UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 19

advertisement

UCL

Working Papers in

Linguistics

19

2007

Department of Phonetics and Linguistics

University College London

Gower Street

London WC1E 6BT

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk

Contents

Page

Editorial note

v

Linguistic Theory

Twangling Instruments: Is parametric variation definitional of human

language?

NEIL SMITH & ANN LAW

1

Phonology

ATR allophones or undershoot in Kera?

MARY PEARCE

Consonant clusters in the acquisition of Greek: the beginning of the

word

EIRINI SANOUDAKI

31

45

Syntax

Verb movement and VSO-VOS alternations

DIRK BURY

On the prosody and syntax of DPs: Evidence from Italian noun adjective

sequences

NICOLE DEHE & VIERI SAMEK-LODOVICI

Eliding the Noun in Close Apposition, or Greek polydefinites

Revisited

MARIKA LEKAKOU & KRISZTA SZENDROI

Relatives and Pronouns in the English Cleft Construction

MATTHEW REEVE

Japanese wa-phrases that aren’t topics

REIKO VERMEULEN

77

93

129

157

183

iv

Semantics and Pragmatics

Generativity, Relevance and the Problem of Polysemy

INGRID LOSSIUS FALKUM

Subsentential utterances, ellipsis, and pragmatic enrichment

ALISON HALL

Plurals, possibilities, and conjunctive disjunction

NATHAN KLINEDINST

Logic in Pragmatics

HIROYUKI UCHIDA

205

235

261

285

Appendices

Contents of UCLWPL vols. 1-16

UCLWPL subscription/exchange

321

333

Editorial note

UCL Working Papers in Linguistics features research reports by staff and graduate

students of the Department of Phonetics and Linguistics, University College London.

Reports on phonetic research in the Department appear in our sister publication,

Speech, Hearing and Language.

This is the first volume of UCL Working Papers in Linguistics that is published on-line

only. The Internet edition of UCLWPL includes an archive of viewable abstracts and

downloadable copies of all the papers in this volume.

Richard Breheny and Nikolaos Velegrakis

London, November 2007

http://www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/PUB/WPL/uclwpl.html

Linguistic Theory

! !

! "

!

&' "

"

+

!

+

"

$

6

?

!

$

#

!

$ %

$ ()

! !

$

*+

,

!

$

$ + ! $

./01

*

!

+ " ! / 2 + " !

!

*+

$

* $

+ ! $

*

+

! $

!

3+ $ *! $

*

$

! $

+ $ *"

$

"

$!

/0

,

!

/0

,

!

"

4

/0 $ !!

!

"

"

$

/0 $ !!

*

5

$

"

%

$

.

!1

/0

$ $

. 1 "

-

! 7

"

!

$

$7 .:;<=1

4!

2#

@ $7

.(AA>1

$ $"

$

$

$

2 ./ !

B *$7 (AAC1 B $

+ !

.(AA(1 + +

!+ $ *+

D

+ +

F

+ $

$

+

$

9$ /

G *

" 7

* $

, 89

+

'

$

B

*

.:;>:1

*# "

?+

*

$

,

E $

+ (AAC

7 +

! 8F 9 $ !!

$

*

! ' ! 7*

" ' ! $7 $ !

H

!

!

I

*

+ $

! 7

"

$!

$

?.+ " " *1 $

2:

.+ " " *1

$

,

"

$ $

$

. 9

2 :;C<

# $

9$

(AA< !

(AAJ1

! *

"

,

!

$ $

$

$ *

.G

(AA<1

!+

./ *

(AAA:K<1

+

+

+ +

!

+

+ ! $

./01

*

!

$+ " !

+ HH

$,

./

2

+ " ! ' ! 7* :;=>1

!

*+

$

I +

2

.(AA>1 +

+ !

$ !

/0 $ $

$ !

4 !

! 2 .(AAC1 +

! $

7

+

"

/0

,

!

$

!

!

$

?+ ! $2

-$

+

"

+

,

/0

!

! *

"

!

$ $

$ $

!!

* $ -$

,

!

! *

$

!"

+ +

$

+ +

$

(

+ +

/0

$ $

$ "

+ ! $

3+ ! $

#

$

K

+ +

!

! $

+ $

!

*

! $#

$

J

*

!

! $

+ $

"

9

*

$

<

!"

$ $

.:1

.:1

9

/0

" /0

$ /0

$

/0

,

!

,

,

$ !!

!

!

$ +

:

*

+

"

$

/

+ " !

*

%

.1

!

+ $

$ $ ! + $

*

"

/0

"

$

"

$

!1

"

.: 1

/0

" $

5

.

$

*

"

*

-$

/0 $

4

!

$ !!

$

$

"

!

/0

2 + " !

$ !+ - *

(AAC +

2 .(AA(1 $ !

!

*

!

+ $

? $

2

+ " ! $

*

$

!

/0

+

?/

$

$+

/0

"*

!

$

+

$

$+

/ !

2

* .' ! 7* :;=: #

*

! :;=C# B "

:;;C# 7 (AAK1

!

$ *

*

$"

!

$

"

9$ *

?"

2

.9 1

+ +

"+

$ *

9$ *

?

2

.9 1 .

(AA(1

!

$

*

+

! $ ! $

!

+

+

$

$

$*

!! $ " *

* +

9

!

! " !" "

"

" " 9 5

$ ! *

" !+ * 3 "* *+

,

!

,

9

$ $

!

E

G !! .EG1

!

$

$

$

" $ !

!

+ $

!

$

-$

$ !+

!

?' !+

* !2 .

' 5

1

-$ $

-$

$

$

+

+

$ ! + 3 * $$

!

$

7

$

$*$ +

$

!

7

+ $

"

* " .+

$

!

1 $

!

.! +

$

!

1 "

.$ 1

. * $$

!

1

$

. !

$

!

1

7

$*$ +

$! ! *

*

$

* $ $

!

" !" "

" HH

* $

*

-$ $

$

$

7 +

+

!

EG

+

-$ +

+ $+

$

$

+

$

.' ! 7* :;C:1 . $1 $*$ $ * .9

:;;;# ' ! 7* (AA(1

/ 4$

/ $+ .' ! 7* :;;<1 $

$ $

+

$ !+

$

+

$

+ $+

$

!! $

+

5+

$ ! +

$

* $ $5

"

$

!+

, $

!

+

" * $

!"

$

-$

9

$

!

,

! $

$

!

.(1 $

* $ $$

$

? - *

"2

! !

+ $ +

.

1 "

?

2

.(1

$!

++

"

! "

!

$ !+ -.K1

+

" ,

.J1

*

+ $

$

.(1

!

.K1

!

!5

!

!8

!

.J1

!

!

" D

!8

!8

$

+

$+

$

$

? *+

.J"1

+

"

$

"4$

.<1

*

! 7 ! 7 7

+ 4$

+ $+ . //1

.< 1

$$ + " " .<"1 !+

$,

+ $2 $

$

!

@ $!

!

*

" D' !

!

*

+

! ?+ 3

-$ +

$+

!

+2

* ++

!

+

"

$

+

$

$ -$ +

.

$ !+ ! 1

!+ * +

+

$

$

+

?

$ 2 5

$ + !

$

0 "

3 "4$ . ?+ 3

!

"4$ 1

!+ *

!

1

! $$ $

+

+ !

*+ $ * $ $ +

+ $

$+ +

* 3

$

+ !

/ +

+ $

+21 + !

.

$

$

3

!

+ !

.

++

.>1 .=1

.>1

5L

3

$ 4

*

$+

*

!

!

!

!"

*+ $

- !+

3

.C1

3+ 3

.=1

3

*+ $

+ 5 DL

7

I 5 DL" *

- !+

9

"

" M5

+

$

@+

EG

M5/ 3

$! M 5

*

"

+ 5 LN 7 ! 7

7

I 5 LN

+

+

L! H+ M

"

*

7

*

" * $!

"*

$ !+ - $

?O

*3

M

M

$ $

$

2

$

9

$

$

* "

?O

! *

.;1

*3

2

!

"

.;1

!

"

! * "

!+

"

$

@+

+

.:A1

" # PP $ %&"

!

