 1993 fees, 1993 subsidy counts (observed) -0.0229 -0.0183 -0.0075 -0.0002 0.01 16 0.0224 0.0297 ~ Key Tomposite fees for 1991 and 1993 for each provider i are corrected usingcoefficients of variables for the proportion of the composite fee attributed to each service type: full day, half day, and part day-infant; full day, half day, and part day-preschool; and full day, half day, and part day-school aged; as estimated in an equation similar to that in model 1, omitting the variable measuring the proportion of the county day care population receiving a subsidy payment. komposite fees 1991 and 1993 are corrected using all coefficients in model 2. Row 1 column a: EiN9l:ln(P9li) - CiN91iUln(P91i) Row 2 column a: EiN93:ln(P91i) - CiN93Yln(P9li) Row 3 column a: EIN91;ln(P93i) - CiN9IiUln(P93i) Row 4 column a: EiN93:ln(P93i) - CiN93i"ln(P93i) N91iS,N93:, number of subsidized clients served by provider i in 1991, 1993. N91;, N93?, number of unsubsidized clients served by provider i in 1991, 1993. P9Ii, P93i corrected composite fee charge by provider i in 1991, 1993. Column b: Difference from row 1. parable service for unsubsidized clients. Line 4, column a, indicates that two years later this gap had declined to less than three percent. This implies that the relative fees of subsidized clients increased by nearly ten percent (column b). This shift is due both to an increase in the number of subsidized clients served by higher fee providers and by an increase in fees charged by providers already serving subsidized clients. Lines 2 and 3 provide an indication of the relative importance of these two effects. Line 2 indicates that, if fees had remained unchanged, the shift in subsidized clients across providers would have caused the gap between unsubsidized and subsidized clients to decline from 0.1238 to 0.0686 or by 0.0552. In contrast, if changes in fees between 1991 and 1993 had occurred with no shift in the numbers of 170 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS subsidized clients served by each provider, the gap would have declined to 0.0760 or by 0.0478. It can be concluded that, over this two-year period, fees increased faster for providers serving subsidized clients, but that this effect was less important than increases in numbers of subsidized clients served by higher fee providers. The above clearly supports the view that the increased subsidies allowed clients to choose higher priced and very likely higher quality providers. A provider’s quality shifts slowly, as higher staff-to-child ratios, increased staff education, and administrators’ experience (Cost, Quality & Child Outcomes Study Team, 1995) take time to achieve. This implies increases in the quality of care demanded would occur largely in the form of movements toward providers already providing quality care. Panel B performs a similar exercise but controls for provider and county characteristics available in the data. Given that quality differences are controlled by these variables, differences observed in panel A will be reduced. Row 1 indicates that such controls reduce the gap between unsubsidized and subsidized clients to two percent in 1991, and that there is no observed gap in 1993. These results help confirm that observed differences between subsidized and unsubsidized clients reflect quality differentials captured by the provider and county control variables. Even with controls, changes in the allocation of subsidized clients across providers account for about a third of the shift over two years, while changes in fees across providers account for two-thirds. This provides limited support for the view that growth in subsidies has allowed subsidized providers to increase fees faster than others. Of course, the two percent growth attributed t o such fee increases may also reflect unmeasured quality improvements for providers serving subsidized clients. Finally, results in Table 7 allow us t o reject claims that subsidized clients pay appreciably more than others. While subsidized clients may well pay fees above those they would pay in the absence of the subsidy, such effects merely put them on a par with unsubsidized clients. As this permits subsidized clients t o obtain quality similar to other clients-a view the analyses support-there appears to be appreciable social benefits t o the subsidy program. Improvements in the cognitive development of children who receive subsidies, associated with higher fees, may be particularly valuable. The monopoly model suggests that subsidies would cause pro- SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 171 viders with large and growing numbers of subsidized clients to increase fees. The evidence implies that observed growth in subsidized fees is not, for the most part, due to responses by monopolistic providers. The small predicted growth in subsidized fees, once provider and market characteristics are controlled, argues against empirical importance of a monopoly in this market. Growth of Fees in Subsidized Markets If supply curves for factors used in producing child care services are upward sloping, providers in factor markets with greater child care demand should charge higher fees. The proportion of children in the county who receive subsidies should cause a demand shift. If this causal path is important, subsidies could raise child care fees even for those providers who serve no subsidized clients. In the model 1 specification (Table 3), in which provider and county characteristics are not controlled, the coefficient of the county subsidy measure is not statistically significant in the first period but is positive and significant in the second. In model 2 (Table 4), which controls for provider and county characteristics, the coefficient is not statistically significant in either period. Model 3 estimates (Table 5) show that, if the single variable indicating the level of AFDC participation in the county is omitted, the coefficient for the proportion of the children receiving subsidies in the county is statistically significant and positive in both periods. Subsidy programs were in large part designed to aid families who had been on AFDC and those who were engaged in