From: AAAI Technical Report SS-94-07. Compilation copyright © 1994, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Modeling Organizations:

Methods Used by Real-world

Designers

Submission to the AAAI-94Spring Symposiumon

ComputationOrganization Design

Bryan Borys

ComputationalOrganizational Design Lab

Institute for Safety and SystemManagement

University of SouthemCalifornia

Los Angeles, CA90089-0021

213/740-4045

borys@usc.edu

Formal,abstract computationaltechniques for modelingorganizations imply certain approachesto

certain modelingproblems. Less formal techniques used by people involved in concrete design

contexts in real organizations(real-world designers)face the sameproblems,but use different

approaches.Foursuch problemsare considered: the problemsof simplification (whichfeatures to

model, whichto ignore), granularity (what unit of analysis to adopt), simulation(howto verify

accuracyand consistency of the model), and agency(howto be certain that the agents modeledwill

respondto certain signals in certain ways). Approachesof computationalorganization design

(COD)and real-world design (RWD)to each of these problems are comparedand somelessons

both CODand RWDare drawn.

Introduction

hope that further refinementswill yield more

faithful models.

Analogousproblems face designers of

organizations in "real-world" settings)

Practitioners of real-world design (RWD)must

also transform their chaotic, ambiguousand

confusing observations of organizational

2behavior into a format amenableto design.

Central problemsof computationorganization

design (COD)result from the gap between,

one hand, "natural" representations of

organizations that are meaningfulto

organizational members,and on the other hand

the formal representations required by available

computational techniques. CODproceeds by

makingsimplifying assumptions about

organizations which makecomputationeasier.

COD

modelerssacrifice faithfulness to reality in

the nameof modelingexpediency, often with the

1 I use quotes aroundthe term "real-world" (in this

instance only) in recognition of the fact that the

distinction betweenreal-world design and COD

is one of

degree: "real-world" designers use formal techniquesjust as

do those involved in creating or using COD

systems.

2 For detailed discussions of this problem,see Bryan

Borys, Where Do Rules ComeFrom?: ParticipantObservationof the Process of Administrative Innovation,

unpublisheddoctoral dissertation, GraduateSchoolof

11

p. 2

Nonetheless, the activities

of real-world

by its explicit requirements -- they are thus more

designers are more deeply embeddedin a

vulnerable to bias than the CODpractitioner

particular organizational context than that of COD

pursuing abstract models.

practitioners.

The task of CODis to generate an

For re’d-world designers, bridging the gap

abstract representation of organizational behavior

between organizations

amenable to simulation, generation of design

organizations involves applying two things:

alternatives,

First, their native understandings of the

etc. The task of RWD

is to generate

and models of

a concrete, workable design that will address

organization they are attempting to (re)design.

specific problemsin a specific organization.

Second, the everyday methods they use to

In pursing RWD,designers have access to,

managethe rich complexity of everyday life.

The

and are influenced by, a rich set of organization-

approaches they use for bridging the gap and

specific knowledge(e.g., culture, standard

managing the problems of organizational

practice, knowledgeof individual

modeling provide a fruitful

idiosyncrasies).

formal and abstract approaches developed in the

Whatmight be considered

extraneous issues from a CODperspective are

counterpoint to more

CODliterature.

kept at the forefront of the RWD

task. For

Real-world

instance, some real-world designers tend to

Central

ignore certain organizational features that might

problems

design:

and approaches

embarrass or offend) Thus real-world design is

more deeply embedded in the rich, complex and

Whatfollows is a set of observations of a

often unprogrammableworld that sociologists

group of real-world organization designers.

with a penchant for neologism call "everyday

These designers were members of a formal

life."