$

$

*

++

@+

"* +

!"

9 $

$

$

.:A1

'

*

!

$$

*+

*

+ !

*

$,

0

!

2

.!

3

' ! 7* :;=>1

!

$

$

$

" + $

"4$

$

$,

$ 2

7

$

$

+ !

"

!

-+

5

$

!"

G

7 *

! $$

$,

L

+

"

&! ) "

*

"*

M. !

(AAJ =K1 * *+

+ $+

* !

$

$

!

' ! 7* .(AA> :=K1 +

L $,

!

+ !

$

* !

%

+ $+

EGM

*

$ ?

2.

*

! P

"

1

+

7

$

*

$ $

!!

!+ $

+

+ ! $$ $

7

$

$

* $ !

$,

* + $

?

$ 2

$

$ $,

7 *

7 + $

$ $ +

+

$ !

/0

,

!

$

"

*

5 /0

+

++

EG

5 "* *+

5

!

!

!

EG

.(AA>1

7

.(AAC1

"

+ +

(

?E

G !! Q 7

EG

-+ $

$

/0

!

!

!

*

"

2 .(AA> =(1 "

$

! $ +

*

+ *

$ !+ "

+ ! 3

$$

*$

!+

! 7

$ !

3

"* - $

!

! +

*

$

/0

*

$

+

"

(

9

"

+

" !

$

.(AA> J:;3J(A1

!

!!

*

!M

LE

*

"

$ $

$

3$

(

"*

!

!"

$ !!

*

"

"

!

"

+

!

*$

"

$

#

!

$ !

* -

!

!

7

$

,

7 /0

/0

#

+ *"

! +

!

+

$ !+ - *

/0

$

"

$

"

+

*

!

*

$,

!

+

7

/0

*

!

EG "

(AAJ

*

-

6

*

+

$

$+

2 .:;=J1

$

-$ .

!

$

1

R*

+

L * $ $+ !

% $

*

+ +

!

-$ M .R *

(AA< J1

' ! 7*

! *

.

' ! 7* :;;<1

+

-$

$

$

-$

"

$

$

$

$

' !+ !

I !

$

$

$ $+

-$

$

"

$

$

0 "

4$

.+

+1/ +

)

"

"

$ $+

-$

! $

"

$

-$

! 4

$

$

$

! !"

$

-$ $ $

$ *

$*$ +

$ 7 . -$ +

+

1

!

!+

* ! *

$7 * +

$

$

"

!

. 7

B

1

!+ *

!

. 7 +

G 71

!+ * .

1 "4$

. 7

G ! 1

+

"

$

$

!

/0

$

$ 3

$

$

"$

+ +

" $

#

*

# "

%

!! $ .

! 1

!! $ .

1

!

.

3

+ ! $1

$ $+

-$

? 2 * !

+ 3 ++ !

+

"

//#

?

2 * !

+ 3 ++ !

$

.

$

$

*1 GB S /B6 . + 3 +

1#

GB T /B6 .

3+ 3 +

1 B$ *

!

? GB2

! !

!

+ !

!

" L& + $ /) "

*M

$ + 3 +

+ + * + $

$

$

$

$

.

1

$

"

$

"

$

"

!

"

*

"

.

$

*7

+

1

$$

$

$

$ $

+

+

"*

+

B"

"

!

"

$

+

$ !!

9

/9 9 +

$

$ $+

3

* !5

$ * $

$

+

/9

+

$

3!

* !

$ *

$

$

* !

$

9

$ +

"

3 !

$

!

! "

+ "

"

$

-$

!

U+

U

$

*

!

+

/9

9 + $ * B B

$

$

L

$

* $$$

$

"

* U+M

-$ $

$

0 "

* U+ U

-$ $

! "

+

"

"

$ "

$

$

$

'. !+ !

1 .

1 I. !

1! *"

$

*

?$

2

!+ *

*

+

/9

*

* $$ *

K

!

$ *+

"

+

$

+

"

+

"

"* EG

$

$

I

! 7

!

"

+ $

3+ $

!

* $

*

$

$

*

"

* - "*

.B B

(AAK KA1

! 7

$

$ $

*

!+ - !+

$ !

* P ,

! 7 * $ $ * "*

+

$

" $ ! + ! O

$ ,

9 $ O

! 7

,

$

4 "*

.*

#

,1

O ! 7

,

+ $

!

+

.

"" *

%,1

O ! 7

$

- *!

.- "*

%,1

*

$ /0

$ $ "

&UP3

)

$

$

9

$

+ !

$

*"

* "

$

$

+

$ $+

$ !

*

$ "

$ !+

/0

$

$

, $

$ $

+ $

! + !

$

,

* "

$

"

?! $ 3+ ! $2

?! $ 3+ ! $2

? $ 23/0 *+ $ * - !+

"*

3

$

.

P

1 + !

.' ! 7* :;=: 1

7 2 .:;;>1

+ **

+ !

$

!

! +

$

$

$

+ !

*

$

?! $ 3/02 5

- !+

"*

$ $

- *

$$ !+ *

$$

" ./ !

:;C=#

H :;=>1

$

!

"

$

.

H

(AAC1 $ $

$ *!

$

$

+

*

+ $

B"

.:;;C (CK1

!"

K

B

.B B1 .(AAK (=1

*! *

+

$

$

!

(AA< $ :<

$

.

$ +

P! $ 3

9

!

!

! $ 3

$

+ +

$

$ $

!+

/0

3+ ! $

$

!

$

*

* +

+ !

$

* + $+

$ "

! $ 3 !$ 3

3+ ! $

9

$ R*

$+ $

$

"

!$ 3

! $ 3+ ! $

L&) * + !

! $ + ! M .R * (AA< :A1

+ " " * L&) *

$

! !

" "* EG

$

! * $ $ + ! M .+ ::1 5 +

+

!

.++ :J3:<1

"

:AA

$

!

9

L "*

!

$

!

!

M .+ :>1

+ " !

$

$

!

" L !+

!

*+ M . " 1 $ " R *

!

L$ $ H

$ 3

$ * $$

$ M . " + >1

- !+

$ $+

$

"

9 $ +

/

!

*

H

.(AAC B

H 5 +$1

* *

$

"

"

! $ 3

!$ 3

+ ! $

"

+ ! $

3+ ! $

+ $

+

R*

$

$

-$ "* +

!"

" $.

1$

.$

B"

B

(AAK (J1

H

"*

+

!+ * ? -$ 2

+ $

*

$

!

$

$ $ *

3+ ! $

$

+

"

"

* $$

$

!

!

$+

?+ ! $2#

$

$

$

$

"

! $

!$

"

+

*

7

+ $+

$ !

*+

/0 5 ! $ 3/0

$ L $ H

+ $ $

M

! $ 3/0

+ L *+

*$

M "

' ! 7*2

L

!

"

! 4

$

"

! $ + !

7

+ !

%

! $ ?! $ + !

2F

L "

" ! $

* "

!$ 3

M

*

L" $ *

$$

M5L

+

$

7

$ M .+$I $ !" A>1

++*

!

3$ !!

?! $ 3P

! $ 32 !

"

!+

+ ! $

3+ ! $

!+

*$

/0

!

$ !+

$

/0

" $

*

-

$ $ *

+

* B

$

$

$

"

- !+

0

+

"

* "

/0

$

$ .$ I

"

+

!

R * :;;A I

-$

$

$

:;;;1

" +

*!

"

$

$

$ $

*

$$

*

$ $+

$ $ + + * /0

$,

$

?

2

+ *$

$

.

+ $

*+

$

1 + *

$,

' ! 7* .:;=A:KJ1 +

L $

!

*

#

!!

!

$,

$ * +

+

$

$

+!

7

?$

" !

?

2 "

" $

$

"

!

$+ +

$

!

+ $

M

+

2

7 *

"

$+

+ $+ 5

! $

+

" !

*

+

" 3

2 3

*

L

!

*+

!+

-+

$

$

!* "

$,

* + +

$

$,

"

$

J

7

$

!!

$

!"

$ !

?

!+ $

$

! ?

"

$ *

* ! +

2

$

J

$

7

-+ !

