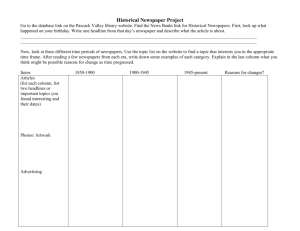

Historical Insights

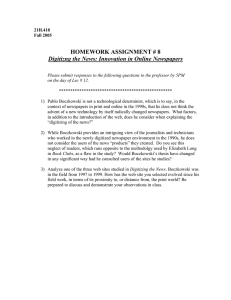

advertisement