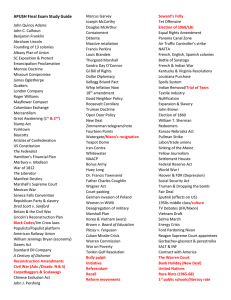

���������� �����������������������������������������������������������������������

advertisement