:;;;1

1

"

/0

"*

7 @

!

+

.:;<C ;>1

$"

+

*$

*M

$ *

.' ! 7* :;=>1

! 7

"

*+

*

/0

5

!+ $ $ ! 3

!

$,

.$

9

:;;K - 1 "

$,

$ $+

+

*

*+

$

! "

$ $

$ !

+ ! $$ $

!

+

*

+

!

*+

$ $ ! "

!

$$

*

+

$

+ $

$

60 / /

$$

!

+ !

$

+

"

$

*

$ 2

7

!

"

+ $

+ +

+

.$ /

3/ !

:;=;1

7

2

?7

-+

$2

+ ! $$ $ ! *

+ " ! $" $

"

. ! 1

$

$ "

$ !

.

:;;;

"

!

+ +

7

$

.

12

$ $

$

7

"4$ 1

$.

0 " + $

"4$ 1

$ .

/ +

+ $

-+

?' $ 2

" $!

" " $

$

+ +

$

.

" *1

+ 3 +

+ !

.

$

$7 !

(AA>1

$

! *

"

* $ $

$

" +

!

$,

$

$

$

+

?$ $ $ $

2.

$

+ !

"

$"

+ ! 1

$

$

*

"*

/ 2 + " ! . + 1 .

<

$

!

' ! $7 (AA(1

$

!+ $

?

$ 2

+ ! $$ $

$

!

.L

*

7

*

3+ ! $ $ $ M !

(AAJ :(:1

$

*

"

$ *+

" ! 7

$

! 7 9

+

*

"* * ! .:;=C :=1

$ $+

! 7

"

$

7

?

72

$ " "* B "

.:;;C (C<1

+ !

+

$

$ !+ - $

* !

$

$

$ $

!

$

$

"

+ ! $

3+ ! $

#

$ $!

"*

7

$

* /0 +

$ $

?

$

*7

2

" $+ + *

$

$

!"

$

/0

!

3+ ! $

+

*

$

/0 6

$ $

$

"* + ! $$ $

!

" $

* +

'

$$ !

+ $ $ *

$ $ +

$

-+

$

!

*

!

-+

$

$

"

$ *

$ $ +

I +

$

+ $

!

*

/0

" $

.!

*1 +

$

$ ' !+ "

! 7 "

2 .:;;C1

$

? $+

2

+

+ ! *

+

! 7*

+ $

* ! $ $+

"

$ $

+

"

7

! +

. !+ 1 + $

!+ * " $

"

!

?$

+ $

2 $

*

$

"

$

"

+

$+

*

$ * $ !+ "

+ $ 9

!

2 ? $+ $

*" 2

+ " "* "

<

$ $

$

- !+

?

* -

$ $

! *" +

2

!

"*

$ $

" ! $

$

$

?

P+ 7 2

U/ 3I +

$

+ 7

11

"

" $

"

$!

6

$

! +

*

1

$

$

$

6

$

*

$

$

"

*

!

$

!

$*

* ! $*

!+

- !+

+

"*

*+ - !+

"*

!+

" *

D

3

.!

7

$

+

!

# 4# 4#5

" /0 " $

"*

* ! $

+

" * $,

7

"* * + $

+

$

+

- !+

+

"*

$

! *

+

$

+!

.$

!

:;CK :>K1

$ $

* $$

+!

.$

!

(AA< (;1 9

$

$

*

!

!

! *+

$

" $ & 7)

& )

+ $ *

"

!

$

! * "

*

$

/0 " $

+ $

$

++

"

+

+

$

!

+

$

+

!

" $

"

$

+

"

$ $

& 7) & )

* $ $

+ $

$

*

.$

! *1

$ $

*+

$

$ $$

?I +

$

+ 2

+

+ ! $

$ $ !

$ +

"

. !"

1

* $$

+

$ - !+

+!

*+ $ *

$

+ +

$

$

$

! * *?

$

2

? $

2

7

"

3

+ ! $

! *"

! EG3 $

$ " "* '

$

.$ '

/

7 (AA(1

$

+

$

!

$

$$

+ .

?6

" %

$

,21 " $

$

$

"* EG

$$

>

7

+ +

I +

+

$ *

7

$

$

! *

+

*

* -! 7

$ $+

$

"

+ ! $

3+ ! $

$

6

$

/0 ! "

!

$

+

$ ! " $

-+ $

+ !

$

"

+

!

, !

3

+ ! $

!

$

!

+

!

' ! $72 .(AA(1 $

?+ ! $+

*2

*

?

!

2

!

+

$

!

>

7

+

-+

* I

! 7

$

!

3

$

!+

* ! 3

1

! + !

? , $

!+ *

"

*

"

2+

!

9 ! * + 7 - "% $

7 %

,

!! $

* - "% $

7 %

M +

" #

+

$

!

' ! $7

+ !

"

!#

+

7

$

?

!

2

3+ ! $ ' !+ "

- !+

$ "

+

*

V + .(AAK =AJ1

- !+

!

+ +

+ 3$

$

*

$

$

!

L

!

P*P& )

!

"*

!

M

$ $

L+ 7

+

$

" $ $ $

$

M

$

3+ ! $

" :

!!

- !+ *

$

$

$ !!

* +

*

!

+

$

"

/ ! $

! #

% & '

$

3+

+

-$ +

/

!

#

$

3+

3

.

(

/

?

!

$

! +

. $%

*#

8

! $

# $

!

$72 & 7) & )1

!

3!

1

$

!

!

$

3+ ! $

I $

+

# 4# 4#1

.$

!

$

3+

*3

*

# (

/ ! $

/ 3 +

' !+ *

!

'

5

!

*

)

(

/

O

-$

$

+

*

*

$

3+ !

, $

/ 3$

$

! *

.

1

$

.D

3#

1

$

$

-$

*

C

$$

++

!

$

/0 +

!

++ +

!

! +

* .

!

-$

$ ++

!

1#

! +

+

*

* "

.

! ! +

$

1

$

" 4 *

$

* $

*

* /0

! +

!

.

$ $

$1! *"

$

$

$ $

/0

+

"

! 7

$

*$

$

?$ $

$237

9

+ 3

=

!

!

$

! *

+ +

+

+

* "

$ $

!

$

*

*+

./ 7 :;=J1

L

*M .' ! 7*

:;=:" ((J1

$

$ !

!!

$

!

!

!"

+

"

$$

$ $ +

$ !+ "

/0 "

$

!

+

+

"

/0 $

+ $

7

$ $

$ !+ "

+ ! $

$,

" *

! $

$,

+

$

!

++

*

$

!

+

+

+

!

$

"

$

! *

/0

$

!

*

" ,

=

+

"

*

1

.

"

!

*$

$ *

$

*

*

"

$ $

!

4 !

$

?

2

*+

$

+

.$

+ 3

+

1

$

+ $

+

4

"*

1!

*

$!

7 "*

*

++ $ " !

+

!"

!

$ .

"

1

C

7

$

*

!

5

5

3 -$ .$

:;=C =C1

!

(AA< .? $7 21 $ $ $

$

! *

"

7"

*

! $

! .:;;;1 "

$

*

! 7"

$

*

!

.

+ ! $

.(AA<1

"

!

"

$+ $

/0

+

$+

" !

! 7

*

+

1

7.9

"4$

,

I $7 + $1

7

"

$

$

$

4

!

- ! $ * !

$

$

*

$

+

*

!

7

+

$

$ + +

"

?

2

-+

$ !+

$ P+

! $

$

$

7

$

;

* $ $

"

$,

+

*

!

3

#

5

$

!

#

+

+

+!

*

.

1 !

.$ / +

:;;=1

' ! 7*2

"

"

!

*

.$ ' ! 7* :;C<1

L !

+

!

! "

* $

!! M .' ! 7* (AAK JA1

.(AA> $

(AAC1

7

.(AAC1

"

*

!

4 !

$

! *

! 7

7

+

+ $+

4 $

?

2

L&) +

*

-+ $

*

+ $+

$ 3$

*

$

+ ! $

#

-+

$

!

$

2 + $ $

-$

M .(AA> C(1

*

*

L&)

!

