Document 13737510

advertisement

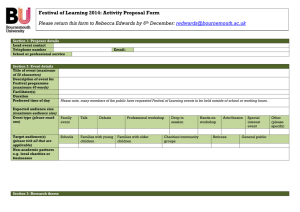

Festival-­‐based Public Engagement Dr Eric Jensen Assistant Professor of Sociology University of Warwick e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk 1 Seminar Overview Today we will discuss… • Key characteris-cs of fes-vals • Student volunteering in fes-vals • Fes-val Evalua-on – Feedback and Self-­‐report – Cambridge Science Fes-val Evalua-on example – Evalua-on Design – Survey Design 3 Ques'ons for you! 1. How would you define ‘public engagement’? (one sentence) 2. How would you define a ‘fes-val’? (one sentence) 3. If you went to a public engagement fes-val run by a university as a visitor, what would you be expec-ng from the experience? (one sentence) Speaker Background • Lecturing on research methods, MSc in Science, Media & Public Policy at Warwick. • Research on public engagement practice, impacts (e.g. festivals, London Zoo, Natural History Museum, etc.) • ISOTOPE project (Informing Science Outreach & Public Engagement) Informing Science Outreach and Public Engagement Informing science engagement prac-ce through theory and research • NESTA-­‐funded ac-on research project (2006-­‐2009) • Prac--oner-­‐led, academically edited website with informa-onal resources. ISOTOPE website (isotope.open.ac.uk) Introducing public engagement • ‘Public engagement’ can be seen as an umbrella term within which ‘public communica-on’, ‘public consulta-on’ and ‘public par-cipa-on’ all fall (Rowe & Frewer, 2005). • However, Rowe and Frewer (2000, p. 254) dis-nguish between – public par-cipa-on exercises, where “informa-on of some sort flows from the public to the exercise sponsors”, – communica-on exercises, where informa-on flows “solely from ‘sponsors’ to the public” OVER TO YOU! • What do you see as the defining characteris-c of a ‘Fes-val’ for public engagement? • What do you see as the inherent challenges and promise of Fes-val-­‐based Public Engagement? Discuss in groups of about 3 using your preliminary defini7ons as a point of discussion. Introducing Fes'val-­‐based public engagement • At one level, fes-vals are events, with many typical prac-cal tasks that have to be worked out, including – Venue selec-on – Health and safety management – Educa-onal content: for young people – Educa-onal content: for adults. – Event formats: programming talks, panel discussions, hands-­‐on ac-vity and other events – Use of online media to promote and enhance fes-vals – Design and branding for fes-vals – Ticke-ng and public informa-on for fes-val visitors Introducing Fes'val-­‐based public engagement • educa-onal fes-vals as enjoyment-­‐oriented sites for engaging publics with new ideas, knowledge and research. • Fes-vals defined by temporary / transient nature. – This transience has both posi-ve and nega-ve aspects. The Issue of Transience • Positive: – investment may be made in a level of activity which would be hard to sustain for a longer period. – People willing to try new things and encounter new ideas. • Negative: – Challenge of making a lasting impact. • Can address by linking into year-­‐round institutions and activities, which can embed the gains from the festival. University Student Volunteers and Festival-­‐based Public Engagement: Research Results Dr Eric Jensen Assistant Professor of Sociology University of Warwick e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk 12 Research Results: Overview • Student volunteers survey: – Fes-vals seen as posi-ve experience by vast majority of student volunteers – Perceived as valuable for skills development • Fes'val organisers survey: – Student volunteers fulfil crucial roles in spaces between paid staff’s capabili-es and responsibili-es – Enthusiasm enhances experience for both organisers and visi-ng publics Student Sample Table 1: Student Survey Sample Distribution by Festival Type Festival Type Percent Science, technology or nature (e.g. Cheltenham Science Festival) 69% Performing arts (e.g. Edinburgh Festival Fringe), or other music, theatre, dance etc. festival 28% Children’s / family (e.g. Belfast Children’s Festival) 5% Visual arts (e.g. Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art) 1% Film (e.g. Encounters Film Festival, Bristol) 1% Literary / books (e.g. Hay Festival) Other -­‐ 6% Note: Total percentage exceeds 100% because respondents could select multiple categories. Organiser Sample Table 1: Organiser Survey Sample Distribution by Festival Type Festival Type Percent Performing arts (e.g. Edinburgh Festival Fringe), or other music, theatre, dance etc. festival 61.7% Science, technology or nature (e.g. Cheltenham Science Festival) 42.6% Children’s / family (e.g. Belfast Children’s Festival) 36.2% Visual arts (e.g. Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art) Literary / books (e.g. Hay Festival) Film (e.g. Encounters Film Festival, Bristol) Other 34% 23.4% 17% 12.8% Note: Total percentage exceeds 100% because respondents could select multiple categories. Student Volunteers: Recruitment • University communica-on networks are key hub for recrui-ng student workers and volunteers – e.g. through e-­‐ mail lists or student socie-es. – Word of mouth (friends Student Volunteers Survey • Student volunteer respondents highly suppor-ve of fes-val-­‐based public engagement: – 92% would volunteer in future Student Volunteers Survey • Majority (75%) believe fes-val volunteering will help them in their future study or career (12% did not). Student Volunteers Survey: Motivations • Students interested in volunteering for: – “Skills / career development”; furthering their experience and future career possibili-es. – ‘Public engagement’ goals of engaging publics with their favoured subjects. Mo'va'ons: Example Quota'on “To be useful in science you need to be able to communicate your topic effec-vely and to all age ranges with all educa-onal backgrounds. When the opportunity to volunteer at the science fes-val came up I thought it would be a great opportunity to work at my communica-on skills and also experience public engagement first hand”. (F, Postgraduate, Russell Group) Student Volunteers Survey • Most common type of role (47%) was ‘educa-onal’, followed by ‘workshop or ac-vity leader’ (28%) and ‘steward’ (26%) . Student Volunteers Survey • 51% of respondents interacted with 1-­‐99 fes-val aiendees, 14% reported interac-ng with 100-­‐499 aiendees, about 10% with 500+ fes-val visitors. • 25% reported having no contact with fes-val visitors at all. • Interac-ng with visitors was iden-fied as a source of sa-sfac-on for student volunteers • Therefore, organisers should consider arranging for volunteers to spend -me interac-ng with visitors. Student Volunteers Survey • Student volunteers felt they made a “small contribu-on” individually, but were an important part of the fes-val’s “overall effec-veness”. Student Volunteers: Example Quota'on “Volunteers at the fes-val where I worked proved to be the face of the fes-val, as they are present at every single event as the front line of staff represen-ng the organisa-on. The volunteers had to do work that other staff members would not have had -me to do, but if those tasks had been neglected, the fes-val would not have been half as successful”. (F, Postgraduate, post-­‐1992) Student Volunteers Survey • Respondents highlighted importance of good training and guidance from fes-vals. • Good training and guidance is crucial: – to ensure volunteers’ effec-veness – to ensure volunteers have sa-sfactory experience that builds new skills they can take forward into employment and other sekngs. • Need for training to expand as few respondents had received detailed prac-cal training or guidance for their fes-val roles. Festival Organisers Survey • Fes-val organisers rely on having at least some paid staff, however majority of respondents employ five or fewer people. Festival Organisers Survey • While majority of organisers in sample work with universi-es (66%), a substan-al minority do not. • Given benefits of working with universi-es (and their students), these fes-vals should be a key focus for building new links Festival Organisers Survey • Festival organisers reported that the enthusiasm and expertise of volunteering students and staff comprised the most valuable aspect of engaging with universities in delivering their festivals. Festival Organisers Survey • Aligning with the results of the student survey, organisers overwhelmingly emphasised that the value of festival-­‐based volunteering for students centred on what could be categorized as “skills development/ employability”, as well as for expanding students’ range of professional contacts. Festival Organisers Survey • Fes-val organisers indicated that universi-es provide a great deal of support for fes-vals overall • Most olen universi-es by providing human resources in the form of unpaid student volunteers (70%) or speakers, ar-sts and workshop leaders (61%). • Universi-es are also more likely to offer fes-vals free venues (57%) than venues for hire (48%). Festival Organisers Survey • Least successful aspect of using student volunteers in festivals is high level of training required for each iteration of the festival. • Several festival organisers have had to adjust their expectations