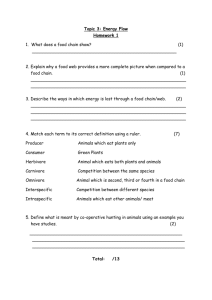

etAPOWERINO Prepared David Gasquoine. For: PRIMARY INDUSTRY

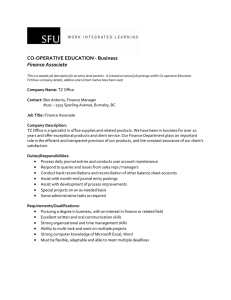

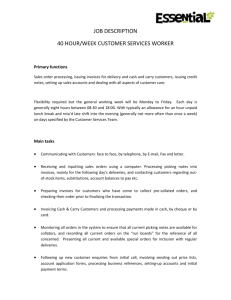

advertisement