process improvementteam at a large electronics

manufacturer I shall call "Electra. ’’4 The Electra

This embeddedness has two implications that

differentiate

RWDfrom COD:First,

design team was charged with using basic

since RWD

is embeddedin an organizational context, real-

"business process reengineering" methods5 to

world designers have access to knowledge that

improve the speed of Electra’s engineering

helps them get around tricky modeling

change process. The most difficult

problems-- they thus have a leg up on the more

task was to map the existing engineering change

abstract and formalistic

process; this step took up about two-thirds of the

CODdesigners. Second,

part of this

design team’s time.

however, this same access sometimes leads realworld designers to generate models that are more

I shall highlight some of the major problems

influenced by the context of the design task than

that faced these real-world designers and identify

Business,StanfordUniversity,1992;and"’Seeingthe

Elephant’: A GroundedTheoryof the Role of Knowledge

Interests in BusinessProcessReengineering,"unpublished

manuscript, submittedto the 1994Academy

of

Management

meetings.

3 See Borys,1992,op cit.

4 Moredetaileddescriptionsandanalysesof the Electra

case can be foundin Borys,1992,op cit.

5 See, for instance, Hammer,

Michaeland Champy,

James. 1993. Reengineeringthe Corporation:A

Manifestofor Business Revolution, NewYork:

HarperBusiness.

12

p. 3

howthe designers approachedthe problems.

problemsor problemswhosesolutions lie

6beyondthe capacities of the designers.

Thusthe implementationcontext (rather than

merely the available evidenceand modelingtools)

influences howthe modelis simplified. One

result is that real-worlddesigns tend to more

readily implementablethan CODdesigns,

becauseimplementationissues are (often

surreptitiously) importedinto the modeling

process. Theother side of this coin, however,is

that RWD

maymerely replicate existing

organizational problems, where moreformal and

abstract CODtechniques force designers to

address them.

This suggests that design-forimplementability(DFI) is an important

consideration: CODdesigns, generated by a COD

expert far from actual organizations, mayignore

crucial factors that impedethe utility of the

resulting design. It also highlights, however,the

danger that DFImayserve merely to legitimize

the glossing of importantorganizational

problems.

Fromthis discussion I shall drawsomelessons,

or at least somecautions, for those workingin

COD.

1) Theproblemof simplification.

All models simplify. CODmodels often

simplify on the basis of computationalease,

makingassumptionsthat are necessary to allow

the use of available methodsand representations.

Real-worlddesigners simplify, as well. The

representationaltools available to real-world

designerscan be quite rich: flowcharts,

diagrams, organization charts and prose

descriptions of activities can conveya richness of

meaningand a level of complexitythat is

infeasible for moreformalrepresentations.

Nonetheless, these tools imposelimits on

complexity, as well. Thusreal-world designers

’also face the problemof whenand howto

simplify, to gloss, to ignore.

Thequalitative difference betweenreal-world

design and COD

is that real-world designers

often simplify on the basis of "practical"

demands-- their simplifications facilitate

successful action in a specific organizational

context, not merely successful computationor

accurate representation. Real-worlddesigns are

often evaluatedin termsof their implicationsfor

action -- evento the point where

implementabilityis a greater concernthan

accuracyin representation. For instance,

designers tend to modelfeatures that create

important and fixable problemsand ignore

modelablefeatures that generate unimportant

2) The problemof granularity.

In modelingbehavioral processes, an

importantissue is to choosethe appropriateunit

of analysis -- that is, should wemodel

behaviors, tasks, inputs/outputs, "steps" in a

process, etc.? CODmodelstypically adopt some

stylized unit (e.g., "transaction")that is hardcodedinto the formal representational scheme.

CODdesigns thus tend to consistently implement

a particular choice of granularity throughoutthe

model.

6 See Borys, 1992, op cit.

13

p. 4

an outsider could not comprehend

it in greater

detail. Such"black boxing"of certain areas

protects them from outsiders’ meddling.

It also, however,influences the granularity of

real-world designers’ models. Thusthe choice of

howfine-grained a modelshould be is

influenced, for real-world designers, as muchby

language, organizational structure, and

organizationalpolitics as by the formal

requirements of the modelingenvironment.

