From: AAAI Technical Report FS-02-02. Compilation copyright © 2002, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Trust in computer technology and the implications for

design and evaluation

John D. Lee and Katrina A. See

Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering

University of Iowa

Iowa City, IA 52242

Abstract

Computer technology is pervasive and often problematic,

and the sociological construct of trust has emerged as an

important intervening variable to describe reliance on

technology. Trust is an important mechanism for coping

with the cognitive complexity that accompanies increasingly

sophisticated technology. Because of this, understanding

trust can help explain reliance on technology and human

performance in complex systems. This review characterizes

trust by summarizing organizational, sociological,

interpersonal, and neurological perspectives.

These

perspectives provide a clear definition of trust, account of

how individual differences influence trust, and describe how

characteristics of technology affect trust. A conceptual

model integrates these findings and highlights the

importance of closed-loop dynamics, the role of context,

and the influence of display characteristics. This model has

important implications for how systems should be designed

to calibrate trust and encourage appropriate reliance.

Design and evaluation of technologically intensive systems

should consider the calibration of trust if they are to be

effective.

The growing cognitive complexity that

accompanies computer-mediated collaboration and multiagent automation makes understanding trust increasingly

important.

Introduction

Sophisticated information technology is becoming

ubiquitous, appearing in work environments as diverse as

aviation, maritime operations, process control, motor

vehicle operation, and information retrieval. Automation

is information technology that actively transforms data,

makes decisions, or controls processes. Automation

exhibits tremendous potential to extend human

performance and improve safety, however, recent disasters

indicate that it is not uniformly beneficial. In one case

pilots, trusting the ability of the autopilot, failed to

intervene and take manual control even as the autopilot

crashed an Airbus A320 (Sparaco, 1995). In another

instance, an automated navigation system malfunctioned

and the crew failed to intervene, allowing the Royal

Majesty cruise ship to drift off course for 24 hours before it

ran aground (Lee & Sanquist, 2000). On the other hand,

people are not always willing to trust in automation.

Operators rejected automated controllers in paper mills,

undermining the potential benefits of the automation

(Zuboff, 1988). As information technology becomes more

prevalent, poor partnerships between people and

automation will become increasingly costly and

catastrophic.

Misuse and disuse describe poor partnerships between

automation and people (Parasuraman & Riley, 1997).

Misuse refers to the failures that occur when people

inadvertently violate critical assumptions and rely on

automation inappropriately, whereas disuse signifies

failures that occur when people reject the capabilities of

automation. Misuse and disuse are two examples of

inappropriate reliance on automation that can compromise

safety and profitability in many situations. Understanding

how to mitigate disuse and misuse of automation is a

critically important problem with broad ramifications.

Understanding the role of trust in human-automation

relationships may help address misuse and disuse.

Several lines of recent research suggest that misuse and

disuse of technology depend on certain emotions and

attitudes of users, such as trust. In particular, many studies

show that humans respond socially to technology and treat

computers as they would other human collaborators. For

example, the similarity attraction hypothesis in social

psychology predicts people with similar personality

characteristics will be attracted to each other. This finding

also predicts user acceptance of software (Nass, Moon,

Fogg, Reeves, & Dryer, 1995; Reeves & Nass, 1996).

Software that displays personality characteristics similar to

those of the user tends to be more readily accepted.

Similarly, the concept of affective computing suggests that

computers that can sense and respond to user’s emotional

states may greatly improve human-computer interaction

(Norman, Ortony, & Russell, in press; Picard, 1997). In

considering emotion in the design of technology, designers

must recognize that techniques that increase acceptance or

trust do not necessarily improve performance. The critical

challenge is to calibrate trust to encourage appropriate

reliance.

Trust seems particularly important for understanding

human interaction with automation. More generally, the

construct of trust and credibility may also apply to

computer-mediated collaboration, where a person may

work with automation, multiple automated agents, or other

people through automated intermediaries. Trust and

credibility become important when computers play an

active and visible role in mediating how people interact

with data or the environment (Tseng & Fogg, 1999).

