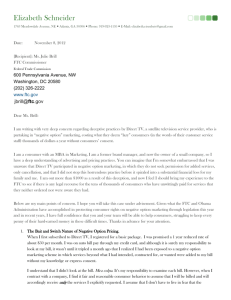

I. Introduction

advertisement