Again we find a two-sided result: RWD

sacrifices

consistent implementationand is moreopen to

bias than moreformal methods.But on the other

hand it moreeasily captures modelsof task

structures that are moreinherently meaningful

than some CODontologies.

For real-world designers, determiningthe

appropriategranularity is a constant problem.

Whatis appropriate is determinedin part by more

or less "natural" chunksof activities. Thelevel of

granularity maydiffer across parts of the

organization that is being modeled.For instance,

activities within a Financefunction are often

governedby quite explicit rules governingquite

"small" tasks. Theseprovide a languagefor

renderingFinance-relatedactivities in a finegrained way;this languageis adoptableby realworld designers. The language of Design

Engineering,by contrast, is full of "black

boxes," in whichmanyactivities are implied, but

not analyzed(e.g., "generate design

alternatives"). Thusreadily available modelsof

DesignEngineeringtend to be coarser-grained

than those of Finance. A task in Finance may

take one personseveral minutes; yet a task in

Design Engineeringmaytake several people

several months. Thelanguage of tasks in Finance

3) The problemof simulation.

Amajorbenefit of COD

is that it facilitates

simulationof various organizational features.

Such simulation allows the CODmodeler to

generatea result, compareit to empiricalresults,

and thus verify the accuracy and consistency of

and in DesignEngineeringfacilitate modelingat

quite different levels of detail.

Organizationalpolitics seemto play a role in

such distinctions. Givenreadily available models

of DesignEngineering,it is nonetheless possible

to delve into the design task in moredetail (e.g.,

by asking "Howdo you generate design

alternatives?"). Designengineers are often

resistant to such probing, however.Their

defenseis that their workis not amenableto such

fine-grainedanalysis. As I tried to uncoverthe

fmedetail of a particular design engineering

decision, for instance, twoengineersin separate

conversations gave the sameresponse: They

couldnot explain the steps involvedin that

particular process; all they couldsay wasthat

"it’s an engineeringdecision." Theyimpliedthat

the model.

For real-world designers, simulation and

consistency-checkingis both morerich and less

systematic and accurate. Since real-world designs

are typically lists of features or steps in a paper

flow chart, real-world designers must supply

their ownmediumof simulation and test. The

most natural and perhaps the most pervasive is

the narrative: real-world designers "talk through"

the implications of their models,checking

whether the models "makesense."

Theproblemfor real-world design is that

forcing modelsto "makesense" in the context

adopted by the real-world design group may

introduce spurious elements. "Narrative

14

p. 5

simulation and checkingincreases the intemal

simulation’’ forces the elementsof the modelinto

a specific context in whichthey maynot make

sense. Re’d-worlddesigners thus maysacrifice

accuracy for meaningfulness.

Oneby-productof narrative simulation is

"filling in the gaps": a frequentsourceof

spurious information. Narratives encouragethe

narrator to introduce his or her ownknowledge

in the place of informationthat missingfromthe

story. For instance, Elecu’adesignersoften filled

in the wholesin informants’accounts of the

engineering changeprocess. Oncethey had

mappedseveral pieces of the process, they talked

through an exampleengineering change. At

several points they found gaps in the model.The

typically response wasto say "what they must

meanis..." and to fill that gap with their own

(often wrong) knowledge.

Anotherby-productis that elementsthat

appear logically inconsistent are often removedor

glossed, rather than acceptedas evidenceof the

designers’ lack of understanding.7 Narratives

makesense only within a particular context. For

instance, simulating the engineering change

process modelby imaginingthe history of an

engineering changerequiring a changeto a

printed circuit board layout mightgenerate

different issues than a narrative history of a

consistency from a very formal standpoint. For

real-world design, the process often cannot

providethe samelevel of rigor. Instead,

however,real-world design simulation increases

the meaningfulnessand credibility of the model.

