The Government of Japan Officially Defines Power Harassment in the Workplace

March 7, 2012

Practice Group:

Labor and

Employment

The Government of Japan Officially

Defines Power Harassment in the Workplace

By Naoki Watanabe, Grant Tanabe, Makoto Ohsugi

Workplace bullying and power harassment have recently received much attention in the press as a pervasive social issue in Japan, and on January 30, 2012, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

(“ MHLW ”) publicly released a report titled, “Report by the Working Group Roundtable regarding

Workplace Bullying and Harassment” (the “ Report ”). The Report recommends that a company: (1) have a clear message about power harassment from top management; (2) establish a consultation area;

(3) determine the company rules regarding power harassment; (4) prevent reoccurrence through training sessions; (5) recognize the current situation of the company; and (6) announce the company’s policy to all employees.

According to the Report, although the number of power harassment complaints was approximately

6,600 in 2002, it rapidly increased to approximately 39,400 in 2010. Also, in a survey which targeted companies that are listed in the First Section (for large companies) of the Tokyo Stock Exchange, 82% of those companies responded that implementing measures to deal with power harassment is an important part of managing a company, and thus, such companies are highly sensitive to power harassment issues.

However, much progress needs to be made as many employers have either turned a blind eye or have found difficulty in distinguishing between acts of “power harassment” and “appropriate employer guidance in the course of the company’s business.” Therefore, the Report was prepared to bring further attention to the issue and clarify which types of actions constitute power harassment or workplace bullying. Indeed, for the first time, the MHLW defined power harassment in the Report as being, “an act by an employee using his position of seniority or relationship with a co-worker which causes such co-worker mental or physical stress or a degradation of the working environment beyond the appropriate scope of the company’s business.”

The Report is divided into three sections: (i) “Why should a company deal with workplace bullying and harassment;” (ii) “What kind of actions should be eliminated from the workplace;” and (iii) “How workplace power harassment may be eliminated.” These sections, and our brief comments and recommendations in relation to each section, are discussed below.

1. “Why Should a Company Deal with Workplace Bullying and Harassment”

The Report notes that the workplace is where people spend most of their lifetime and become engaged in various work and social relationships. If an employee is exposed to power harassment, he will not only lose his incentive to work, but also could be forced to take a long absence or retire due to mental health reasons. Furthermore, the problem is not only for such directly affected employees, but also for other employees who have heard or seen the power harassment – their incentive to work would decrease and as a result, the productivity of the whole workplace would be impaired.

From a legal perspective, in addition to being liable for any systemic power harassment, the company would be liable for any specific actions which constitute power harassment of a manager over his

The Government of Japan Officially Defines Power

Harassment in the Workplace subordinate, because the company would have failed in its duties to supervise and create a safe environment for the employee.

Therefore, it is clear that not only from a legal perspective, but from a business perspective, it is critical for a company to actively deal with power harassment in the workplace to avoid the risk of a labor management dispute and to maintain a harmonious working environment.

2. “What Kind of Actions Should be Eliminated from the Workplace”

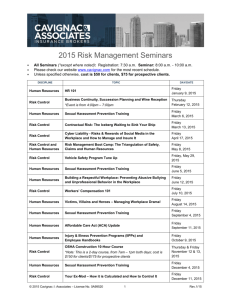

The Report categorizes power harassment in the following six (6) categories:

Actions Examples

1. Assault (physical abuse)

2. Intimidation, defamation, insulting, or slander (mental abuse)

Punching, kicking, and throwing items

Statements such as “Can’t you properly do the work like this?” or “If you were with any other company, you would be fired!”

3. Isolation, ostracization, or neglect (cutting off from any human relationships)

4. Forcing the employee to perform certain tasks which are clearly unnecessary for the business of the company, impossible to be performed, or interfere and interrupt with their normal duties (“excessive work demands”)

Not receiving all-company notices

Not inviting to summer party or year-end party

Isolating the person in a cubicle without giving him any work

Ordering the person to prepare a daily report even if it is unnecessary for business purposes

Forcing the person to achieve excessive quotas

Transferring the person from a high executive position to a receptionist’s position

5. Ordering an employee to perform menial tasks that are unreasonable in relation to the company’s business or tasks which are far below the employee’s ability or experience.

