P - ;-i I -- : ~ .~

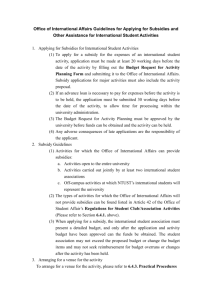

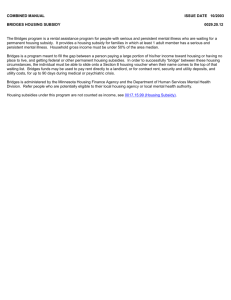

advertisement