4) The problemof action.

A popular COD

conventionis to treat actors

as "agents" that respondto certain (predefined)

communicationswith certain (predefined)

routines. Asignal to an agent triggers a specific

response(or set of responses;or triggers it with

certain probability).

In contrast to this sanguineassumption,

RWD

takes the "agency problem"as a central

issue. Thetacit assumptionunderlying the design

of mostorganizationalstructures is that clear

communications,coupled with clear and certain

rewards and punishments,are sufficient to

ensure appropriate behaviors. To assume

otherwise is to becomequite pessimistic about

the possibility of coordinatingthe behaviorof

large numbersof people without tremendouscost

(e.g., in face-to-face meetings). Nonetheless,

everydayoccurrencescontinually challenge this

assumption. People issue orders and requests

that generate unexpectedresponses becausethe

personreceivingthe signal interprets it differently

than the sender intended. Such communications

are moreor less deeply context-dependent;thus

real-worlddesigners try to incorporatetheir

native understandingsof signalling contexts into

their designs.

For real-world designers, the problemis:

Howcan they be confident that a given signal

will result in certain actions? Real-world

designers havea rich set of schemasof agent

fictitious changeinvolvinga newelectronic

component.

Theresult is that simulationin real-world

design, insofar as it relies on placinga particular

modelwithin a specific context, limits the

robustnessof the simulation. Theflip side of this

is that, again, the end result is a modelthat has

greater a priori meaningfulness. For COD,

7 ibid.

15

p. 6

literature: for instance, that DesignEngineersare

often not receptive to signals fromManufacturing

about the "manufacturability"of their designs.)

Thereceiver’s resources, skills, etc. A

seconddimensionis the receiver’s capacity for

respondingto the trigger. For those likely to act,

but in unpredictable ways, signals must include

directions for action. TheElectra design team

distinguished between"process" problems,

responsivenessand signalling contexts. These

schemashelp them analyze typical contexts and

decide on whichtypes of signals are better or

worsetriggers of which types of behavior. These

schemasaddress: first, the motivationsof

particular receivers; second,the resources of the

receiver; and third, the nature of the signal. The

schemashelp real-world designers approachthe

agencyproblemwith a rich repertoire of

solutions.

Thereceiver’s motivation, Oneaspect of the

which stemmedfrom lack of triggers, and

"training" problems,causedby a lack of

understandingof howto respond to a trigger. A

Draftsperson, for instance, maybe able to

respondadequatelyto a request for a revised set

of paperdrawings,but maynot be able to fulfill a

request for the sameset of drawingsto be set

signalling context is a presumptionof the

receiver’s willingness to conformto the sender’s

intent. Someactors are knownfor their

"initiative" and thus can be expectedto take

action given only information, rather than

specific directions. At the other end of the

initiative spectrumare agents whohavea

over electronic mail.

Thenature of the signal. In addition to the

propensityand ability of the receiver to conform

to the signal, anotheraspect of the signaling

context is the nature of the signal. Oneway

Electra designers conceivedof the force of the

signal wasin terms of the "hardness"of the

information conveyed. "Hard information" was

unambiguousand final -- and which, for that

reason, waspresumablyan effective stimulus of

a particular behavior. Soft information,on the

other hand, was knownby both parties to be

ambiguousand subject to change and thus more

likely to allow for multipleinterpretations and

multiple responses.

propensity to shirk from certain tasks. For such

agents, simply conveyinginformation is not

enough;for those whoare likely to not act,

formal orders must be providedin addition to

information.