Considerable research has shown that trust is an important

attitude that mediates how people rely on each other

(Deutsch, 1958; Deutsch, 1969; Rempel, Holmes, &

Zanna, 1985; Ross & LaCroix, 1996; Rotter, 1967).

Sheridan has argued that just as trust mediates the

relationships between people; it may also mediate the

relationship between people and automation (Sheridan &

Hennessy, 1984).

A series of experiments have

demonstrated that trust is an attitude toward automation

that affects reliance, and that it can be measured

consistently (Lee & Moray, 1992; Lee & Moray, 1994;

Lewandowsky, Mundy, & Tan, 2000; Moray, Inagaki, &

Itoh, 2000; Muir & Moray, 1996).

Trust and Complexity: Organizational,

Sociological, and Interpersonal Perspectives

Researchers from a broad range of disciplines have

examined the role of trust in mediating relationships

between organizations, between individuals and

organizations, and between individuals. Specifically, trust

plays a critical role in interpersonal relationships, where

the focus is often on romantic relationships (Rempel et al.,

1985). Exchange relationships represent another important

research area, where the focus is trust between

management and employees and supervisors and

subordinates (Tan & Tan, 2000). Trust has an important

role in organizational productivity and strengthening

organizational commitment (Nyhan, 2000). Trust between

firms and customers has also become an important

consideration in the context of relationship management

(Morgan & Hunt, 1994) and internet commerce (Muller,

1996). Researchers have even considered the issue of trust

in the context of the relationship between organizations

such as multinational firms (Ring & Vandeven, 1992),

where cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural collaboration is

critical (Doney, Cannon, & Mullen, 1998). Interest in trust

has grown dramatically in the last five years as many have

come to recognize the importance of trust in promoting

efficient transactions and cooperation. Trust has emerged

as a central focus of organizational theory (Kramer, 1999),

has been the focus of a recent special issue of the Academy

of Management Review (Jones & George, 1998), a

workshop at Computer Human Interaction 2000 (Corritore,

Kracher, & Wiedenbeck, 2001), and a book (Kramer &

Tyler, 1996).

The general theme of the increasing cognitive complexity

of work explains the recent interest in trust. Trust tends to

be less important in well-structured, stable environments

such as procedure-based hierarchical organizations, where

an emphasis on order and stability minimize transactional

uncertainty (Moorman, Deshpande, & Zaltman, 1993).

Many organizations, however, have recently adopted agile

structures, self-directed work groups, and complex

automation, all of which make the workplace increasingly

complex, unstable, and uncertain. Because these changes

enable rapid adaptation to change and accommodate

unanticipated variability, there is a trend away from wellstructured, procedure-based environments. These changes

have the potential to make organizations and individuals

more productive, but they also increase cognitive

complexity and leave more degrees of freedom to the

person to resolve. Trust plays a critical role in people’s

ability to accommodate the cognitive complexity and

uncertainty that accompanies these changes.

Trust helps accommodate complexity in several ways. It

supplants supervision when direct observation becomes

impractical, and facilitates choice under uncertainty by

acting as a social decision heuristic (Kramer, 1999). It also

reduces uncertainty in estimating the response of others to

guide appropriate reliance and generate a collaborative

advantage (Baba, 1999; Ostrom, 1998). Moreover, trust

facilitates decentralization and adaptive behavior. The

increased complexity and uncertainty behind the increased

interest in trust in other fields parallels the increased

complexity and sophistication of automation. Trust in

automation guides effective reliance when the complexity

of the automation makes a complete understanding

impractical and when the situation demands adaptive

behavior that cannot be guided by procedures. For this

reason, the recent research on trust provides a rich

theoretical base for understanding reliance on complex

automation and, more generally, how it affects computermediated collaboration that involves both human and

computer agents.

