Government Contracts and

Procurement Policy Alert

December 2007

Authors:

David Crandall

412.355.6269 david.crandall@klgates.com

Mark Rush

412.355.8333 mark.rush@klgates.com

Robert Sherry

214.939.4945 robert.sherry@klgates.com

K&L Gates comprises approximately 1,400

lawyers in 22 offices located in North

America, Europe and Asia, and represents

capital markets participants, entrepreneurs,

growth and middle market companies,

leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100

global corporations and public sector

entities. For more information, please visit

www.klgates.com.

www.klgates.com

False Claims Act Correction Act of 2007

A bill recently introduced in the Senate would dramatically expand the number of actions

filed under the False Claims Act (FCA). Although the bill – the False Claims Act Correction

Act of 2007 – purports to “modernize and strengthen” the ability of the Government to fight

fraud, the bill would instead encourage meritless whistleblower suits and remove important

procedural safeguards imposed by the courts. The most significant change would allow

plaintiffs to bring FCA claims without exposing any fraud, undoing the Supreme Court’s

recent decision in Rockwell International Corp. v. United States, 127 S. Ct. 1397 (2007).

The bill would also increase the scope of the FCA and broaden the power of the Attorney

General to conduct investigations. While the sponsors of the bill claim that the changes

will reduce fraud against the Government, the bill offers little hope of exposing more

wrongdoing. Instead, the bill, like certain related provisions in the recently enacted Deficit

Reduction Act of 2006, will facilitate qui tam nuisance suits. The bill, if enacted, would be

particularly troubling to health care, technology, and defense companies, which are already

subject to frequent nuisance suits under the FCA.

Background

The FCA rewards whistleblowers for exposing fraud against the Government. In return

for divulging the wrongdoing of their employers, whistleblowers receive a portion of

the recovery, usually between 15 and 30 percent. The awards can be substantial; recent

recoveries have exceeded a billion dollars. The FCA further sweetens the pot by awarding

costs, expenses, and attorneys’ fees to prevailing plaintiffs.

Central to the FCA is its qui tam provision allowing private plaintiffs to bring claims in the

name of the Government. After the whistleblower exposes the alleged fraud by bringing a

qui tam action, the Government investigates the allegations. If the allegations are credible

and sufficiently serious, the Government intervenes and assumes control of the litigation.

Otherwise, the whistleblower proceeds alone. Although the Government investigates every

action brought under the FCA, it ultimately intervenes in only about a fifth of cases.

The qui tam provision has proven successful in uncovering fraud, resulting in the recovery

of over $12 billion for the Government. Most of the recoveries, however, have come from

the 20 percent of cases in which the Government has intervened. Indeed, in 2006, the 80

percent of cases in which the Government refused to intervene led to the collection of only

$16.6 million of the approximately $1.4 billion recovered.

Defendants face immense pressure to settle the qui tam suits. For most defendants, the

cost of litigation alone exceeds the price of settlement. Some defendants also face possible

exclusion from federal programs. The health care industry in particular is vulnerable because

of the risk of exclusion from Medicare and Medicaid. The plaintiffs’ bar has taken advantage

of the situation, resulting in many nuisance suits being brought under the FCA.

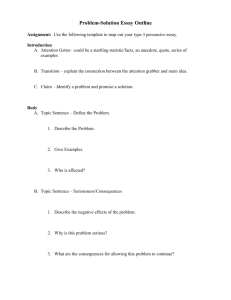

Government Contracts and Procurement Policy Alert

The Bill

The False Claims Act Correction Act of 2007, if

enacted, would aggravate the misuse of qui tam actions.

The most important provisions of the bill are:

Weakening the Public Disclosure Bar. Perhaps

the most significant provision of the bill is the near

elimination of the “public disclosure bar,” an important

defense against qui tam actions brought under the

FCA. As the Supreme Court explained in Rockwell,

a plaintiff may not proceed with litigation based on

publicly available information unless the plaintiff was

the “original source” of that information. To be the

original source, the plaintiff must have “direct and

independent knowledge” of the allegations underlying

the qui tam claim. The public disclosure bar thus limits

rewards to those individuals actually exposing fraud.

The bill would limit the public disclosure bar in several

ways. First, the bill would define “public information”

narrowly. Only information “on the public record” or

“broadly disseminated to the general public” would

bar a claim. Information gathered from Government

employees or Freedom of Information Act requests

would not be considered public. Consequently, even

if the Government already knows about the alleged

fraud, or the information is available to any member

of the public upon request, the information would

not be “public.” Second, “all essential elements”

of the plaintiff’s claim would have to be publicly

available. Plaintiffs would be able to escape dismissal

by showing one non-public source of information,

such as a Freedom of Information Act request, rather

than the current standard of “direct and independent”

knowledge of the fraud. Third, only the Attorney

General would be able to invoke the public disclosure

bar. The defendant would have to convince the

Attorney General, rather than the court, to dismiss the

plaintiff’s claim. Whether the public disclosure bar

applies would be within the discretion of the Attorney

General.