of student volunteers’ prior practical knowledge, starting training at a basic level. OVER TO YOU! • What do you think is reasonable to expect of university student volunteers and fes-val organisers in the social exchange of fes-val volunteering? Discuss in groups of about 3. University Student Volunteers and Festival-­‐based Public Engagement: Research Results Dr Eric Jensen Assistant Professor of Sociology University of Warwick e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk 33 FESTIVAL EVALUATION 34 2 Ques'ons for you! 1. How would you define ‘impact’ in context of fes-val-­‐based public engagement? (one sentence) 2. What should an ‘evalua-on’ be achieving in the context of fes-val-­‐based public engagement? (one sentence) Tricky Issues in Festival Evaluation • Educa-onal fes-vals typically encompass a wide range of different kinds of engagement ac-vi-es from which individual members of the public may select or encounter. • This variegated context raises a number of methodological challenges for evalua-on. Defining Impact • I define impact in terms questions like: – What difference have you made in people’s lives? – What ideas, relationships, interests, motivations have been transformed as a result of your intervention? (and in what ways?) Defining Impact • OR: ‘impact’ is the difference between the profile of those you engaged pre-intervention and their profile post-intervention. • That is, the overall net effects or results of an activity or intervention (intended or unintended). – i.e. what were those engaged like before you encountered them and what (if anything) changed for them as a result of your encounter? • Note that changes or ‘impacts’ can be in negative or dysfunctional directions! Defining Impact • Impacts could include: – development in learning – attitude and behaviour change – a greater sense of self-efficacy – enhanced curiosity or interest in a subject – improved skills – greater connectedness with others – improved understanding of self and the broader world / universe – improved confidence or skills, etc. Defining Impact Evaluation • The systematic collection and/ or analysis of information to provide useful and focused feedback on the effects of an activity or intervention. Why Evaluate? • To build a better understanding of your public, (e.g. needs, interests, motivations, language). • To inform your plans and to predict which engagement or learning methods and content will be most effective. • To know whether you have achieved your objectives (and why or why not). • To re-design your approach to be even more effective in future. Tricky Issues in Festival Evaluation Challenges include: 1. collec-ng data from a transitory visitor popula-on in a crowded informal context. 2. designing survey ques-ons that can accommodate feedback on a broad range of public engagement ac-vi-es 3. using untrained individuals working with diverse organisa-ons to collect data 4. analyzing the diversity of feedback on such mul--­‐faceted experiences in a way that allows common paierns to emerge. Tricky Issues in Festival Evaluation • Accurate Overall ARendance Counts: – Using representa-ve sampling can address this. – Using results from survey-­‐based evalua-on can help • E.g. You might have hard aiendance counts at all sit down events during the fes-val. • Survey can ask how many total sit down events people aiended. Dividing total hard count by the mean number of events aiended yields unique visitor result. • Gathering representa've feedback: – Can’t use comment cards as self-­‐selec-ng (non-­‐ representa-ve sample) – Can use brief data collec-on on site, collec-ng email address to send follow-­‐up online form. Festival Evaluation: Feedback and Self-Report Context • Although science festivals are becoming more prevalent, their impacts are underresearched, with very little quality research literature currently in print. – This study aimed to address this issue using rigorous social scientific methods – Results submitted for publication in a peer reviewed journal Methods • A combination of research methods was employed in this evaluation 1. Focus groups were conducted with attendees to investigate qualitative dimensions of impact on science festival attendees. 