Anticipatingthe interpretation of a particular

signal-to-act thus involvesinferring the likely

state of the receiving agent. Thereare no general

rules for addressingthis issue; real-world

designers’ backgroundknowledgeabout the

organization provides the basis for such

inferences. For instance, according to a member

of the Electra organizationdesign team, "Drafting

won’t do anything without a WorkOrder." Such

a statement, necessaryto specify the proper

signal, is specific to Electra. Thereis no general

statement about the relationship betweenDesign

Engineering demands,Drafting responses and

workorders outside Electra. (Althoughslightly

moregeneral hypothesesmaybe available in the

Theproblemis that hardness is contextual. At

another organization, for instance, design

engineers gave preliminarycost estimates to sales

personnelso the latter couldplan their sales

strategy. Oncethey had the information,

however, somesales managersbeganusing it to

quote prices for customers,thus locking the

16

companyinto those estimates. Whatseemedlike

"soft," "guesswork"cost information to the

engineer wasinterpreted as a formally binding

cost estimate by a sales manager.

The problemis that one cannot always

foresee the context in whichinformationwill be

interpreted. Thus real-world designers sometimes

create an artificial contextby formallylabeling

information. Electra organization designers used

formal proceduresto bind a particular predefined

interpretation to a particular predefinedcontext.

For instance, cost information was formally and

explicitly labeled "hard" and "soft" accordingto

the particular task whichgeneratedit. Further,

real-world designers mayattempt to manipulate

the hardnessof the informationis specific

contexts. "I’d like to firm up that info," said Jim,

a memberof the Electra team, as he proposeda

rule that requireda particular report to be

interpreted as a final cost estimate, rather than

"soft, waffieystuff." Suchrules not only tells the

receiver howto interpret the cost data. Theyalso

encouragesthe sender to be morecareful about

howtheir signal mightbe received.

Often, however,real-world designers cannot

completelyand confidently specify the nature of a

signal. Theythus resort to markersfor such

ambiguity.For instance, "Designtells Drafting to

makechangesto drawings," reads the Electra

design; the designers could give no morespecific

advice about howto tell Draftingto do so.

Signals are invariablycontext-specific. In the

CODparadigm, receivers’ motivations and

capacities are modeledand certain specific signals

are assumedto havecertain efficacy. Thusthe

CODparadigmassumesa particular context. For

real-world designers, such issues are subject to

p. 7

continual revision, based on organization-specific

knowledge.Real-world designers recognize that

contexts shift. Theyrespondto such uncertainty

by bindingspecifiable contexts to particular

signals; but such a strategy can only be partially

effective.