The Dynamics of Trust

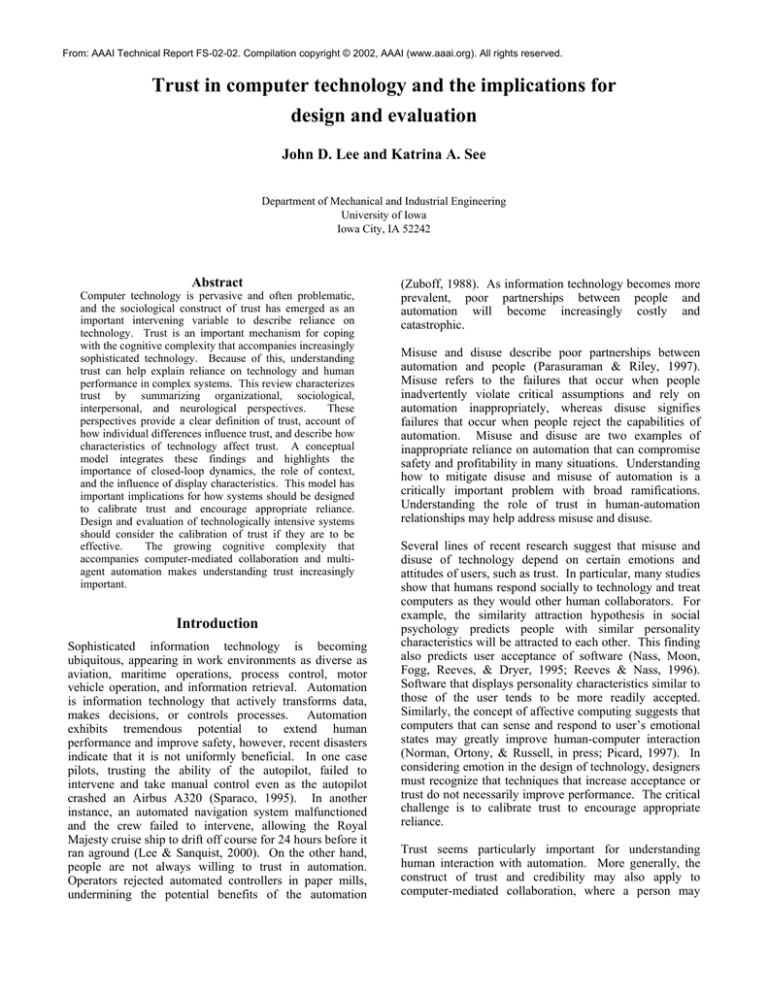

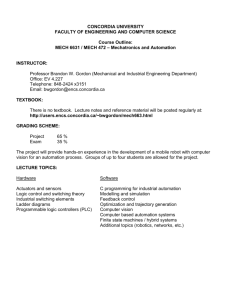

Figure 1 summarizes the factors affecting trust and the role

of trust in mediating reliance. The grey line that links the

level of trust to the performance of the automation

highlights calibration of trust as a central consideration for

guiding appropriate reliance. There are four critical

elements in this framework: the relationship between trust

and reliance, the closed-loop dynamics of trust and

reliance, the importance of context in mediating trust and

its effect on reliance, and the role of information display on

developing appropriate trust. The research addressing trust

between people provides a basis for elaborating this

framework to understand the relationship between trust and

reliance.

Trust and reliance: Belief, attitude, intention and

behavior

Understanding the nature of trust depends on defining the

relationship between dispositions, beliefs, attitudes,

intentions, and behaviors. These distinctions are of great

theoretical importance because multiple factors mediate the

process of translating an attitude into a behavior.

Considering trust as a behavior can generate confusion by

attributing effects to trust that are due to other factors

affecting intention or reliance (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980;

Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). An approach that keeps

attitudes, intention, and behavior conceptually distinct

provides a strong theoretical framework for understanding

the role of trust in automation.

According to this framework, beliefs represent the

information base that determines attitudes. An attitude is

an affective evaluation of beliefs that serves as a general

predisposition to a set of intentions. Intentions then

translate into behavior according to the environmental and

cognitive constraints a person faces. According to this

logic, definitions of trust should focus on the attitude rather

than the beliefs that underlie trust or the intentions or

behaviors that might result from different levels of trust.

