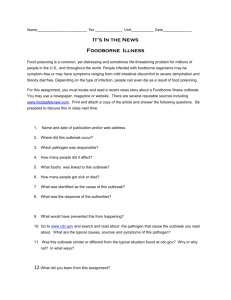

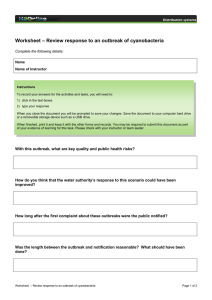

Guidelines for foodborne disease outbreak response

advertisement