2. An on-site questionnaire (n = 957) – this short one-page questionnaire sought basic information about the demographic characteristics of CSF attendees, as well as their comments and ratings of festival events. • Comments about the festival were categorized and tallied to reveal patterns. Results: Questionnaire • Overall levels of satisfaction were heavily skewed towards the ‘Excellent’ end of the scale. With ‘1’ as ‘Poor’ and ‘5’ as ‘Excellent’, the mean rating was 4.53. Results: Questionnaire Table 3 – Generic positive and negative responses Code Number Positive 156 Negative 6 Results: Questionnaire Table 4 – Festival Impacts Code Number Creating Interest 230 Knowledge 125 Interactivity 23 Results: Questionnaire Table 5 – Festival Delivery Code Number Positive 181 Negative 28 Results: Ques'onnaire Event Sa-sfac-on Sta-s-cs • Statistically significant differences in satisfaction ratings were found based on the variable of ‘gender’, with female respondents significantly more satisfied with festival events than male respondents. • However, both male and female ratings skewed heavily towards ‘excellent’ (5 on the Likert scale) • Means of 4.47 and 4.58 respectively on 1-5 scale. • ‘Age’ was also found to be a significant predictor of Cambridge Science Festival satisfaction ratings (F(6, 696) = 2.62, p <.05). Mean scores were highest with the 41-50 year-old age category. Results: Focus Groups • Focus group results highlighted the processes of planning and selecting flows through Cambridge Science Festival • Perceived benefits of ‘live’ as compared to mediated science communication. • Social appropriation of festival visits. • Other issues related to science popularisation and the perceived failures of formal education were also raised. Conclusions: Cambridge Science Festival prior research • This evaluation research study has pointed to a number of important impacts fostered by the Cambridge Science Festival. • Some of the complexities of the ways in which festival attendees approach this informal engagement context can be seen in the focus group results, available in the full report. Cambridge Science Festival 2011 Evaluation Approach • On-site survey form distributed, collected by organisers and volunteer staff • Follow-up web survey to collect more detailed individual views • Focus group Evaluation Data Collection • Saturation sampling approach (gather data from as many people as possible: try not to discriminate). • Focus on people in queues, waiting for lecture to start, etc.). • Welcome to have a read for yourself when you collect them up. Please supply your data to the festival as a whole though for larger-scale analysis. Evaluation Data Collection • Invite visitors to contribute their feedback. State that we are very interested to learn what they think and we carefully analyse responses to improve the festival each year. • Discourage joint completion of evaluation forms. (These are designed for individuals to complete). • If they ask, say the evaluation report will be published on the CSF website a few months after the festival On-site evaluation form: p.1 (pt.2) Thank you for your help – your feedback will help us to improve and develop the Festival. Your anonymous responses about the festival will be used for evaluation and research purposes only. 1. Which event have you just attended? ___________________________ Date___________ 2. What was your impression of the event you just attended? (Please tick) Very Good Good Neutral Poor Very Poor No Opinion 3. What comments do you have about the event you just attended? 4. What is your overall impression of the Cambridge Science Festival? (Please tick) Very Good Good Neutral Poor Very Poor No Opinion 5. What was the most successful element of the Festival for you (and why)? 6. What was the least successful element of the Festival for you (and why)? 5. What was the most successful element of the Festival for you (and why)? On-site evaluation form: p.1 (pt.2) 6. What was the least successful element of the Festival for you (and why)? To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements? 7. I felt I was able to participate actively in the Science Festival. Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree No Opinion 8. I am interested in further investigating scientific topics I encountered at the Festival. Strongly Disagree Disagree Neutral Agree Strongly Agree No Opinion 9. What, if anything, do you feel you have gained from taking part in the Festival? On-site evaluation form: p.2 (pt.1) 10. How would you rate your general level of interest in science outside of the Science Festival? Strongly interested Interested Neutral Not interested Strongly interested No Opinion / Not Sure 11. What is the highest level of education you have completed? GCSE equivalent or less A-level or equivalent First Degree 12. If you are willing, please tell us your postcode Postgraduate Degree ______________________ 13. Please indicate the age and genders of all people in your party: 0-15 yrs 16 -25 