*

!! +

7

"

+ $ $

!!

$ $

+ $+

+ !

!

!! +

7

"

!+ !

+ $

+ $+

+ !

"

M .(AA> CJ1

!

$

*

!$

$

4

+ ! $$ $

Q

!

$

$ !

E

G !!

7 L

!

*M

EG "

$

+ $+

$

*

*

,

+ ! $!

$ $

$$

7 LI !

* !

7 7

$

$

+ !

$

" ,

8M .(AA> KAA1

-+ $

+

!

* !$

$

$L +

+

$ $

+ !

+

!

$ *M

.(AA> KAK1

+

!

2

+

+ $+

+ !

* ! $ *!!

"

!

*

$

"

"

*

+

"

!

9

"

" $7

!

4 !

$

$

$ , $

;

!

4

!

! * " $

! *" $ $

"

!

$

$ + #

!

(AAC

*

$

$

$

1

!

!

* !

$ !+ "

!

-+ $

*$

!

-$

4

!

*

$

" *

+ $+

$

?4 $

2.

"

1

!

4 !

"

!

$ $+

-$

$

* !

!"

$ * !

+

$ $+

!

"4$

"

!

$*$ +

$7

* $ $

+ ! $9

$+ $

$

2

7

*+

$ $ ! ! *" +

" "

$

/0

!

$,

!

$

2

+!

!

4 !

.

(AAA1

!

* ! $ $ 3$

7

*

!

"

$

+ ! 3

$$

*

7

! +

+ $+

.::1

+ $ $$

+ !

.:(1

$

*

++*

2 $ ! "

$

+ $+

.

"

"4$ $ 3$

1

+

#

$

$

!

$

/0

*

7

$

$

.::1

+

E

!

!

@

$

+

2

+ ! $

.(AA> C<1

$ "

, "*

+

"

.?

! 21

" 6"

$

$

$

" #

/

$

.(AA> =K1

+

7 .:;;>1

- !+

"*

+

" * .?

!

"

7

"

*

?

! 2

!

!

*

"

!

-$

"

4

$

!

*

$

"

$ !!

*

+ $+

$

M 9

$

!

,

$

"

2 #

?

$

21

3"

#

$

!

! 2#

?

+

$

+ +

$+

?

L

.:(1

$

" !

"

$+

7

!

+

. ++

"

+ *!

$

$

$

*1 $ $

$

$

+

1(

$

*

!

* + + *3

* ! !"

$

$

$

!

" I

" I

$

*

$

"

$

*

! *

* + + *3

!

+ $

*

$ $P $

$ ? 2

?$ ! 2

$

"

$

!

*

*

(:#

*

!

$

$ I

7

$ $

/0

" (

$ #$

!

$

*

I "

!

$

V

7

(

*

+

* ! $

J I+

+

< I !

!

+

3*

V "

$

$

$

! 2

!

*$

+

+

!

$

?9

$ "

++

!

* *

*

$

" "

*

!

!

$

$"

?!

$

$

!

$

$ "

$

-

!

2

$

!

7

$+

$$ $

* * !

$+

" 7

)

!

"

+

$ $

4

$ ?

!! *

:

K

-

2

.

*

* 7

$

!

+

?

*

++

!

! +

"

2

?" 2

7 *

* "

*

"*

$

! +

!

$ .

@

(AAC1

!

*

+

$

+

$ $

6 2 !

!+

2 4 !

*

$ * 7 *

+

$

!

$

$

4

$

-+

? +

+ 2 + !+

"*

$

+!

!

$ $+

" * "*

$ 2

+

*

'

$

*$

"

#

*

*

+

$

*

*

!

$ !+ - *

$ $+

!

$

$

* $

$ 2

!? 2

7

2

1+

! *$

? * !

+

!

'

*

2 !

"

+

! $ $+

!

! *+

+

!

$,

+

$ +

$+

*

+

"

! 7

"

$ !+

.

$

7

- !+

7

EG

+ $

!

+

!!

+

!

$

"

*

"

!

E G .E

$

+

!

2

'

*

!

4

+

*

$$

!

$

"

*

$

.(AA>1

' ! 7*2

$

+ $+

EG .

G !! 1

$

1 -$

!

$

!$

$

*

$ "

+

/0

*+

*

+

*

/0

"

"

!

"

,

-

$+

+ ! $

*

! $

!

7

!"

+ +

$ $

$ 7

! $

$,

9

$

!

"

" $7

$ "

! $

! $

"

" $7

. , $

1

.

1

! $ *

$

L

$ $ $

$ M .@ $7

(AA> K=1

$

+ $

$ !

*+ $ * $

$*

!

$

7

! $ ,

-$

/

H '

.(AAK >;A1

?! $

-$ 2 "

$ $

L

+

* !

$

+

+ $ $! $

+

$

"

-+

2

! M

+ $

$

! $ $!

!

+

! 7

7 7 +

$ *

7

-$ G

+

+

+ +

+

$

@ $7

2 $ !

$

! $+

*

$"

$

6

$

?! $

!2 .@ $7

(AA>1

" $! ? !

2

+ $ $ * L

$,

! $

!!

&! $

! 5

P )M

L

+ 3 $

! ! P"

! 7 +

"

$,

! $

!!

7 + $ 8M . " + KJ1

*

$

+ $ $*

! $ $+ $ *

$

-+ $ * +

$

"

9

9

+ +

+

*

$

*

1.

!+ *

5

++

5

"

L $

!

$ $

$ $

$

$

!3

+ $ $

! $ + $+

+ $+

M . " + <=1

7

+

$ "

! $

"

! 7

+ $+

++

+

! $

!

!

"* !

!

L !

+ !

+

"

$

7

+

$

+ $+

! $

!

! $3

+ $ 3

+ $ $M .

"

(AA> ;:1 6 * ! 7

*+

+ $+

$

*

* !$ $

"

+ $

. " + =<1

! $

!

+ $ 3 + $ $ . " + =C1

* !+

.

"

(AA> =(1

$

! $ +

*

+ *

*

!

* $ !! + $ +

*

+ +

"*

* !

! *" $

.$

(AAA + !1

$ ! $

5

$

$

,

C+ $

$

* !

* !"

(

K

.

(AAA:K3:J#

/ H(AA>1

.(AA< <>3<C1

+

L/ +

" "

!

!!

! $ *

*

7

* , $7*

"

+ $

$

+ +

! $M

!

* L $ !+ " *

$

! $M .

(AA< <=1

+

*+

$ + !

$

"*

.(AA< >C1

$

$ !+ " *

!

! *

$

+ $"

$

! $

! $

.

$ 1

! *"

!+ + * $ -+

* "

2

*

+ $

! $.

" (AAA1

$

+ ! $

* $

! !

! $

.

"

(AA> =>1#

+ $

! $ " * $

+

"

+ $

$

!

,

-+

$ $ +

.

(AAA:K1#

+

* !

!

+

"*

"

.

"

(AA> =(1

! $

+

L

$ $

$

$ M .@ $7

(AA> K=# " $

" 1

+

?$

!

*2

! $

! $.@ $7

(AA> J( 1

"

.(AA> =:1 +

+

!

$

$ * ++ +

$

. $

$ $ 7*

++

$ $ 7* 5

*

$

$" 1

" *

7 *+

"

10

! 7 $

$!

$

P

$

$

*

" *

$ "* !"

+ .$ @ $H*7 :;;C1

! 7

$

-+ $

+ $ $ - !+

!

$

+ ! $$ $

"

$,

+

"*

*

$

$

$

!

I

$

.

+

$1 $

.

+

$1 $

!

$ $

$

'

! $

W .

1 $

.

*1 (( X +

$

$ !!

$ "

?

$

!2 +

*

-+

! + $+

++

"

"

?

2

* $ $

" $!

"

$ $ +

. 1 "

+ $

+

$

$

$!

.

"

(AA># $ @ $H*7 :;;C1

$

!

! * "

*

+ $

$

$

+ $

! $

?

+ 2

$

$ $

$

+ $

$

,

/0

$,

"

"

.(AA>1 +

+

*

$

*+

$

$,

$

!+

$ !+ -!