Considering trust as an intention or behavior has the

potential to confuse the effect of trust on behavior with

other factors such as workload, situation awareness, and

self-confidence of the operator (Lee & Moray, 1994; Riley,

1989). No direct relationship between trust and intention

or behavior exists because other psychological and

environmental constraints intervene. Trust is an attitude

that influences intention and behavior. Figure 1 shows that

trust stands between beliefs about the characteristics of the

automation and the intention to rely on the automation.

Individual and Environmental Context

Factors affecting

automation performance

Workload

Effort to engage

Self-confidence

Reputation

Interface features

Time constraints

Configuration errors

Predisposition to trust

Information assimilation

and Belief formation

Knowledge-based

Rule-based

Skill-based

Trust

Intention

Reliance

Appropriateness of trust

Calibration

Resolution

Temporal specificity

Functional specificity

Automation

Display

Information about the automation

Attributional abstraction (purpose, process and performance)

Detail (system, function, sub-function, mode)

Figure 1. A conceptual model of the dynamic process that governs trust and its effect on reliance.

The cognitive processes associated with trust

The information that forms the basis of trust can be

assimilated in several qualitatively different ways. Some

argue that trust depends on a calculative process; others

argue that trust depends on the application of rules. Most

importantly, trust also seems to depend on an affective

response to the violation or confirmation of implicit

expectancies. The affective and calculative aspects of trust

depend on the evolution of the relationship between the

trustor and trustee, the information available to the trustor,

and the way the information is displayed.

A dominant approach to trust in the organizational sciences

considers trust from a rational choice perspective (Hardin,

1992). This view considers trust as an evaluation made

under uncertainty in which decision makers use their

knowledge of the motivations and interests of the other

party to maximize gains and minimize losses. Individuals

are assumed to make choices based on a rationally derived

assessment of costs and benefits (Lewicki & Bunker,

1996). Williamson (1993) argues that trust is primarily

calculative in business and commercial relations and that

trust represents one aspect of rational risk analysis. Trust

accumulates and dissipates based on the cumulative

interactions with the other agent. These interactions lead

to an accumulation of knowledge that establishes trust

through an expected value calculation, where the

probability of various outcomes is estimated with

increasing experience (Holmes, 1991).

Trust can also develop according to rules that link levels of

trust to characteristics of the agent. These can develop

through direct observation of the trusted agent,

intermediaries that convey their observations, and

presumptions based on standards, category membership,

and procedures (Kramer, 1999). Trust may depend on the

application of rules rather than on conscious calculations.

Explicit and implicit rules frequently guide individual and

collective collaborative behavior (Mishra, 1996). Sitkin

and Roth (1993) illustrate the importance of rules in their

distinction between trust as an institutional arrangement

and interpersonal trust. Institutional trust reflects the use

of contracts, legal procedures, and formal rules, whereas

interpersonal trust depends on shared values.

The

application of rules in institution-based trust reflects

guarantees and safety nets based on the organizational

constraints of regulations, guarantees, and legal recourse

that constrain behavior and make it more possible to trust

(McKnight, Cummings, & Chervany, 1998). Institutionbased trust increases people’s expectation of satisfactory

performance during times of normal operation by pairing

situations with rule-based expectations.

Intermediaries can also convey information to support

judgments of trust (Baba, 1999). Similarly, trust can be

based on presumptions of the trustworthiness of a category

or role of the agent rather than on the actual performance

of the agent (Kramer, 1999). If trust depends on rules that

characterize performance during normal situations, then

abnormal situations can lead trust to collapse because the

assurances associated with normal or customary operation

are no longer valid. Because of this, role and categorybased trust can be fragile, particularly when abnormal

situations disrupt otherwise stable roles.

Calculative and rule-based processes do not account for the

affective characteristics of trust, and fail to consider the

social and affective aspects of trust (Kramer, 1999).

