Insurance Coverage Alert Aerojet Cases That Potentially Limit Coverage for Environmental Liabilities

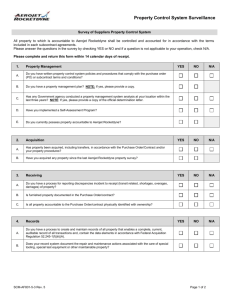

advertisement

Insurance Coverage Alert April 2008 Authors: Michael S. Nelson +1.412.355.6245 michael.nelson@klgates.com Emily S. Gomez +1.412.355.6374 emily.gomez@klgates.com K&L Gates comprises approximately 1,500 lawyers in 24 offices located in North America, Europe and Asia, and represents capital markets participants, entrepreneurs, growth and middle market companies, leading FORTUNE 100 and FTSE 100 global corporations and public sector entities. For more information, please visit www.klgates.com. www.klgates.com Aerojet is the Latest in a Line of California Cases That Potentially Limit Coverage for Environmental Liabilities The California Court of Appeal’s recent decision in Aerojet-General Corp. v. Comm. Union Ins. Co., 155 Cal. App. 4th 132 (2007) may serve as a basis for insurers to try to limit California policyholders’ rights to coverage for costs associated with environmental remediation. Specifically, in Aerojet, the Court of Appeal ruled that cleanup costs from a settlement negotiated after regulators filed suit alleging liability for CERCLA response costs and other costs arising out of alleged groundwater contamination were not “damages” subject to indemnification under the corporation’s excess liability policies. Id. at 143. Relying on a prior decision from the Supreme Court of California that defined “damages” as “money ordered by a court to be paid,” the Court of Appeal concluded that “because the [trial] court did not order the payment of any money, the [insurers] had no duty under the terms of their policies to indemnify Aerojet for the costs it incurred in implementing its settlement agreement.” Id. at 145-46. History Beginning in 2000, regulatory agencies filed suits against Aerojet alleging its liability for costs relating to groundwater contamination in the San Gabriel Valley. Id. at 135. Aerojet gave its insurers notice of each lawsuit, though no excess carrier accepted the company’s tender of defense or indemnity. Aerojet subsequently settled the lawsuits for a total of $175 million, an amount that exceeded the total amount of its primary and excess insurance for each year in the period of 1958 to 1970. Id. When Aerojet demanded payment pursuant to its policies, all excess carriers denied liability. Consequently, Aerojet filed suit for breach of contract. The excess liability policies at issue all contained insuring agreements and attachment of liability clauses that were substantially similar. The insuring agreements required the insurer to indemnify Aerojet for “all sums which the Assured shall become legally obligated to pay, or by final judgment be adjudged to pay, to any person or persons as damages . . . .” Id. at 137 (emphasis added). The attachment of liability clauses provided that the excess insurers were not liable to pay until either the underlying insurers admitted liability or the insured was held liable to pay by a final judgment an amount which exceeded the underlying insurance and the underlying insurers had paid or been held liable to pay their full limits. Id. After the close of discovery, each of the insurer-defendants filed separate motions for summary judgment. The trial court granted summary judgment based on two of those motions, holding that the “language in the policies at issue providing for payment of sums Aerojet becomes legally obligated to pay as damages is limited to sums Aerojet was ordered by pay by the court. The monies paid by Aerojet in settlement do not meet this definition.” Id. at 139. Aerojet appealed the summary judgment ruling. Foster-Gardner and Its Progeny The Court of Appeal began its analysis by revisiting a line of environmental insurance coverage cases that arose out of the California Supreme Court’s 1998 decision in FosterGardner, Inc. v. National Union Fire Ins. Co., 959 P.2d 265 (Cal. 1998). In Foster-Gardner, the Insurance Coverage Alert court determined that an insurer’s duty to defend was limited to civil actions prosecuted in a court. Focusing on the phrase “suit seeking damages” in the coverage grant, the California Supreme Court concluded that a proceeding conducted by an administrative agency pursuant to an environmental statute was not a “suit” that gave rise to a defense duty, but was a “claim” that the insurer had authority to investigate and settle but no duty to defend under the policy. Id. at 265. The California Supreme Court took this strict interpretive approach one step further in Certain Underwriters at Lloyd’s of London v. Superior Court, 16 P.3d 94 (Cal. 2001) (“Powerine I”). Like FosterGardner, that case involved a coverage dispute that arose out of administrative orders directing the policyholder to remediate contaminated third-party property. In Powerine I, the California Supreme Court, relying on the policy language at issue, held that the insurer’s duty to indemnify “all sums that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages” is limited to “money ordered by a court.” Id. at 94. To support its position, the court developed the so-called “Foster-Gardner syllogism,” which states that: The duty to defend is broader than the duty to indemnify. The duty to defend is not broad enough to extend beyond a “suit,” i.e., a civil action prosecuted in a court, but rather is limited thereto. A fortiori, the duty to indemnify is not broad enough to extend beyond “damages,” i.e., money ordered by a court, but rather is limited thereto. Id. at 94.1 The court went on to find that, based on the specific policy language before it, no legal obligation to pay “damages” arose absent an order of court and, therefore, the duty to indemnify did not “extend to any expenses required by an administrative agency pursuant to an environmental statute. . . .” Id. In two separate but related cases, the court applied Powerine I to determine the indemnity obligations of excess insurers. In Powerine Oil Co., Inc. v. Superior Court, 118 P.3d 589 (Cal. 2005) (“Powerine II”), the court found that an excess insurer had a duty to indemnify costs arising