L

>3!

3

7

!+

$ !+ -!

(!

*+

+

!

+

"

!+

$ !+ -!

>3!

3

2

+

! 3+

! 3

+

+

$

* :( !

+

*

! 3+

! 3

+

!+ 3!

$ - "

$ !+ -3!

$ -M

.

"

(AA> ==1

$

" /0

"*

$

*

"

"

L

* $,

7 "

+ $

* !

!

$

+

$

+!

$

*

$ $ + $

$ M.

"

(AA> =;1

+

.:K1

.:J1

!! *

E

+ $+

+

$

+ !

" K

$

*

*$

/0

.:K1

E

!

$ +

$+

+ $

$

"

$

$

$

$ #

-+

-+

#

$ $

-

$

$

+ $

+ $

2

.:J1

'

'

" '

$ '

+ !

$ !

$

$ !

!

$

! *

:

(

K

$

*7

* +

! $

*

J I+

< I !

!

"

"

*+

!

+

$

!

$,

!

$$

!

!

*.

$

$ " + $+

$

!+

!

$,

$

$

$

*

$ $ +

4 !

+!

"

$ !+

$

$

"

+

$

*+

*

1

!

+

$ "*

/0

$

!

!

$

/0

!

! $

!

+

"

!

! $

+

$ "

8

"

"

"* + $ *

!

$ "

!

$

*

$

" ! ! $*

/0

+

$

*

"

" $7

"

?

2 ? * " 2 ?+

2 ?!

?"

2

$ $

$

.

H

:;;C1

.(AA< :AJ>1 +

L'

*

$ $ *

$

* "

+

!+

$

?

2

$* ! * "

++ !

" HH

!

/0 +

!

!

$ ?"

" $7 2

-+ $

!

"

;AAA + $

" . $

JAAA + $

L

!

"

3+ $

$

$ $

$

$,

+

$ M .

(AA: J(;# $

:;;;1

!+

"

*+

$ 3 + $ " $ !+ " *

!

3+ $

!

!

.

$

*

! $

+

/ " "* + .

$ 1

V

+

++

* *

3* ! $

V

/ " "*

"

$

$7

)

$ +

$!

$

.

$

$

!

"

" $7

$

"

"

2 ? *+ 2

G

*+

!

"*

++ +

M

$

"

*

1

$+

,

!

*

1

!

+ !

!

" .

*1

?

+ !

2

!

"

:;;; (;<1 6 " $

2. $

$

$

$

*

+

"

$

"

!

+ $

+

+

$

"

+ $

*M .

? + 3

H"

$ 1

" $

+

P

-$

!

"

" $

+ $

* ! ! ! $

5

$

+

! 3

$

$

"

! *!

*

7

" $

!

$

! $

! $"

+

:A

" $

* !

$

$

$$

* $

*

+ $*

!

"*

$

"

?

$ 2

! $ !! $

.

(AAAK:1

"

$ !"

, $

! *

* "

7 !

* 9

$

- "

$

.

(AAAK;1 9

*

! $

"

"

! $

-$

"

!

"

+

* ! !

?$

2

I +

"

$

7 $ !!

+

"*

R

.:;;;1

I +

R

.:;;;1

"

+

"

$ $

* +

$,

::

+

. + $

+ $ 1

7 !

"

?

2 L*

"

!

+ $

! "

$

+

*$

*

*

"

$

+ $

!+

M.

(AAA>;1

$ !+ "

*

!

3

-+

$

3"

!

"

+

! "*+

*

+ !

!

:A

7

$ '

+ $

3

$"

+ ! $$ $

3"

/0

" !+

"

+ $ *

L

+ $

$

$

"

1

? 3 !

2. $

* "

+ !

*

$

*

?+

+

!

$ $

?/

$

23L

" * $

$ !"

!+ *

*M

? -$

23L

* $$ * 4

M .

(AAAK:1

++

*

$

?!

2

* !

"

!

! * -"

! $ $

.:;;; <:1 "

"

+ " "*

-$

+

? * " 25 +

$ $

$

::

"

$ $2 5

! 7

*

! *

+ $

* $

"

*

!

7

?*

*

-2

$

"

$

$

*

+

"*

!

!

,

!

$

* $

:AAA * "

* $$

+!

3

2$

! $

+

-$

!

"3

#+

$

" ""

*

$

!

9

R

"

"

++

? !+

2 $,

$

.$*

+

!

! !

" ,

1

.$

$ !

*

L

+

!

$ !+ "

2

? $

$ +

*

+

$

(AA<1 $

+

$

+

+

"

2 + $

$

$ !+ - !

! + M .R

:;;; J(J1

- !+

+ $+

!

$

!

"*

!

$!

* "

$

-+

+ $ $ !"

+

!

$

"

G

.(AA<1 +

$

2 " *

!

3 !

*

3 !

L +

!!

! *+ $

$ *+

M

$

?

$ 2

?

$ 2 @

$,

L

$$

"

+!

"

"

M.

:;;; K::1

$ "

+

?

$ 2 $$

$,

./

3/ !

:;=;1 L

"

$ *

! $

!

,

!

+ $ 3+ $ $

$

+

%

! ! H

"

$

% "

$ + $

!+

7

!

,

$ + $ M.

:;;; K:<1

+

" *

$,

$

!!

$ !

.G

(AA>#

$ (AA># $ @ $7

(AA>1

+

$ "

$,

$ !+ - $

!!

L$

&)

$ $ !

$

!

$ !+

$

, * !

$ *

.9 1M .G

(AA> :(A>1

$

$ "* @ $7

2 .(AA>1 "

$ ! $

"

"

"

$

!+ $

$

+

"

"

"

!

7

.

$ 1

.

$ 1#

"

$ .

' $+

:;;:1

$*

$7 .:;;;1 +

!

"* $

+

+ *

$

+

$

$ + $ $ !

V 7

/

*

* !+

L

+ $

+

$ $ $

$ $ M . " + <;:1

+

+ $

/

! "*

+!

$

$ $ * +

$

+ $ +

+

"

$ $ $

*

$ $

$

*

$

/0

*

$

$$

$ $ +

$ $

$

?!

2

$

$ !+ "

/0 "

$

"* H "

.(AAJ1 !

$

$

$

"

L! !"

! $ $

*

!

M .(AAJ :=:C=1 ' $ *

4

.(AAJ :=:=A1

? ! 2

7

$ !+ "

$

$,

+

*

$

$ $ $ $

.$ I +

:;;;1

" J

$

:

$

* V

!

7

(

K

$

*

V

+

* ! $*

!

!+

+

< I

!

/

!

7

$

"

$7 :;;;1

$ .

!

!

!

* $

7

! *

$ /0 + *

U !+

$

G

V

.

$7

"

$

"

"

++

!

"

!

.(AA<1 +

+ $+

$

L +

!! M "* $

*

+

!!

L $$

" $

* -+

! $ *

M

$ $

L

$

$ !+

+

!!

!

M .(AA< :AJC1

!

"

$ !+ "

/0

!

+

*

7

$ $

$

+!

"

"

$

! *

+ 3 +

$

!

+

$

+ ! $"

$ !+ "

$

! *

" 4

!

$

"*

.(AAJ1 ! 7

"*$

4

"

* $

+

J I+

!

+ $

/0

$

!+

/0 ! *

7

!

-

$

*

1

*+

$

.' $ +

*

3

$,

!! ! * "

$

$

:;;: (==# $

$*

$

$ $

$

*

$ !+ - *

! *"

"

"* -+

,

!

! *

"

$

/

2 + " !

$+ $ !

$

'

+

,

!

/0

2 $ !

$ $

8

#(

"*

.:<1

/0

" /0

$ /0

$

/0

!"

,

,

$ !!

!

!

"

*

$

"

"

"

"

$

!1

-$

H

!!

4

5

.

$

/0 $

"

!

$ !!

$

.9

+

%

/0

$ +

"

"

"

!

$

.1

1

! $

+

$

"

' $ +

! *"

"

$

*

"

$ *

$

/0

*+

* $ $

/0 $ "

$

!

*

$"

!

!

!

4 !

! $

"

!

