August 2008 Institute for Public Administration www.ipa.udel.edu

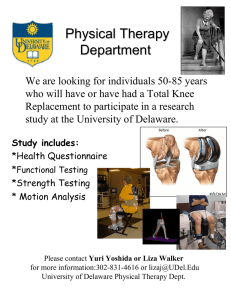

advertisement