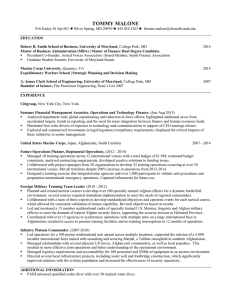

Alison Long

advertisement