yrs 26-39 yrs 40-64 yrs 65 yrs + No. of females No. of males 14. Would you describe yourself or anyone in the group you visited the Festival with as disabled? Yes o No o 15. Please indicate the ethnic origins of all people in your party: Asian or Black or Chinese Mixed Asian British Black British Number of people White Other On-site evaluation form: p.2 (pt.2) 16. How did you find out about the Festival? (Please tick all that apply) Already on mailing list o Work o Online web page Poster o Library o Word of mouth Local press o School o Social media Local interest group o Family / friend o o o o 17. Please give your email address to be included in our emailing list for future public events at the University of Cambridge: ………………………………………………………………………………………. 18. Would you be willing to participate in further online evaluation of the Cambridge Science Festival? Yes o No o If yes, please specify contact details if not provided above: ……………………………………………. Your email address will be stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. We will only contact you 1) regarding the University of Cambridge and Cambridge College public events, if you have indicated you would like to receive updates 2) for evaluation and research purposes, if you have indicated you are willing to participate in further evaluation of the festival. We will not share or transfer the information you have provided for any other purpose. Please hand this form to a steward or send it to: Festivals and Outreach Assistant, Office of External Affairs and Communications, The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, CB2 1RP Analysing Evaluation Data: first thoughts • Closed-ended, scale items intended to gain comparable snapshot of visitors’ views. • Quite general, open-ended questions designed to allow visitors to provide guidance about what they think is most important to feed back. Analysing Evaluation Data: first thoughts • Questions 1, 2 and 3 about the event just attended will be of most immediate interest to presenters and organisers • Other questions may be of interest once placed within the context of overall trends in festival visitors’ responses. – e.g., Is satisfaction with the festival overall higher for attendees at particular events?) Calculating mean satisfaction with event • Previous year’s mean satisfaction ratings overall are around ‘4.5’. Calculate your event’s mean response by: 1. Apply values to the different response options (‘1’ for very poor to ‘5’ for very good) 2. Sum all values for your sample. 3. Divide by the number of respondents. Analysing Evaluation Results: Qualitative Survey Responses • Qualitative responses can be analysed as well, either quantitatively or qualitatively: – Qual.: Organise responses into categories and themes, identifying representative examples of each category or theme. – Quant.: Can identify ‘codes’ or categories, then apply these deductively to the different responses to assess the prevalence of a particular category of response. Impact Evalua'on Good Impact Evaluation • Is SYSTEMATIC • Tells you how and why particular aspects of activity are effective – NOT a binary ‘good’/‘bad’ or ‘successful’/‘unsuccessful’ result. • You don’t learn anything from binary results – A ‘successful’ project can always develop the good aspects of their practice further – There will be specific aspects of an ‘unsuccessful’ project or method that were ineffective (and should be avoided in future projects) – Either way, it is important to have some specifics! Evaluating Impacts: Context • Full-scale evaluation research unrealistic as a continuous activity for most institutions. – May need to bring in external expertise – May need to develop additional training / skills inhouse Recommended approach: 1. At Minimum: Engage in Reflective Practice and use Audience Feedback Forms (Sampling!) Evaluating Impacts: Context 2. At minimum: Specify intended outcomes and specific connections between content and delivery approach and these outcomes. (check against current research / theory and other practitioners’ evaluations) Evaluating Impacts: Context § If possible, formative evaluation before full public rollout of an activity. Ø e.g. focus groups, other pre-testing of ideas § If possible, summative evaluation to address 'how' and 'why' an activity worked well / poorly. Ø ‘How’ and ‘why’ hold implications for other activities and for other practitioners (share!) Evaluation Research • Evalua-on = sub-­‐category of 'social research' (thus all principles of social research apply) • Dis-nguishing feature of evalua-on: Focus on objec'ves / claimed outcomes (prac55oners must specify these outcomes) • In order to evaluate them, prac--oner objec-ves should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realis-c and Targeted. Transla'ng Prac''oner Aims into Evalua'on Research Ques'ons • The evalua-on process begins with concepts / ideas that a prac--oner is aiming to deliver or communicate. • Evalua-on measures the degree to which these objec-ves (e.g. 