Emotional responses are critical because people not only

think about trust, they also feel it (Fine & Holyfield, 1996).

Emotions fluctuate over time according to the performance

of the other agent, and they can signal instances where

expectations do not conform to the ongoing experience.

As trust is betrayed, emotions provide signals concerning

the changing nature of the situation (Jones & George,

1998).

Berscheid (1994) uses the concept of automatic processing

to describe how events that are relevant to affective trait

constructs, such as trust, are likely to be perceived even

under attentional overload situations. Because of this,

people process observations of new behavior according to

these constructs without always being aware of doing so.

Automatic processing plays a substantial role in

attributional activities, with many aspects of causal

reasoning occurring outside conscious awareness. In this

way, emotions bridge the gaps in rationality and enable

people to focus their limited attentional capacity (JohnsonLaird & Oately, 1992). Because the cognitive complexity

of relationships can exceed a person’s capacity to form a

complete mental model, people cannot perfectly predict

behavior, and emotions serve to redistribute cognitive

resources, manage priorities, and make decisions with

imperfect information (Johnson-Laird & Oately, 1992).

This is particularly critical when rules fail to apply and

when cognitive resources are not available to support a

calculated rational choice. The affective nature of trust

seems to parallel some of the features of skill-based

behavior, where an internalized dynamic world model

guides behavior without conscious intervention

(Rasmussen, 1983).

Recent neurological evidence parallels these findings,

indicating that emotions play an important role in decisionmaking. This research is important because it suggests a

neurologically-based description for how trust might

influence reliance. Damasio (1990) showed that although

people with brain lesions in the ventromedial sector of the

prefrontal cortices retain reasoning and other cognitive

abilities, their emotions and decision-making ability are

critically impaired. In a simple gambling decision-making

task, those with prefrontal lesions performed much worse

than a control group of normal people. Patients responded

to immediate prospects and failed to accommodate longterm consequences (Bechara, Damasio, Damasio, &

Anderson, 1994). In a subsequent study, normal subjects

showed a substantial response to a large loss, as measured

by skin conductance response (SCR), a physiological

measure of emotion, whereas patients did not (Bechara,

Damasio, Tranel, & Damasio, 1997). Interestingly, normal

subjects also demonstrated an anticipatory SCR and began

to avoid risky choices before they explicitly recognized the

alternative as being risky. These results strongly support

the argument that emotions play an important role in

decision-making, and that emotional reactions may

mediate trust without conscious awareness.

Emotion influences not only individual decision making

but also the decision making of groups, suggesting that

affect-based trust may play an important role in governing

reliance on automation. Emotion plays an important role

in decision making by supporting implicit communication

between several people (Pally, 1998). The tone, rhythm

and quality of speech convey information about the

emotional states of individuals, and so regulate the

physiological emotional responses of everyone involved.

People spontaneously match non-verbal cues to generate

emotional attunement. Emotional, non-verbal exchanges

are a critical complement to the analytic information in a

verbal exchange (Pally, 1998). These neuropsychological

results seem consistent with recent findings regarding

interpersonal trust in which anonymous computerized

messages were found to be not as effective as face-to-face

communication because individuals judge trustworthiness

from facial expressions and from hearing the way others

talk (Rocco, 1998). These results suggest that trust

calibration could be aided by incorporating a rich array of

informal cues into the computer interface. These cues

might begin to replicate the emotional attunement of faceto-face interactions between people.

Results from many studies show that develops and

influences behavior in more than one way. Trust between

individuals and in automation likely depends on a complex

interaction of knowledge-based calculations, rule-based

categorizations, and most importantly, the implicit skillbased interpretation of information.

The dynamic process of trust and reliance

Figure 1 shows that trust and its effect on reliance are part

of a closed-loop process, where the dynamic interaction

with the automation governs trust. If the system is not

trusted, it is unlikely to be used; if it is not used, the person

will have limited information regarding its capabilities and

it is unlikely that trust will grow. Because trust is largely

based on the observation of the automation, automation

must be relied upon for trust to grow (Muir & Moray,

1996). Relying on automation provides operators with an

opportunity to observe the automation and thus to develop

increasingly greater levels of trust.

