Document 13887902

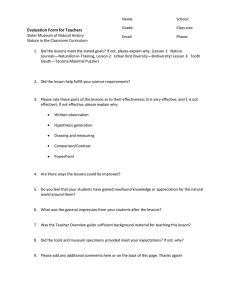

advertisement