Document 13936593

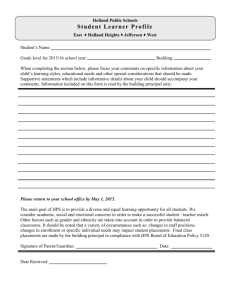

advertisement