The dynamic interplay between changes in trust, the effect

of these changes on reliance, and the resulting feedback

can generate substantial non-linear effects. The non-linear

cascade of effects noted in the dynamics of interpersonal

trust (Ostrom, 1997) and the high degree of volatility in the

level of trust in some relationships suggests a similar

phenomena occurs between people (McKnight et al.,

1998). This non-linear behavior may also account for the

large individual differences noted in human-automation

trust (Lee & Moray, 1994; Moray et al., 2000). A small

difference in the predisposition to trust may have a

substantial effect when it influences an initial decision to

engage the automation. A small difference in the initial

level of trust might, for example, lead one person to engage

the automation and another to adopt manual control.

Reliance on the automation may then lead to a substantial

increase in trust, whereas the trust of the person who

adopted manual control might decline. Characterizing the

dynamics of the feedback loop shown in Figure 1 is

essential to understanding why trust sometimes appears

volatile and other times stable.

This closed-loop

framework also highlights the importance of temporal

specificity in characterizing the appropriateness of trust.

The higher the temporal specificity, the more likely that

trust will correspond to the current capability of the

automaton. Poor temporal specificity will act as a time

delay, undermining system stability and increasing the

volatility of trust. The closed loop feedback may explain

how operator, environment, and automation characteristics

combine over time to affect trust and reliance.

Context and trust

Figure 1 shows that trust is an intervening variable that

indirectly influences intention and reliance.

Beliefs

combine with individual differences, such as the

predisposition to trust, to determine the level of trust in the

automation. Predisposition to trust is most important when

a situation is ambiguous and generalized expectancies

dominate, and becomes less important as the relationship

progresses (McKnight et al., 1998). The level of trust

combines with other attitudes and expectations such as

subjective workload and self-confidence to determine the

intention to rely on the automation. Self-confidence is

particularly critical factor in decision making in general

(Bandura, 1982; Gist & Mitchell, 1992) and in mediating

the effect of trust on reliance in particular (Lee & Moray,

1994). A variety of system and human performance

constraints affect how the intention to rely on automation

translates into actual reliance (Kirlik, 1993). For example,

the operator may intend to use the automation but not have

sufficient time to engage it. Understanding the role of trust

in the decision to rely on automation requires a

consideration of the operating context that goes beyond

trust alone.

The conceptual model in Figure 1 helps integrate the

research from psychology, sociology, and management

science. Most importantly, it shows that trust depends on

the dynamic interaction between operator, environment,

and automation characteristics.

Conclusions

A substantial research base from several disciplines

suggests that trust is an important mechanism to cope with

the increasing cognitive complexity associated with new

technology. In particular, research shows that trust

mediates reliance on automation. This review describes a

conceptual model of trust that can guide research and

design. Specific conclusions include:

•

•

Trust influences reliance as an attitude in the

context of beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and

behavior. Reliance is not a good measure of trust.

Designers should focus on calibrating trust not

necessarily enhancing trust. Maximizing trust is

often a poor design goal.

•

•

•

•

Trust depends on information assimilated through

calculative-, rule-, and skill-based processes.

Calibrating trust requires interface design that

considers qualitatively different cognitive

processes that influence trust.

Dynamic relationship between person and

automation

helps

explain

non-linear

characteristics of trust and reliance. Trust and

reliance may evolve over time in highly variable

and counterintuitive ways.

Interface design should capitalize on people’s

ability to process affective stimuli. Interface

design should incorporate subtle cues that guide

interpersonal responses, such as auditory cues

associated with verbal inflections, sighs, and

pauses to indicate uncertainty.

Systems that mimic human characteristics, may

inadvertently lead to inappropriate levels of trust

as the human characteristics lead to false

expectations. Human-like features should not be

arbitrarily incorporated into a design, but should

be carefully designed to calibrate trust.