training programs while on AFDC. Hence, a strong relationship between the levels of AFDC and child care subsidies in the county exists, and correlations of 0.75 and 0.67 are observed in the two periods between these two variables. As expected, a comparison of Models 2 and 3 indicates that inclusion of both variables inflates standard errors. In Table 4,where both measures are included, the AFDC measure is statistically significant. It is not surprising that the coefficient of AFDC is more robust than the subsidy measure. The measure of subsidy receipt suffers from several sources of error. It omits subsidized clients who received direct payment from the state. Approximately five percent of funds were paid directly to clients in 1991, while 20 percent were paid this way in 1993. In effect, the AFDC variable may better capture the subsidy level than the variable intended to measure 172 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS subsidies. The difference in the subsidy accuracy between the two periods may account for the smaller coefficient obtained in the equation predicting fees in the second period (model 3). Results in the lagged equations (Table 6) are generally consistent with those reported above. As it essentially predicts changes over a two-year period, the coefficient on the proportion receiving subsidy in the county is generally smaller. What do these estimates suggest about the impact of subsidies on child care fees across counties? Consider the coefficients on the county subsidy measure reported in Table 5 . As the difference between the estimates for each period is not statistically significant, assume the mean value, 0.63, applies to both periods. The mean value of the proportion receiving subsidy across the sample of providers is 0.06 in the first period, implying that fees are approximately 3.8 percent higher in that period than they would be in the absence of any subsidy. The mean proportion receiving subsidy across the sample of providers in the second period is 0.09, implying fees are approximately 5.7 percent higher because of the subsidy. Taken together, the implication is that between the two periods, fees grew by 1.9 percent as a result of increases in subsidies. The lag adjustment formulation (Table 6) allows for the possibility that fees may not respond immediately to available subsidies. Consider the third specification, which controls for provider and county characteristics but omits AFDC. The coefficient for the proportion of the county receiving some subsidy across the sample of providers for 1993 implies that fees grew by 1.4 percent over that period due to subsidies to consumers (0.158 x 0.09). Two-thirds of the growth was 'due to a lagged effect of subsidies already in place in 1991, while a third was due to increased subsidies. The lag fee coefficient is 0.664, implying that only about a third of the adjustment occurs over the two-year period. Hence, in the long run, if subsidy levels remained at the current level, fees would be expected to be 4.2 percent higher than in the absence of subsidies (0.09 x 0.158/(1- 0.664)). To summarize, the coefficients reported in Tables 5 and 6 suggest that subsidies observed in 1993 have shifted the demand for child services in each county so that average fees for all child-care consumers are, or will be, four to six percent higher than they would be in the absence of the subsidies. How do estimates of the impact of the subsidy at the county level compare with those predicted by theory? The average subsidy in 1993 for children in the relevant market SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32, NUMBER 1 173 probably amounts to about seven percent of total fees paid.I4 Blau (1993) estimated elasticity of supply of labor to child care in the range from 1.2 to 1.9, which may be used as an approximate elasticity of supply for child care services. Studies suggest an elasticity of demand for child care in the range from -0.2 to -0.7 (Blau and Robins 1988; Hotz and Kilburn 1991; Ribar 1993), although a few are much larger. These ranges imply a total impact between 0.6 percent and 2.6 percent. l5 If the elasticity of demand were as great as - 1.9 (Ribar 1992), and the elasticity of supply were 1.2, the total predicted impact would be 4.4 percent. Hence, the conclusion that subsidies increased fees by four to six percent implies a somewhat larger effect than recent estimated elasticities of supply and demand suggest but are not outside the possible range. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION Fees paid by subsidized clients were about 12 percent below fees paid by others in 1991, but the gap had declined to three percent by 1993. The increase occurred largely as a result of subsidized clients choosing more expensive providers in the second period. Observed correlations between child-care cost and quality indicate an increase in the level of quality for day care as a result of the subsidy program. The subsidy may have succeeded in increasing the quality of care purchased by subsidized clients, one of the goals of government subsidy for child care. With diminishing governmental budgets, if child-care-subsidy programs are to continue to be effective in providing quality care to lowincome children, state policies must develop linkages to other service providers (e.g., schools and Head Start) to meet the needs of the low141n the second period, the average subsidy paid per child is a little over $1,000. The mean value for the proportion of the county day-care consumers that receives a subsidy payment suggests that in the average county, nine percent of children in need of care receive a subsidy. However, this probably underestimates the impact of the subsidy. The subsidy measure includes only payments made directly t o providers which are either registered or licensed by the state. As a survey of clients suggests that half use less formal child care arrangements, the impact of subsidies on the more formal portion of the market may be as high as 18 percent. This would imply an average annual subsidy of $180 per child. Because the average fee is approximately $10 per day, or $2,500 per year, the average subsidy for all children in the relevant market, as a percentage of the fee, would then be 7.2. 