Social Sensing and Its Display

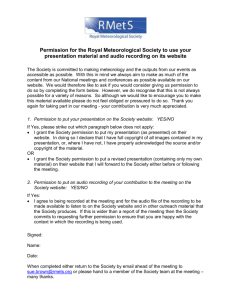

advertisement