These general points provide important considerations for

how systems might be designed and evaluated to enhance

trust calibration.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the NSF, IIS 0117494.

References

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes

and predicting social behavior. Upper Saddle

River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Baba, M. L. (1999). Dangerous liaisons: Trust, distrust,

and information technology in American work

organizations. Human Organization, 58(3), 331346.

Bandura. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human

agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S.

W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences

following damage to human prefrontal cortex.

Cognition, 50(1-3), 7-15.

Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Tranel, D., & Damasio, A. R.

(1997). Deciding advantageously before knowing

the advantageous strategy. Science, 275(5304),

1293-1295.

Berscheid, E. (1994). Interpersonal relationships. Annual

Review of Psychology, 45, 79-129.

Corritore, C. L., Kracher, B., & Wiedenbeck, S. (2001).

Trust in the online environment. Seattle, WA: CHI

workshop.

Damasio, A. R., Tranel, D., & Damasio, H. (1990).

Individuals with sociopathic behavior caused by

frontal damage fail to respond autonomically to

social-stimuli. Behavioural Brain Research,

41(2), 81-94.

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. Journal of

Conflict Resolution, 2(4), 265-279.

Deutsch, M. (1969). Trust and suspicion. Conflict

Resolution, III(4), 265-279.

Doney, P. M., Cannon, J. P., & Mullen, M. R. (1998).

Understanding the influence of national culture on

the development of trust. Academy of

Management Review, 23(3), 601-620.

Fine, G. A., & Holyfield, L. (1996). Secrecy, trust, and

dangerous leisure: Generating group cohesion in

voluntary organizations. Social Psychology

Quarterly., 59(1), 22-38.

Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude,

Intention, and Behavior. Reading, MA: AddisonWesley.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy - A

theoretical-analysis of its determinants and

malleability. Academy of Management Review,

17(2), 183-211.

Hardin, R. (1992). The street-level epistemology of trust.

Politics and Society, 21, 505-529.

Holmes, J. G. (1991). Trust and the appraisal process in

close relationships. In W. H. Jones & D. Perlman

(Eds.), Advances in Personal Relationships (Vol.

2, pp. 57-104). London: Jessica Kingsley.

Johnson-Laird, P. N., & Oately, K. (1992). Basic emotions,

rationality, and folk theory. Cognition and

Emotion, 6, 201-223.

Jones, G. R., & George, J. M. (1998). The experience and

evolution of trust: Implications for cooperation

and teamwork. Academy of Management Review,

23(3), 531-546.

Kirlik, A. (1993). Modeling strategic behavior in humanautomation interaction: Why an "aid" can (and

should go unused. Human Factors, 35(2), 221242.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations:

Emerging perspectives, enduring questions.

Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 569-598.

Kramer, R. M., & Tyler, T. R. (1996). Trust in

organizations: Frontiers of theory and research.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Lee, J., & Moray, N. (1992). Trust, control strategies and

allocation of function in human-machine systems.

Ergonomics, 35(10), 1243-1270.

Lee, J. D., & Moray, N. (1994). Trust, self-confidence, and

operators' adaptation to automation. International

Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 40, 153184.

Lee, J. D., & Sanquist, T. F. (2000). Augmenting the

operator function model with cognitive

operations: Assessing the cognitive demands of

technological innovation in ship navigation. IEEE

Transactions on Systems, Man, and CyberneticsPart A: Systems and Humans, 30(3), 273-285.

Lewandowsky, S., Mundy, M., & Tan, G. (2000). The

dynamics of trust: Comparing humans to

automation. Journal of Experimental PsychologyApplied, 6(2), 104-123.

Lewicki, R. J., & Bunker, B. B. (1996). Developing and

maintaining trust in work relationships. In R. M.

Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in

organizations: Frontiers of theory and research

(pp. 114-139). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publishers.

McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L.

(1998). Initial trust formation in new

organizational relationships. Academy of

Management Review, 23(3), 473-490.

