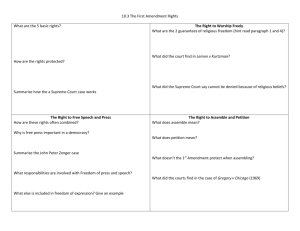

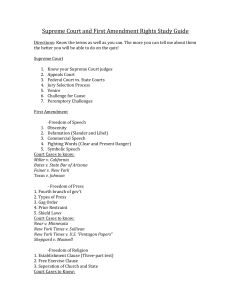

Freedom of Speech and Press: Exceptions to the First Amendment Legislative Attorney

advertisement