Distributional Effects of Early Childhood Programs and

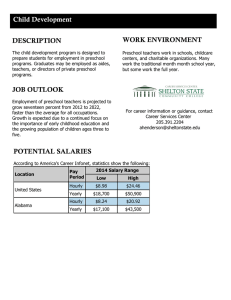

advertisement