"

$

/0

$

/

2

+ " !

$

*+

*

$,

$ $

++

! $!

4 !

"

+ $

++

5

. 1 "

$ $ "

$

!

$7

! $

!+

/0

!

! $

!

"*

"

$

$7

$ $

+

$

. * $ $1 /0

!

-$

$ !+ " $

$

! $

$ $

!

4$

+

! $. 1 "

"

*

7

*+

$

2 .:;;K :1 +

/0

:(

. 1

$

++

!

+

,

V

/0 "

,

8

+ $

" ! *

$ !+ !

:(

$,

M .:;;K J1#

$

2 $ !

LEG $

$ !

:;;A

*

$

! 7 " * $ !+ $

$ !+ - *

$ ! 7 /

!

+

$ !+ !

*

! +

*1 $

#+ *

@ $7

.(AA>1 +

*

$"

* $

$

"

!

$

+

$

+

* -M

+ * /0

$ $ * *+

*

$,

$

$

!

" 7

+

" $ $

2 + " !

$

+ * ."

L& ) ,

3 ! ! ! *

+

$

*

0$

$7 !

/

/

$

!!

9

!

.

1 .(AA>1

66E

*/

7

.:;;>1

%%

:

V 7 6E/

@ .(AA<1 LI

+!

"

M

@

3 G

#

9

;

)<

) "7#

5 6$7

@

$+

.(AA:1 L $ ,

$ *

" =

#

< J(>3JKK

H

I

R

.:;;C1 Y

$

"

* !L *

9>

%KK J;<3<AA

7

.(AAA1 L

$

*!

7

. 1

?

9

' !"

(J

' $+

' .:;;:1 L

M

7

7

. 1

=

"

9?

%# ' !"

'E/# ++ (=K3(;:

' ! 7*

.:;C:1 L6

+

M=

" @ # ;( CC5;K

' ! 7*

.:;C<1 @ 9

V 7/

' ! 7* .:;=A1 @

"@

5 6$7

' ! 7*

.:;=: 1

A #

" " 5I

$ 9

' ! 7*

.:;=:"1 L/ $+

+ !

* $$

*M

.

1 7B

5

! :(K5:J>

' ! 7*

.:;=>1 C

" 9

; >

)?

"D

V

' ! 7*

.:;;<1

:

' !"

/

' ! 7*

.(AA(1 ? >

"

' !"

'E/

' ! 7*

.(AAK1 :

"

; : 40 11

$

"

#

/

' ! 7*

.(AA>1

"

" 5 ' !"

'E/

I +

/ R

.:;;;1 L

+ $ ' !!

!

! $

@#

9>

(( <>C3>K:

I +

.:;;;1 L

3

3

$

* +

!

"

"

$

M

R

9

=

' !"

/

# ++ KJK3K>=

I

.:;;;1 L'

+

'

+ !

M

KA(C3>C

"

. 1

# ++ ::;3:J<

! ! *M

$

/

*M

# ++ K3

7 %

"

I

7/

V 7

!M

.

1

E %

(

I

@ R * .:;;A1 L $ !+

!

! $ +

*M

=

KJ :KC3:;<

9

G .:;;K1 L

+

$

!

$

+ !

M# G 9

. 1

:

/

9D #

A

F !

! @

4! # ++ 39

@ .:;C<1

9

5

V 7'

G

9

9

" ! .(AA<1 L9

!

$,

+

!!

" 2

M

KA= :AJ>3:AJ;

G

R 9

I

" ! .(AA>1 LB $

* $ $+

"*

" M >

JJA:(AJ3:(AC

.:;;K1 L/ $+

" * / ! H

+ !

- M

G

9

. 1

:

/

9D #

A

F !

! @

4! #

++ :3:>

/ .(AAA1

6 $ 9

5

.:;;C1 L

"

$+

M

B *

. 1

#

;7B

"7#

' !"

'E/# ++ ::(3:JK

.(AA>1

"

V 7#

+ '

' ! 7*

$!

9 $ .(AA(1 L

$ *

8M

(;= :<>;3:<C; .

!" ((1

9' !

V

B R 3Z @

@ 7

.(AAC1 L

$

"

!

4 !

4

$

M

"

(( :3(:

4!

.:;>:1 :

% 9

5

E

*

$

/

$7 ' .:;<=1 =

"

5

* !

.:;=C1 L

*

+ !

* $$

+! M

B +

! . 1:

#I

$ B

# ++ :3((

@ $7

B 9

.(AA>1 L $ + $ *

! $

2 + $ "

8M =

:AAKK3C(

@ $7

B

" !

G /

!

$ H .(AA>1 L

* B$

M

+P

P

P

P

:CP

:C3:<(= !

@

I .(AAC1 L

+

M >

@ :J (AAC# ++ C>=3CC:

@

. 1 .:;<C1 @ "

5' $

E

* ' $ /

@ $H*7 / .:;;C1

# % 9 $

5 ' !"

/

R*

B .(AA<1 L !

$ !+

* + $

$

9 $M

G ' ,

B R* . 1

?B9 " G " $ 9=

# % B)

66E/# ++ K3>;

R

/ .:;;;1 L + $

"

+ +

M

R

. 1

9

=

' !"

/

#

++ J:;3J<A

7 G .:;;>1

:

' $ #E

* ' $ /

G

9

" ! .(AAJ1 L@

H"

$ $

! +

!

M :> :A: :=:CC3:=:=(

H

B

.(AAC1 D 9

9

% " % B5

B

$ G .(AA>1 L

M >

JJA:::C3:::=

/ .:;;;1 L6

+

?

2 ?

28M

R

. 1

9

=

' !"

/

# ++ (;K3K:=

/ .(AAA1 L6

! $

+ $

!

! M

7

. 1

?

9

' !"

/

# ++ K:3J=

7

@ .(AAC1 LE

!

!!

*

$

M

"

=

#

:: :JK3:<(

+

/ .:;;;1 LG

$

$ *

! $

!

"

$ $

M

R

. 1

9

=

' !"

/

# ++ K>;3K=;

*7 / . +

1<

=

' !"

'E/

.(AAA1 L

! $

$ !+

! $

! $

$

M

7

. 1

?

9

' !"

/

# ++ J>K3JC(

.(AA<1

"% 97

%;

%4

"=

5 E"

E

*

/

/ H .(AA>1 L

! $ ! "

$ + + $ M=

:AA :3K(

/ H

'

.(AAK1 L

* ! $+ $

M >

>

> >==3

>;:

/

3/ !

.:;=;1 L

$

$

!

+ !

"

*

*

M=

K: :5JJ

/ 7

.:;=J1

% "

5 ' !"

E

*/

/ ! G

@ B *$7 .(AAC1 L/

3 $

$

$ * !

M

B"

.:;;C1 =

# % B

B"

B

.(AAK1 %

=

;

A

/

5 ' !"

'E/

R .:;=C1 L' !!

H M

B +

! . 1:

#I

$ B

# ++ CC3=;

*

9 I $7

.(AA<1 L

3

7 $

*+ $

"

"

!

!

*

M

# @

" KC ;;3::A

$*

$7 .:;;;1 L9 $

+

M

R

. 1

9

=

' !"

/

# ++ <CC3

<;<

!

0 .:;CK1

E

9:

%; =

"%5 ' !"

'E/

!

0 .:;;A1 F' + ! $ - + !

8F

B$ . 1

E

9

++ (CC3(=;

!

0 .:;;;1 L

$

M A

J < ; .B +

!

(AA(1

!

0 .(AA(1

)

"

;

:

) : //

"

:

5 6$7

!

0 .(AAJ1 =

$%; "

""

.(

1# ' !"

'E/

!

0 .(AA<1

)<

" # ;

:

): //

"

:

5 6$7

!

0 .(AAC1 LE $

* ' ! 7*2

M =

$%

" ( :3

(:

!

0

' ! $7.(AA(1 L/ ! $+

*M A

> (=<3(=C B +

! .(AA<1

B .:;;;1 L

!

"

$ +

! $

" M

R

. 1

9

=

' !"

/

# ++ KC3>(

!

