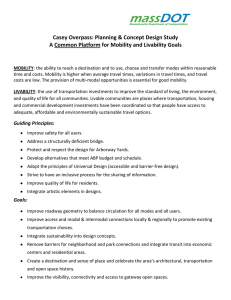

Enhancing Mobility to Improve Quality of Life for Delawareans July 2010

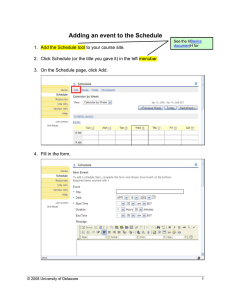

advertisement