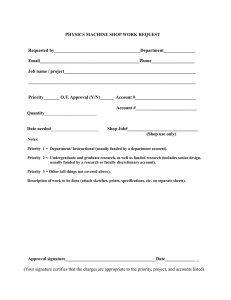

partial fulfillment July LJSThIAL

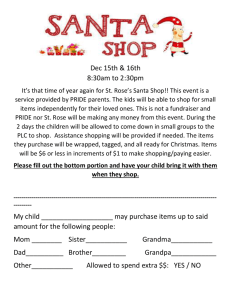

advertisement