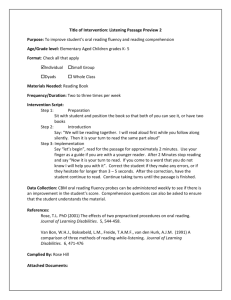

Effective Instruction for Middle School Students with Reading Difficulties:

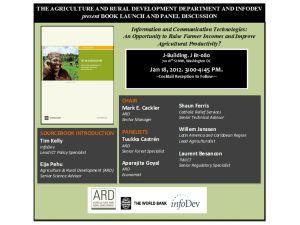

advertisement