Black‐White Achievement Gap and Family Wealth National Poverty Center Working Paper Series W. Jean Yeung, New York University

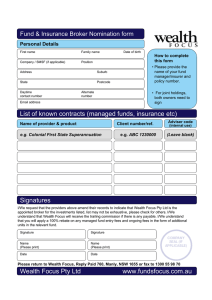

advertisement