Conclusions

Real-worlddesigners do not necessarily use

better strategies for solving problemsof

organizationalrepresentation. Neither are all of

their strategies available for researchers working

in COD.But by describing, typifying and

understandingreal-world design in natural

settings, wemight find someuseful extensions to

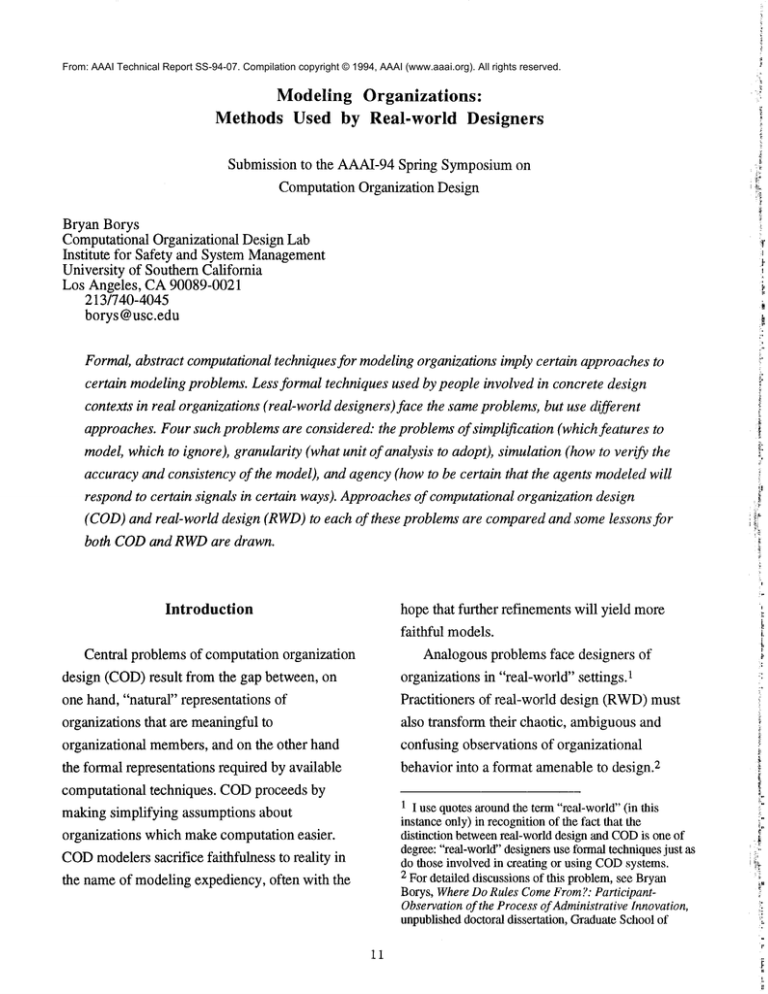

COD.The basic contrast between RWDand

CODapproaches, as suggested by Table 1

below, is that RWD

trades rigor for riclmess and

meaningfulness.

Both CODand RWDprovide screens for

deciding what features to modeland whichto

ignore. COD

often proceeds by ignoring features

that cannot be modeledwith available modeling

techniques. RWD

often proceeds by ignoring

features that raise political problems,that violate

organizationalnorms,or that raise issues that are

not solvable by designers.

Both CODand RWD

must choose a level of

analysis, a level of granularity. For COD,this

choice is typically embodiedin an ontologythat

is then consistently implementedthroughoutthe

model. For RWD,

granularity is a function of the

natural-languageontologies of organizational

members.It thus is moreinherently meaningful,

but also shifts fromarea to area.

Both CODand RWD

have provisions for

simulating and testing their models. COD

17

p. 8

simulation techniquesare quite rigorous

comparedto RWD

techniques, which often rely

on the vagaries of narrative simulation.

Nonetheless,nan’ative simulationis a better

guarantor that the model"makessense" in a

specific organizationalcontext.

Both CODand RWDmust address the

agencyproblem, or the question of howthe

agents they modelwill respondto the signals

they are provided. Thesignal-response set is

dependentuponthe context in whichthe signal is

sent and received. CODdesigners assumea

particular type of signal context. RWD

designers,

by contrast, haverich schemasof signal contexts

they employto analyzevarious contexts in detail;

they attempt to use these schemasto bind certain

contextualfeatures to the signal, with moreor

less success.

As are most formal techniques, CODis

susceptibleto the criticism that gains to rigor

comeat the cost of a lost of meaningfulness.The

contrast with RWD

approaches amplifies such a

criticism. It also, however,highlights someof

the costs to meaningfulness:inconsistency, bias,

and reification of organizationalculture.

Understandingthe sources of these costs may

help us to makeCODmore meaningful without

suffering the samepitfalls.

18

p. 9

Table

1:

Comparisons

between

COD and

organizational

Problem

Simplification

RWD approaches

to

problems

of

modeling

Question

CODapproach

Whatto include?

four

RWDapproach

Excludes what cannot be

Excludesissues that raise

modeledby existing

political problems.

technique.

Granularity

Simulation

Agency

What’sthe level/unit of

Consistent throughout the

Uses natural taxonomies of

analysis?

model.

activities.

Howcan we check the

Context-independent,

Context-sensitive testing of

accuracy and consistency of

rigorous testing of many

features amenableto

our model?

aspects simultaneous.

narration.

Howcan be certain that the

Assumesa particular

Uses rich knowledgeof

agents in our modelbehavior signalling context.

aspects of signalling context

as we assumethey will?

to bindparticular features to

particular signals.

19