'learning') are realized. The Evalua'on Process: 1st steps • Vital process of translating abstract / general ideas / concepts (e.g. scientific literacy) into concrete, measurable variables. • Easier said than done. • This is called ‘Operationalization’ – consider: • How would you know that a particular kind of change has happened? • Think about what people would say or do if you were successful in achieving your aims. Definition: Evaluation Research Design Process of choosing how to most effectively assess intended outcomes from your activity / intervention. Evaluation Design: Getting Started • matching goals that motivate activity with evaluation methods for assessing goals. • Evaluation design all about making choices. • To make a good choice, you need to know (1) what your evaluation options are and (2) how to decide between those options. Research Design: Getting Started • It is helpful to think of evaluation research methods as tools that offer a set of strengths/limitations that can be used to accomplish range of goals. Assessing Research Quality • Allowing for Negative Findings Ø Can your hypotheses be shown to be wrong with the kind of evidence you are collecting? • Validity Ø What are you really measuring? • Reliability SUMMATIVE EVALUATION: Sampling Introduction to Sampling • Sometimes the whole population of interest will be accessed (e.g. every member of your audience). • But most of the time this would be too difficult or time consuming. • So we usually study just a sample of the cases that we are interested in. (e.g. a few members of your audience) • What is most important in selecting a sample is that it is representative of the population. • When a sample is representative we can make statements / claims about the population based on the sample. What is a Representative Sample? • To be representative, the sample should accurately reflect the whole population of interest. • We cannot fully know how to select a sample that is representative based on what people look like, etc. • Therefore the best we can do is be sure that every member of the population has an equal chance of being included in the sample. • The central principle here is random selection. A Simple Random Sample What is a Representative Sample? • Some random samples are more complex: Ø For example, involving ‘clustering’ or ‘stratifying’. • At minimum, should use systematic sampling (e.g. every 15th person) Non-random Samples (less good) • Types of Non-­‐Probability Sample: • Convenience sampling • Snowball sampling • Quota sampling • Since non-­‐probability samples do not involve Equal Probability of Selec-on, cannot make accurate sta-s-cal statements / claims about whole popula-on. SUMMATIVE EVALUATION: Reviewing the Toolkit The Toolkit • Quantitative Evaluation Methods Are used to answer any counting related question: • How many? What proportion? What percentage? Survey Research Structured Observation of Audiences / Visitors • Qualitative Evaluation Methods Any study involving non-counting data (e.g. words, drawings, etc.) – These can be converted into quantitative data Qualitative Research • Qualitative Interviews • Focus Groups Data Analysis - Must be systematic to avoid tendency to select quotes based on personal bias and preferences. - Can convert qualitative data into quantitative data through content analysis Qualitative Evaluation Design • Qualitative Evaluation Research typically starts with observations – i.e. it is INDUCTIVE. • These observations are then used to generate hypotheses about what is working and why. • This process leads to evaluation research goals such as discovery and exploration. Qualitative Evaluation Design • Inductive research purposes aimed at theorygeneration and discovery support an “emergent” approach to research design. • Very good for formative evaluation to identify what is most likely to be effective with a given audience. • Very good for exploratory evaluation research, when you don’t know much about audience outcomes. Measurement • Operational definitions are required for the more abstract concepts: – A key issue is what will be captured on a particular measure (i.e. ‘what counts?’) – Measurement error is an issue. (i.e. error due to measurement