.(AAC1 LB $

$

* $$

*M

::C :C=J3:=AA

"

.(AAA1 L ! + $

+

+

! $

M

7

. 1

?

9

' !"

/

# ++ J(C3JJ=

"

.(AA>1 L

! $+ $ +

I ! 3

! 3+ $ $

! $

! 8M =

:AACK3;;

.

' .(AAA1 L

7

C>

V+

.(AAK1 L'

2 "

.

"

1

8

?

6

3B !

"

9

"

/

' !"

$

M

::K CC;3=:>

M

# ++ ><3

Phonology

ATR allophones or undershoot in Kera?

MARY PEARCE

Abstract

Kera (a Chadic language) has 6 vowels, 3 of which have +/-ATR allophones. [+ATR]

vowels appear in non-heads of feet and [-ATR] vowels in heads and elsewhere. This

binary classification is sufficient until we examine the acoustic measurements of F1, F2

and duration in footed and non-footed syllables. These results suggest that the variation

in quality relates to the duration of the vowel rather than directly to the foot structure. We

will consider the evidence for claiming that there is a gradient relationship between the

F1 value and the duration. The key data for this claim come from vowels in non-footed

syllables at the right edges of phrases and vowel initial syllables. In non-footed syllables

the duration of the vowel is longer than a non-head vowel, but shorter than a head vowel.

The F1 value for these vowels is equally between the average head and non-head values.

Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006) have demonstrated similar patterns in other languages

where a shorter duration means a more centralised vowel. Their results could lead us to

suppose that the reason for this gradient is articulatory, due to the need of a certain

amount of time for articulators to arrive at the target position, and that all languages may

exhibit a similar phonetic pattern. A few counter-examples suggest that this pattern can

be over-ridden by phonological factors. In the case of Kera we may well be seeing a

process that began as a gradient phonetic change but which is now in the process of being

phonologized. Therefore the use of the term ‘allophone’ correctly describes the

phonology, but the phonetics also has a role to play in the quality of the vowel.

1 Introduction

Kera has been analysed in the literature (Ebert 1974, 1979, Pearce 2003) as having 6

vowels, 3 of which have +/-ATR allophones based on the position of the syllable in

the iambic foot. [+ATR] vowels appear in non-heads of feet and [-ATR] vowels in

heads and elsewhere. Up to now this binary classification has been generally accepted.

However, a closer inspection using acoustic measurements of F1, F2 and duration

reveals that the variation in quality may be due principally to duration rather than foot

structure (although the foot structure affects duration). This would lead us to suppose

that rather than a categorical distinction between the allophones associated with head

and non-head syllables, we may have a gradient relationship between the F1 value and

the duration. Both increase together until the target F1 value is reached, at which point

a further increase in duration no longer affects the quality. The key data for this claim

32

Mary Pearce

come from vowels in non-footed syllables at the right edges of phrases and vowel

initial syllables. In both of these cases, the duration of the vowel is longer than a nonhead vowel, but shorter than a head vowel. The F1 value for these vowels is equally

between the average head and non-head values. Neither of these cases fits neatly into a

binary division of allophones.

A useful comparison can be made with French. Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006)

have measured F1, F2 and duration in corpuses from several languages including

French, and conclude that in each language the F1 and F2 values appear to vary with

duration in a gradient relationship, particularly in non-high vowels. They observe that

the polygons made by the vowel space in an F1/F2 plot converge as the duration

decreases towards a schwa like vowel. Kera shows a similar convergence, but towards

a horizontal line rather than a point. For a full understanding of the Kera facts, we

need to combine an undershoot account with a consideration of the effects of the

metrical structure on duration and the contribution made by the rich vowel harmony

system, which may be constraining the variation in F1 and F2.

This paper begins by looking at the case for allophones and the case for undershoot.

We then move to consider other languages as mapped out by Gendrot and AddaDecker, and we compare the Kera results with these languages. Finally, we will

discuss whether the Kera facts are best considered as a categorical split between

allophones or a gradient of qualities that vary with duration.

2 The case for allophones

Kera is typical of a number of Chadic languages in having a symmetrical system of

vowels which can be paired into high and non-high vowels. Kera has 6 vowels, and

the three high vowels do not differ much in quality regardless of the duration or

position of the vowel in the foot. But the 3 non-high –ATR vowels have +ATR

allophones in non-heads of iambic feet1. This binary analysis of these vowels gives us

[+ATR] vowels in non-heads of feet and [-ATR] vowels in heads and elsewhere2.

1

More information on iambicity in Kera is available in Pearce (2006).

The use of [ATR] rather than [tense/lax] is not meant to be significant. Either could be used in

Kera. It is important however that this feature is differentiated from the high/non-high distinction

which is contrastive, playing a role in height harmony. Casali (2001) supports the use of the [ATR]

feature in this case even if the action of the tongue root is not proven, but it should be noted that in

most African languages when [ATR] is involved, it is used to mark contrasts in an ATR harmony

system.

2

ATR allophones in Kera 33

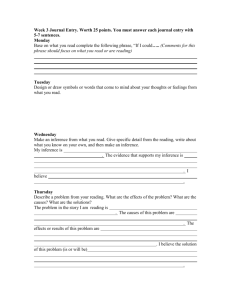

(1) Allophones in Kera vowels

Phonemes:

/i/

Head (-ATR)

[i]

Non-head (+ATR)

/ɨ/

/u/

/ɛ/

/a/

/ɔ/

[ɨ]

[u]

[ɛ]

[e]

[a]

[ə]

[ɔ]

[o]

In (2), the three non-high vowels are split by a dotted line separating the allophones.

(2) Means of footed Kera vowels for 12 speakers

F2

2500

2300

2100

1900

1700

1500

1300

1100

900

700

250

i

i

i

i

i

i ii

i

i

i

i i

i i i

i

i i

ii

i

i

e

e

e e

Non-head /ɛ/

[+ATR]

e e

ɛ

ɛɛ

ɛ

u

ɨ

i

ɨ

e

u

ɨ

ɨ

ɨ

ɨɨ ɨɨ

ɨ

ɨ ɨɨ ɨɨɨɨ ɨ

ɨ

ɨ

ə

u

u uu

u

u uə

ə

ɨ

ə

ə

ɛ ɛ ɛ

ɛ

ɛ ɛ

ɛ

ə

ɨ

ɨ

e

u

ə ə

o

ə

əəə

ɔ ɔ

ɔ

uu

uu u

u u o

u uu

u

o u

o

o

oo

o

o

ɔ ɔɔ ɔ

ɔɔ

ɔ ɔ

ɔ

300

u

o

350

400

o

450

500

550

Head /ɛ/

[-ATR]

aa

Non-head /a/

a

[+ATR]

Head /a/

[-ATR]

a

a

aa

a

600

a

a

a

Non-head /ɔ/ Head /ɔ/

650

[+ATR]

700

[-ATR]

a

750

F1

Because the ə/a alternation involves two allophones that are phonetically much further

apart than the others, Ebert (1979) treated this alternation as a special case of a process

of dissimilation which changed every other /a/ into [ə]. This alternating pattern was

actually the result of the metrical structure which prefers disyllabic feet where nonheads and heads will be alternating. Unfortunately the apparent special case for the

low vowel /a/ has led several linguists including Buckley (1997), Suzuki (1998), de

Lacy (2004) and Archangeli and Pulleyblank (2007) to give this Kera example as

support for theories of dissimilation processes involving low vowels, although all of

these authors cite other languages as well as Kera. But this alternation behaves exactly

like the alternation for o/ɔ and e/ɛ, and the three pairs should be treated in the same

way.

Examples of the allophones can be seen in the following words where feet are

indicated by parentheses and head vowels are underlined. In these examples, there is

34

Mary Pearce

total vowel harmony, so any change in quality is due to the choice of allophone for the

position within the foot.