out of an administrative cleanup order because the “ultimate net loss” definition 1 Of course, the major premise of this proposition is based on conclusions reached in the Foster-Gardner decision that are arguably inconsistent with both the policy language and the reasonable expectations of the insured at the time the policy was underwritten. referenced in the coverage grant included the amount the insured became obligated to pay “either through adjudication or compromise, and shall also include . . . expenses . . . for litigation, settlement, adjustment and investigation of claims and suits . . . .” Id. at 589 (emphasis in original). By contrast, in County of San Diego v. Ace Property & Casualty Ins. Co., 118 P.3d 607 (Cal. 2005) (“County of San Diego”), the coverage dispute arose out of policy language that required the insurer to indemnify “all sums which the insured is obligated to pay by reason of liability imposed by law or assumed under contract or agreement [arising from] damages caused by personal injuries or the destruction or loss of use of tangible property.” Id. Analyzing this language, the court found that “damages” was the “sole term of limitation of the indemnity obligation under the insuring agreement” and, therefore, settlement costs agreed to outside the context of a court suit were not subject to an indemnity obligation under the excess policy. Id. The Court of Appeal Applied FosterGardner and its Progeny to the Aerojet Policies Foster-Gardner and the cases that followed were limited to administrative claims and did not purport to decide whether settlement costs negotiated within the context of a lawsuit constituted “damages” for the purposes of an insurance contract. Despite the limited scope of Foster-Gardner and its progeny, the Court of Appeal in Aerojet found that those cases were controlling given the contract language at issue. The Court of Appeal noted that nothing in the record indicated that the trial court ordered Aerojet to make any payments, nor was there any evidence that the parties to the settlement agreement sought for the terms of the agreement to be entered as a judgment entered as part of the trial court record. Id. at 144.2 The Court also noted that, unlike the policies at issue in Powerine II, there was no language in the Aerojet policies suggesting that indemnity is owed for anything other than “damages.” Id. at 143. As a result, the court concluded that the settlement costs were outside the scope of indemnity coverage. Id. at 144. The court indicated that it was aware of a letter written by Aerojet’s counsel proposing that the settlement agreement be entered as a stipulated judgment to protect against the coverage problems potentially created by Powerine I. Id. at 147. 2 April 2008 | 2 Insurance Coverage Alert Next, the Court of Appeal examined the attachment of liability clause in the insurance contracts. Aerojet argued that the settlement agreement constituted a final judgment for purposes of the clause, noting that the plaintiffs in the underlying action withdrew their complaints after settlements were reached. Id. at 146. The court rejected this argument, observing that the plaintiffs did not dismiss their actions with prejudice. Because the plaintiffs were free to file suit again, the court found that there was no legal bar to further litigation and the settlement agreement could not be seen to act as a final judgment. Id. Lastly, the court examined whether the insurer defendants were equitably estopped from relying on the terms of the indemnity agreements on the grounds that Aerojet kept the insurers apprised of its settlement strategy and negotiations, and reasonably relied on them to voice any concerns or objections. Id. The court dismissed this argument outright, noting that there was no evidence that the insurers intended for Aerojet to settle the underlying lawsuits, nor any evidence that Aerojet could reasonably have believed the insurers intended such. Conclusion The Aerojet decision is the latest in a line of California appellate cases that insurers will argue serves to limit an insurer’s obligations to defend and indemnify settlements resolving environmental damage claims. It is important to note that Aerojet and its predecessors are inapplicable in disputes arising out of policies that require the insurer to defend and indemnify against something more than just “damages.” Moreover, it is not certain that Aerojet is applicable outside of the environmental context. In coverage disputes arising out of claims alleging bodily injury as a result of exposure to asbestos or silica dust, for example, the underlying claims are typically litigated in court, although they are frequently settled before a verdict is rendered following a trial. It is unclear whether those types of settlements would need to be memorialized in a judgment entered on the docket in order to satisfy Aerojet. At a minimum, this decision will lend support to unreasonable interpretations of policy language advanced by insurers who seek to escape their coverage obligations. K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin, and in Beijing (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP Beijing Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining our London office; a Taiwan general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis - Taiwan Commercial Law Offices) which practices from our Taipei office; and a Hong Kong general partnership (Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis, Solicitors) which practices from our Hong Kong office. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication/newsletter is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. Data Protection Act 1998—We may contact you from time to time with information on Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP seminars and with our regular newsletters, which may be of interest to you. We will not provide your details to any third parties. Please e-mail london@klgates. com if you would prefer not to receive this information. ©1996-2008 Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP. All Rights Reserved. April 2008 | 3