The sponsors of the bill claim that the public disclosure

bar discourages whistleblowers, but it is unclear how

weakening the bar would expose more fraud. Rockwell

itself provides an example. In that case, the plaintiff

filed a qui tam action under the mistaken belief that his

former employer engaged in fraud. The Government,

in investigating the claim, found that the employer

engaged in an unrelated fraud after the plaintiff left

the employer. The Supreme Court denied recovery to

the plaintiff because he did not expose the fraud to the

Government; rather, the Government investigation did.

The sponsors of the bill have made clear, however, that

the plaintiff would have recovered had the revisions

been in effect, despite the absence of any discernable

benefit to the Government.

Permitting the Attorney General to Delegate

Investigations to Private Parties. Another important

provision of the bill would allow the Attorney General

to delegate the authority to issue civil investigative

demands (CIDs). Under the FCA, the Attorney

General may demand documents, answers to written

interrogatories, and oral testimony, even before a

lawsuit is filed. The FCA currently tempers this broad

power by limiting it to the Attorney General. Under

the revisions, however, the Attorney General would

be able to delegate the power to third parties. One of

the few checks on unlimited fishing expeditions – the

limited resources of the Attorney General – would thus

be removed. The bill would also allow any information

uncovered to be shared with qui tam plaintiffs, although

the third-party delegates and qui tam plaintiffs would

often be one and the same.

Abandoning the Presentment Requirement. The bill

would eliminate the “presentment requirement,” a

rule limiting FCA liability to those companies dealing

with the Government directly. Instead, liability

would extend to all companies directly or indirectly

seeking Government money or property. The bill

would overrule the D.C. Circuit’s decision in U.S.

ex rel. Totten v. Bombardier, 380 F.3d 488 (2004),

which refused to apply the FCA to claims presented

to Amtrak.

Redefining Government Property to Include ThirdParty Funds. The bill would expand the definition of

“Government property or money” to include third-party

money and property administered by the Government.

This change would specifically overrule U.S. ex rel.

DRC, Inc. v. Custer Battles, 444 F. Supp. 2d 678 (E.D.

Va. 2006), which refused to apply the FCA to Iraqi

funds administered by the United States.

Lengthening the Statute of Limitations. The bill would

lengthen the statute of limitations to ten years after the

fraud. Plaintiffs must currently bring actions within

six years of the fraud or within three years of the

Government learning of the fraud, whichever is later,

December 2007 | 2

Government Contracts and Procurement Policy Alert

but in any event no later than ten years after the fraud.

The bill would also allow the Government to come

within the limitations period by relating back to the

original filing date of a qui tam plaintiff.

Allowing Government Employees to Bring Qui Tam

Actions. One of the most controversial provisions

of the bill would allow Government employees to

bring qui tam actions. Although the bill would require

the employees to report the fraud to a supervisor and

the Attorney General and then wait twelve months

before filing an action, the proposed change raises

questions about how much Government employees

should personally profit from their work. The change

also creates the potential for strategic behavior by

Government employees.

Adding Offenses Giving Rise to FCA Liability. The

bill would expand FCA liability to additional offenses

not currently covered by the Act. Companies keeping

overpayments would be subject to liability, as would

companies converting funds to unauthorized uses.

Implications of the Bill

Expanding FCA Liability and the Number of

Nuisance Suits. Most of the changes proposed by

the bill would expand the reach of the FCA without

exposing additional fraud. The weakening of the

public disclosure bar, for example, would only reward

plaintiffs for filing mistaken claims or claims based on

information already known to the Government. No

new fraud would be exposed.

Even the proposed changes that may expose more

fraud, however, would expand the range of activities

subject to nuisance suits. The plaintiffs’ bar would

have a new range of targets, including companies only

indirectly receiving Government funds and companies

doing business with third-party funds administered by

the Government. While the goal of limiting fraud is

enviable, that goal comes at a high cost.

Removing the Protections of the Adversarial Process.

One of the most threatening consequences of the

bill would be the removal of procedural safeguards

meant to protect defendants from meritless suits.

Investigations previously restrained by the courts

and the limited resources of the Attorney General’s

Office would instead be in the hands of the plaintiffs’

bar. Companies would face costly fishing expeditions

without the benefit of court oversight. Further, one

of the most effective weapons against nuisance suits

– the public disclosure bar – would be removed from

the adversarial process and left to the discretion of the

Attorney General.

Conclusion

The False Claims Act Correction Act of 2007 would

dramatically expand the number of qui tam lawsuits,

without offering much hope of exposing more fraud.

Moreover, the bill removes important procedural

safeguards against meritless claims. Companies,

particularly in the health care, technology, and defense

industries, should be aware of the potential impact of

the bill. K&L Gates attorneys will be following its

development closely.

K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP qualified

in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, and in Beijing (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP Beijing Representative

Office); a limited liability partnership (also named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London

office; a Taiwan general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general

partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations

in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office.

This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied

upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer.

Data Protection Act 1998—We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP seminars and with our

regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klgates.com if you would

prefer not to receive this information.

©1996-2007 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP. All Rights Reserved.

December 2007 | 3