Document 13665503

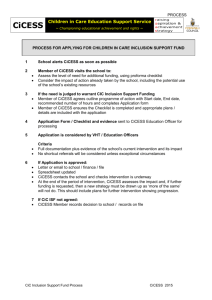

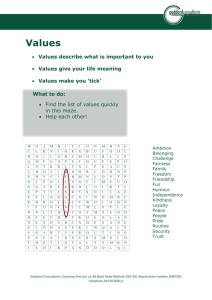

advertisement