Review of non-academic literature and resources relating to Community Severance

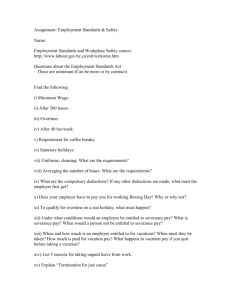

advertisement