'This estimate is based on a simple supply and demand analysis which implies that dlnP/d(S/P) = - E/(N - E), where P i s the fee, S/P is the subsidy as a proportion of the price, E is the elasticity of demand, and N is the elasticity of supply. 174 THE JOURNAL OF CONSUMER AFFAIRS income. States need to be mindful of quality differentials and set payment rates to encourage quality. By providing greater rates to accredited programs and rates sufficient to provide competitive wages to reflect the skills and qualifications of child care professionals, state programs will encourage quality. Our county level analyses suggest that child care providers in counties with greater subsidy levels charge higher fees, whether or not they serve subsidized clients. The coefficients suggest that between 1.4 and 1.9 percent of the growth in fees between 1991 and 1993 could be attributed to subsidies and would indicate all consumers face higher prices as a result of the subsidy. In the long run, market fees may be four to six percent higher because of the subsidies. The model implies these increases are due to the real cost of producing more child care services, including higher quality child care services. Hence, if the program succeeds in improving the access of poor families to quality child care-as the analysis implies-such costs would be modest if the end result is a move to high quality education for all American children. REFERENCES Arnett, Jeffery (1989), “Caregivers in Day-care Centers: Does Training Matter?,” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 10: 541-552. Blau, David M., ed. (1991), The Economics of Child a r e , New York: Russell Sage. Blau, David M. (1992), “The Child Care Labor Market,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 9-39. Blau, David M. (1993), “The Supply of Child Care Labor,” Journal of Labor Economics, 11(2): 324-347. Blau, David M. and Philip K. Robins (1988), “Child Care Costs and Family Labor Supply,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 70(3): 374-381. Campbell, Frances A. and Craig T. Ramey (1993), “Mid-Adolescent Outcomes for High Risk Students: An Examination of the Continuing Effects of Early Intervention,” in Efficacy of Early Intervention for Poverty Children: Results from Three Longitudinal Studies, New Orleans, LA: Symposium for Society for Research in Child Development. Clarke-Stewart, Alison (1992), “Consequences of Child Care for Children’s Development,” in Child Cure in the 1990s: Trends and Consequences, Alan Booth (ed.), Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Cost, Quality & Child Outcomes Study Team (1995), Cost, Quality, and Child Outcomes in Child Care Centers, Executive Summary, second ed., Denver: Economics Department, University of Colorado. Culkin, Mary, John R. Morris and Suzanne W. Helburn (1991), “Quality and the True Cost of Child Care,” Journal of Social Issues, 47(2): 71-86. Feine, Richard (1 992), “Measuring Child Care Quality,” Paper presented at the International Conference on Child Day Care Health: Science, Prevention and Practice, Atlanta, GA. Hofferth, S. L., and D. A. Wissoker (1992), “Price, Quality and Income in Child Care Choice,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 70-1 1 1 . Hotz, V. Joseph, and David M. Blau (1992). “Introduction to JHR’s Special Issue on Child Care,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 1-8. SUMMER 1998 VOLUME 32. NUMBER 1 175 Hotz, V. Joseph, and M. Rebecca Kilburn (1991), “The Demand for Child Care and Child Care Costs: Should We Ignore Families with Non-Working Mothers?” University of Chicago Harris School Working Paper: 92-1. Kimmel, Jean (1992), “Child Care and the Employment Behavior of Single and Married Mothers,” Staff Working Paper, Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute: 92-14. Klein, Tanna, Kathy R. Thornburg, and Judy Mumford (1993), “Child Care, Availability, Affordability and Quality,” Step by Step, 4(3), Missouri Youth Initiative, University Extension, Columbia, MO. Kontos, Susan J. (1991), “Child Care Quality, Family Background, and Children’s Development,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 6: 249-262. Leibowitz, Arleen, Jacob Alex Klerman, and Linda J. Waite (1992), “Employment of New Mothers and Child Care Choice: Differences by Children’s Age,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 112-133. Michalopoulos, Charles, Philip K. Robins, and Irwin Garfinkel (1992), “A Structural Model of Labor Supply and Child Care Demand,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 166-203. Mueser, Peter R. and Robert 0. Weagley (1993), “The Impact of Government Subsidies on Child Care Rates in the State of Missouri,” Report prepared for the Missouri Department of Social Services, Columbia: University of Missouri. Nelson, Margaret (1990), Negotiated Care: The Experience of Family Day Care Providers, Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. Office of Socio-Economic Data Analysis (1992), A Social and Economic Atlas of the State of Missouri, 1980-90: Data Appendix, Columbia: University of Missouri. Phillips, D. A. and C. Howes (1987), “Indicators of Quality in Child Care: Review of Research,” Predictors of Quality Child Care, D. A. Phillips (ed.), Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. Ribar, David C. (1992), “Child Care and the Labor Supply of Married Women: Reduced Form Evidence,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 134-165. Ribar, David C. (1993), “A Structural Model of Child Care and the Labor Supply of Married Women,” Working Paper, University Park: Pennsylvania State University. Walker, James R. (1991), “Public Policy and the Supply of Child Care Services,” in The Economins of Child Care, David Blau (ed.), New York: Russell Sage, pp. 51-81. Walker, James R. 1992. “New Evidence on the Supply of Child Care,” Journal of Human Resources, 27(1): 40-69. Whitebook, M., C. Howes, and D. Phillips (1989), Who Cares? Child Care Teachers and the Quality of Care in America: Final Report, National Child Care Staffing Study, Oakland, CA: Child Care Employee Project.