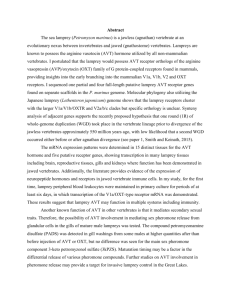

AN ABSTRACT OF THE

advertisement