AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF

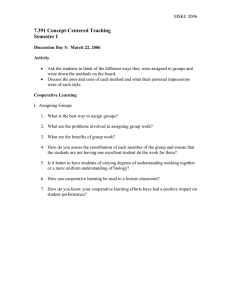

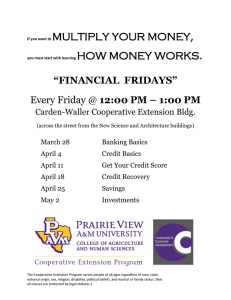

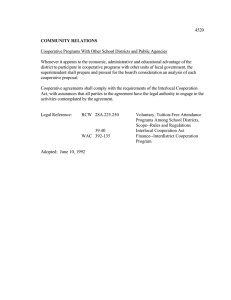

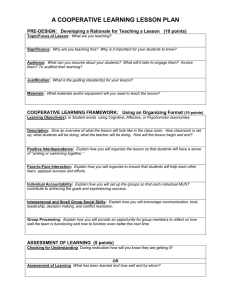

advertisement