Mishra, A. K. (1996). Organizational response to crisis. In

R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.),

Organizational trust: Frontiers of research and

theory (pp. 261-287). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publishers.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993).

Factors affecting trust in market-research

relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81101.

Moray, N., Inagaki, T., & Itoh, M. (2000). Adaptive

automation, trust, and self-confidence in fault

management of time-critical tasks. Journal of

Experimental Psychology-Applied, 6(1), 44-58.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitmenttrust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of

Marketing, 58(3), 20-38.

Muir, B. M., & Moray, N. (1996). Trust in automation 2:

Experimental studies of trust and human

intervention in a process control simulation.

Ergonomics, 39(3), 429-460.

Muller, G. (1996). Secure communication - Trust in

technology or trust with technology?

Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 21(4), 336347.

Nass, C., Moon, Y., Fogg, B. J., Reeves, B., & Dryer, D.

C. (1995). Can computer personalities be human

personalities? International Journal of HumanComputer Studies, 43, 223-239.

Norman, D. A., Ortony, A., & Russell, D. M. (in press).

Affect and machine design: Lessons for the

development of autonomous machines. IBM

Systems Journal.

Nyhan, R. C. (2000). Changing the paradigm - Trust and

its role in public sector organizations. American

Review of Public Administration, 30(1), 87-109.

Ostrom. (1997).

Ostrom, E. (1998). A behavioral approach to the rational

choice theory of collective action. American

Political Science Review, 92(1), 1-22.

Pally, R. (1998). Emotional processing: The mind-body

connection. International Journal of PsychoAnalysis, 79, 349-362.

Parasuraman, R., & Riley, V. (1997). Humans and

Automation: Use, misuse, disuse, abuse. Human

Factors, 39(2), 230-253.

Picard, R. W. (1997). Affective computing. Cambridge,

Mass.: MIT Press.

Rasmussen, J. (1983). Skills, rules, and knowledge:

Signals, signs, and symbols, and other distinctions

in human performance models. SMC-13(3), 257266.

Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The Media Equation: How

people treat computers, television, and new media

like real people and places. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Rempel, J. K., Holmes, J. G., & Zanna, M. P. (1985). Trust

in close relationships. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 49(1), 95-112.

Riley, V. (1989). A general model of mixed-initiative

human-machine systems. Paper presented at the

Proceedings of the Human Factors Society 33rd

Annual Meeting.

Ring, P. S., & Vandeven, A. H. (1992). Structuring

cooperative relationships between organizations.

Strategic Management Journal, 13(7), 483-498.

Rocco, E. (1998). Trust breaks down in electronic contexts

bu can be repaired by some initial face-to-face

contact. Proceedings on Human Factors in

Computing Systems, 496-502.

Ross, W., & LaCroix, J. (1996). Multiple meanings of trust

in negotiation theory and research: A literature

review and integrative model. International

Journal of Conflict Management, 7(4), 314-360.

Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of

interpersonal trust. Journal of Personality, 35(4),

651-665.

Sheridan, T. B., & Hennessy, R. T. (1984). Research and

modeling of supervisory control behavior.

Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Sitkin, S. B., & Roth, N. L. (1993). Explaining the limited

effectiveness of legalistic remedies for trust

distrust. Organization Science, 4(3), 367-392.

Sparaco, P. (1995). Airbus seeks to keep pilot, new

technology in harmony. Aviation Week and Space

Technology, January 30, 62-63.

Tan, H. H., & Tan, C. S. (2000). Toward the differentiation

of trust in supervisor and trust in organization.

Genetic, Social, and General Psychological

Monographs, 126(2), 241-260.

Tseng, S., & Fogg, B. J. (1999). Credibility and computing

technology. Communications of the ACM, 42(5),

39-44.

Williamson, O. (1993). Calculativeness, trust and

economic-organization. Journal of Law and

Economics, 36(1), 453-486.

Zuboff, S. (1988). In the age of smart machines: The future

of work technology and power. New York: Basic

Books.