approach/tool) (e.g. important to directly measure relevant variables such as knowledge, e.g. before/after) OVER TO YOU! • What do you think we should be evalua-ng in fes-val-­‐based public engagement? (e.g. feedback versus impact? What kinds of feedback / impact?) Discuss in groups of about 3 using your preliminary defini7ons as a point of discussion. Best Practice in Survey Design Dr. Eric Jensen e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk University of Warwick 90 Survey Design Flaws (Avoid!) • Construct Validity: The soundness of the measures as indicators of the constructs purported to be examined by the investigators • Non-specific effects: Improvements or changes from effects not specific to the factor or treatment under study • Novelty effect: General energizing and uplifting effects of a new, exciting experience • Confounding Variables: Failure to take into account the fact that the experience under study may include more than one component that affects outcome Survey Design Flaws (Avoid!) continued • Demand Characteristics: The tendency of participants to alter their responses in accord with what they believe to be the researchers’ hypothesis • Experimenter expectancy effect: • The tendency of investigators to unintentionally bias the results in accordance with their hypotheses Survey Design Flaws (Avoid!) continued • Response Bias: A bias in subject responding due to the test instrument rather than the subjects’ actual beliefs • Sampling Bias due to non-random sampling: Unintentional sampling of subjects that introduces systematic error or bias into the results Survey Design Flaws (Avoid!) continued • Acquiescence Bias: A bias from respondents’ tendency to agree with statements à Control for this by including reverse wording items on agreement scales “Put me down for whoever comes out ahead in your poll”. Survey Design Issues: Self-Report – what is it good for? Advantage Offers direct access to respondents’ views Disadvantages Validity issues such as: • Response biases such as social desirability • Lack of (self-)conscious awareness • Attributional biases Principles of question design • Survey question responses need to be: Exhaustive – that everyone fits into one category Exclusive – so that everyone fits into only one category (unless specifically required to ‘tick as many as apply). Unambiguous – so that they mean the same to everyone and all responses are comparable. Questions • Beware of social desirability bias: Phrase sensitive questions impartially so respondent can answer truthfully without feeling stigmatised Questions • Ensure you don’t have any double-barrelled questions (e.g., ‘What interested you in visiting the zoo this year and last year?’) • Avoid Leading Questions!!! – Leading questions such as “Do you agree that Durrell is doing important work to save animals from extinction?” Survey Design Quality • Allow for Negative Findings • Validity • Reliability Piloting your Survey • First, you can probe indepth with pilot respondents about some particular questions • Second, the survey in its entirety should be administered to pilot respondents. Piloting your own Questionnaire • Exercise: Design one survey question + response options related to your project as an individual then try out the questions in small group (3 people) and get feedback (mainly at the first level of pilot survey feedback). – Report back on what kinds of changes were recommended Top Tips • Evaluation requires very clear, specific and measurable objectives Beware of ‘Raising Awareness’ and ‘Inspiring Interest’! • Quantitative Methods Get the design right at the beginning! (e.g. pilot testing) • Sampling Equal probability of selection is optimal! Top Tips Surveys Think carefully about questions and limit self-report! Evaluation Design Avoid positive bias and allow for possibility of negative outcomes. QualàQuant. In Survey Design Dr. Eric Jensen e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk University of Warwick 105 Conclusion • Based on all the research I have done, I believe the top impact of fes-val-­‐based public engagement to be CURIOSITY • The key then is to capitalize on this impact by having good systems in place for extending impact beyond the physical and temporal confines of the fes-val. Further Resources on Public Engagement and Informal Learning Impact Evaluation EVALUATING IMPACTS OF PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT AND NON-­‐FORMAL LEARNING SEMINAR / TRAINING SERIES ONLINE! 107 Festival-­‐based Public Engagement Dr Eric Jensen Assistant Professor of Sociology University of Warwick e.jensen@warwick.ac.uk 108