(3) Allophones chosen by the position in the foot (head vowels underlined)

(gədaa)(yaw)

(dak)(təlaw)

(sɛɛ)(renɛn)

(gɔl)(donɔn)

‘pots’

‘bird’

‘rescued me’

‘searched for me’

Kera is not alone in having such alternations between stressed and unstressed

syllables. Among Chadic languages, Pearce (2007) notes that Hausa (Newman 2000),

Sokoro, Goemai, Bade and Ngizim show a similar pattern. Beyond Chadic, there are

languages such as Catalan (Harrison 1997) which has a 7 vowel system /i, e, ɛ, a, ɔ, o,

u/ which reduces to 5 vowels. [ɛ] and [ɔ] ([-ATR]) appear only in stressed syllables.

Returning to Kera, as long as we consider only the vowels contained within feet, this

analysis appears to be perfectly adequate and the case for a binary choice between

allophones seems solid. However, if we look at vowels that are either unfooted or

epenthetic, the case becomes less clear.

3 The case for gradiency

Our key evidence for gradiency is that non-footed vowels have a duration and F1

value between head and non-head vowels. They do not fit neatly into either of the two

categories. Non-footed syllables are found at the right edges of phrases and in vowel

initial words where the syllable is made up of just the vowel. These vowels do not

behave like the vowels in footed syllables. The table in (4) demonstrates this, also

including epenthetic vowels which equally do not fit well in a categorical system. The

quality that we previously called +/-ATR does not seem to vary according to inclusion

in a foot or headedness. It does however appear to relate to the duration of the vowel.

The shortest vowels are closer to a [+ATR] category and the longest vowels are closer

to a [-ATR] category. There is the temptation to argue that this is still a categorical

distinction between short and long vowels, but all the vowels in (4) are phonologically

short. Kera has a phonologically long vowel which has not been mentioned. This

vowel typically has a duration of around 110 ms with a quality in keeping with the

feature [+ATR]. But the difference in quality in (4) appears to occur at around 50 ms

which is not the same place as the phonological boundary between short and long.

ATR allophones in Kera 35

(4) The correlation between quality, duration and position

Head V

Not a Head V

Epenthetic V

Head V Non-head V

Non-footed V

(tar) ‘run’ (cəwa:) ‘sun’ (gɔl)do(tonɔn) (baa)ŋa ‘elephant’

Footed

?

Duration 70ms

30ms

30ms

50ms

+ATR

?

So instead of a categorical distinction between the allophones associated with head

and non-head syllables, we might find that positing a gradient relationship will suit us

better. As the phonological feature [ATR] is categorical, it does not lend itself to being

treated as a gradient. Instead, we will consider the gradient in terms of the F1 value. In

(5), the non-high vowels are plotted on a graph with F1 against duration. The mean

values for vowels in each category are shown. Non-heads are short and the F1 value is

also low. Heads on the other hand have a much greater duration and a much higher F1.

The non-footed vowels have a duration between the footed vowels already considered,

and likewise the F1 value is between that of the others.

(5) A gradient change in duration and F1 (diagram in Pearce forthcoming)

700

Heads

650

/a/

Non-footed

600

Non-heads

F1 Hz

550

500

/ /

/a/

450

/a/

/ /

400

25

35

/ /

/ Ɔ/

/ Ɔ/

/ Ɔ/

45

55

65

75

duration ms

It seems that duration and the F1 value increase together until the target F1 value is

reached, at which point a further increase in duration no longer affects the quality. The

curved line in (5) is there as an indication of the gradient nature of the curve. These

data are not enough to give any precise equations for this line, but the implication is

that the vowel has to be of a certain duration before the F1 target can be reached and

36

Mary Pearce

that if it is shorter than this, the vowel will have a reduced quality. The reason for this

could well be that the articulators do not have enough time to reach the target.

So the analysis of a gradient curve rather than an allophonic split now seems the

better option. We now consider other languages to see if there is evidence for a similar

gradient curve there.

4 Convergence in other languages

For this section, we will make use of the work of Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2005,

2006). They have studied eight languages, using a large corpus for each, and they have

found similar results in each language. In the diagrams below, I include only the

vowels which bear some correspondence with the Kera vowels, but the results with all

of the vowels in each language are available in the original papers. My purpose here is

to demonstrate the trend that appears to be present in all of the languages studied. For

each language, a plot of F1 and F2 is made with different polygons according to the

duration of the vowel. The results show clearly that F1 and F2 values vary with

duration in a gradient relationship, particularly in non-high vowels. The polygons

made by the vowel space in an F1/F2 plot converge as the duration decreases. Gendrot

and Adda-Decker suggest that the explanation for the convergence effect might be

partly articulatory. This view would be supported if all languages converge in the

same way. This is true in their data. Four language plots are given here.

(6) Measured mean average values of F1 and F2 for French vowels according to

duration, data from Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006), selected vowels only

F2

2400

2200

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

200

<60 ms

u

ø

i

300

500

ɔ

ɛ

600

60-80 ms

>80 ms

700

a

800

F1

400

ATR allophones in Kera 37

(7) Measured mean average values of F1 and F2 for English vowels according to

duration, data from Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006), selected vowels only

F2

2400

2200

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

200

300

i

u

e

500

<60 ms

o

F1

400

600

60-80 ms

700

æ

a

>80 ms

800

(8) Measured mean average values of F1 and F2 for German vowels according to

duration, data from Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006), selected vowels only

F2

2400

2200

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

200

y

u

i

300

500

<60 ms

e

o

60-80 ms

>80 ms

600

700

a

800

F1

400

38

Mary Pearce

(9) Measured mean average values of F1 and F2 for Mandarin vowels according to

duration, data from Gendrot and Adda-Decker (2006)

F2

2600

2400

2200

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

800

600

200

300

i

400

u

e

600

o

<60 ms

700

60-80 ms

800

F1

500

900

>80 ms

a

1000

The other languages measured by Gendrot and Adda-Decker giving similar results

were: Arabic, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese. The question arises whether it is

possible to claim the same kind of vowel reduction for all languages. At first glance

there appear to be counter-examples in the work of Archambault and Maneva (1996)

and Gussenhoven (2004). The first of these studies considers devoicing in post-vocalic

Canadian-French obstruents. Other cues for devoicing were measured, including the

vowel duration and quality. They make the observation that lax vowels, which appear

before voiceless obstruents are shorter, while tense vowels, which appear before

voiced obstruents are longer. This would seem to be the inverse of the diagrams above.

However, as the sample included both high and non-high vowels, and as separate

results are not given, we cannot compare this study with that of Gendrot and AddaDecker. This study also refers only to vowels before obstruents where the voicing is

known to affect a number of cues. So the results could be different if a more

comprehensive study of vowels in all positions were made. A similar comment can be

made for the Gussenhoven study on Limburgian dialects of Dutch and English coda

obstruents. The results seem to be the inverse of what we are expecting, but this study

is again looking at specific cases where a phonological contrast is being cued by the

duration and quality of the vowel. Gussenhoven notes that high vowels are perceived

as longer than non-high vowels, possibly compensating for the inverse relationship in

ATR allophones in Kera 39

production. Maddieson (1997) and Catford (1977) claim that high vowels tend to be

shorter than non-high vowels in production because the articulators are already in

position making it easier to move on to the next consonant. These results show that the

relationship between duration and quality can be affected by a number of factors.

Clearly, we certainly cannot assume that every language behaves like the eight tested

by Gendrot and Adda-Decker, and it seems that the trends can be reversed where

phonological contrast plays a role, but their work merits further research, and a useful

development would be to look at more non-Indo-European languages.

We now turn to consider what the plot would be for Kera. It is not possible to use

the same size of corpus, but nevertheless, the following plot gives significant

differences between the three polygons.

(10) Measured mean average values of F1 and F2 for Kera vowels according to

duration

F2

2400

2200

2000

1800

1600

1400

1200

1000

ɨ

i

800

600

200

u

300

400

500

ɛ

50-70 ms

strays

<50 ms

non-heads

a

>70 ms

heads

F1

ɔ

600

700

800

Kera shows a similar convergence to that found in the other languages, but only in one

dimension. The convergence is towards a horizontal line rather than a point. The

variation is most striking for the /a/ vowel. As with French, high vowels are relatively

unaffected by duration. But unlike French, the F2 value is also unaffected by duration.

The Kera result makes the articulatory explanation less appealing, but it is hard to find

another explanation. A categorical phonological explanation does not appear to fit the

40

Mary Pearce