Also includes not providing any work at all for the employee. (“insufficient work demands”)

6. Excessively inquiring into the private affairs of the employee (invasion of privacy)

Paying particular attention to a certain employee only because such employee belongs to a particular political party

Excessively inquiring into an employee’s private disputes unrelated to the company

Among the aforementioned categories of actions, the “physical abuse” actions (No. 1) such as assault are thought to exceed the appropriate scope of business even if it relates to the performance of business. Also, the “mental abuse” actions, such as intimidation or defamation (No. 2) or isolation or neglect (No. 3), are believed, in principle, to exceed the appropriate scope of business.

2

The Government of Japan Officially Defines Power

Harassment in the Workplace

On the other hand, in relation to the “excessive work demands” (No. 4), in a recent case, the Tokyo

District Court found that the employer was not liable for damages for instructing an employee to prepare daily reports regarding his daily job duties because such reports were required as part of the employee’s training. There may be cases where an employer has high expectations for an employee and in helping the employee progress in his or her career, the employer may be justified in demanding that the employee perform certain tasks for his or her career development.

With regard to the “insufficient work demands” (No. 5), there may also be situations where work is given to the employee that is not related to his ability or experience, but for his career development.

In relation to the “invasion of privacy” (No. 6), since communication at the workplace is essential in maintaining a healthy working environment, employees often have daily conversations about various private matters, and therefore, it is often difficult to distinguish between “private” and “non-private” matters.

Accordingly, with regard to Nos. 4 through 6, employers may have difficulty in determining the distinction between actions that constitute power harassment versus actions that fall under appropriate company guidance and training. Therefore, employers should obtain internal consensus and specify to employees which actions would fall under Nos. 4 though 6.

3. “How Power Harassment May be Eliminated”

The Report makes the following recommendations as preventive measures and solutions to address power harassment:

A. Message from the top – Top management should expressly state that power harassment must be eliminated from the workplace.

B. Establish a consultation area – Employers should (1) establish a point of contact for consultation inside and outside the company and designate the responsible persons; and (2) liaise with external professionals (including industry counselors).

C. Determine the rules – Employers should (1) incorporate the relevant provisions in the Rules

of Employment and/or a labor management agreement; and (2) prepare policies and guidelines

regarding preventive measures and solutions.

D. Prevent reoccurrence and educate employees – If an incident is discovered, the employer should provide training sessions to prevent the reoccurrence of power harassment by that

individual.

E. Recognition of the actual situation within the company – Employers should have employees

fill out questionnaires to assess their current situation.

F. Announcement – Make company-wide announcements regarding its policies and relevant

training sessions.

These measures emphasize improving awareness of power harassment in the workplace. With regard to employee education, companies should establish a policy to increase awareness of power harassment issues through internal or other training sessions (e.g., once every two months) customized to the employee’s position within the company. Although the preventive measures recommended in the Report may differ depending on the size of the company, a court of law would likely review the company’s preventive measures in determining whether the company violated its duty to supervise and provide a safe workplace for the employee. Therefore, in establishing a company policy on power harassment, companies should seek the advice of outside counsel.

3

The Government of Japan Officially Defines Power

Harassment in the Workplace

To create a working environment where employees can easily obtain access to consultation for any potential power harassment incidents, the company should have both internal and external consultation services available. For example, the Report indicates that Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd. has a designated law firm to provide consultation services on every Thursday and Friday of the week. Also, with regard to any disciplinary action taken against an employee, proper fact-gathering and other procedures need to be conducted to avoid any potential labor management dispute. It is therefore critical that a company contact outside counsel at the earliest stage of a power harassment incident.

Authors:

Naoki Watanabe naoki.watanabe@klgates.com

+ 81.3.6205.3609

Grant Tanabe grant.tanabe@klgates.com

+ 81.3.6205.3607

Makoto Ohsugi makoto.ohsugi@klgates.com

+ 81.3.6205.3606

4