Poverty, Migration and Health

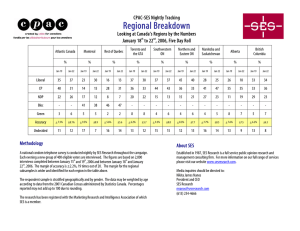

advertisement