The Delaware Chancery Court Enforces the

advertisement

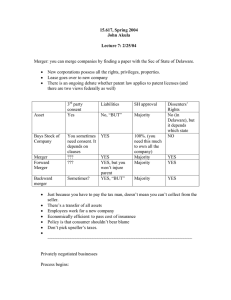

November 9, 2011 Practice Groups: Corporate Mergers & Acquisitions Commercial Disputes Deal Litigation The Delaware Chancery Court Enforces the Express Obligation to Negotiate in Good Faith Awards PharmAthene Half of Net Profits from Potentially Multibillion Dollar Smallpox Cure On September 22, 2011 after a three-week trial, Vice Chancellor Parsons rendered a 117-page decision in PharmAthene, Inc. v. Siga Technologies, Inc., Civil Action No. 2627-VCP, Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware, that awarded 50 percent of the net profits of a drug that cures smallpox to K&L Gates client PharmAthene, Inc., a biodefense company. The defendant in the case was Siga Technologies Inc., a company controlled by Ronald Perlman. The first sale of the drug took place after the trial when the government entered into a $433 million contract to purchase the drug and announced a mandate to make $2.4 billion of additional purchases. Background of the Case The case arose out of a failed merger between PharmAthene and Siga. Siga had been developing a promising drug for smallpox, but had experienced difficulties in its development efforts and, in late 2005, found that it required a substantial financial investment to bring the drug to market. Because it lacked the financial wherewithal to fund that investment itself, it entered into discussions with PharmAthene for a possible collaboration. While PharmAthene wanted to discuss a merger of the companies, Siga insisted on working out a framework for a license agreement before discussing a merger because Siga was in immediate need of cash to continue its development work and previous merger discussions between the parties had failed. After working out the terms of a term sheet for a license agreement, the parties turned to negotiating a merger agreement, which was ultimately signed in June 2006. Due to the cash needs of Siga in the interim, however, the parties had entered into a $3 million bridge loan agreement. Both the bridge loan and merger agreements stated that if the merger did not close the parties would “negotiate in good faith with the intention of executing a definitive License Agreement in accordance with the terms set forth in the License Agreement Term Sheet.” The two-page term sheet was attached as an exhibit to both agreements. In addition to fairly detailed economic terms, it had a footer at the bottom of each page that said “Non Binding Terms.” During 2006, Siga achieved a number of important development milestones in connection with the smallpox drug, but the closing of the merger was delayed during the SEC review of Siga’s proxy statement for the merger. Ultimately, the merger did not close by the drop-dead date specified in the merger agreement and Siga terminated the agreement, after which the parties commenced license negotiations as had been agreed as a fallback position if the merger did not close. The negotiations quickly became contentious. Siga contended that because the drug had just been found to be safe in humans and to cure smallpox in primates it was now a $3-5 billion drug and therefore Siga was entitled to economic terms that were significantly more favorable than those specified in the license agreement term sheet -- for instance, $300 million instead of $16 million in The Delaware Chancery Court Enforces the Express Obligation to Negotiate in Good Faith upfront and milestone payments and an increased royalty percentage on sales of the drug with a 50/50 profit split thereafter. While PharmAthene indicated its willingness to negotiate modified economic terms in order to avoid a dispute, discussions broke down and PharmAthene sued claiming (1) the term sheet constituted a binding license agreement; (2) that Siga failed to negotiate in good faith in accordance with the terms of the term sheet; (3) promissory estoppel; and (4) unjust enrichment. The Court’s Decision on Liability The trial was conducted in Delaware in January 2011. After trial, the Court found that the term sheet was not a binding agreement although it accorded the “non binding” footer “only limited weight.” Instead, the Court relied upon the merger agreement’s 90-day exclusive period for negotiations and the bridge loan’s two-year maturity date to find that the parties never “intended to bind themselves to enter into a license strictly conforming” to the term sheet. The Court also found that even though the parties “appear to have agreed on the main economic terms of a license agreement” it was still missing material terms. However, the Court found that the parties’ obligation to negotiate in good faith in accordance with the terms of the term sheet obligated them to negotiate “a license agreement with the same or similar terms.” As a result, the Court found that Siga’s proposal was made in bad faith and also that Siga was liable under the doctrine of promissory estoppel. The Remedy Finding the appropriate remedy was a significant issue in this case. PharmAthene had requested three alternative remedies: (1) specific performance; (2) expectation damages; and (3) a stream of future payments from the proceeds of the sales of the drug. While the Court noted that under Delaware law “specific performance is likely a permissible remedy for breach of an agreement to negotiate in good faith” it declined to do so here because “the character of the performance would force the Court into an onerous enforcement or supervisory role.” Under Delaware law, expectation damages as of the date of the breach can be awarded for breach of a covenant to negotiate in good faith. However, since at the time of trial the drug had yet to be sold (though there was evidence that Siga was about to receive a very large contract) the Court concluded expectation damages would be too speculative. PharmAthene also proposed an equitable payment stream based on the proceeds of the sales of the drug. If there were no sales, PharmAthene would get nothing. If there were sales worth billions of dollars as anticipated, PharmAthene would share in the profits. This is the remedy the Court adopted. Using its power as a court of equity, it imposed a constructive trust on any profits Siga receives after Siga retains the first $40 million to reimburse it for costs of development. 50 percent of subsequent net profits go to PharmAthene. The Court found that based on internal Siga documents and PharmAthene’s offer of a 50/50 profit split, the parties would have arrived at these economic terms in a good faith negotiation. Finally, because the Court found that Siga acted in bad faith it awarded PharmAthene one-third of its attorneys and expert witnesses fees. Points of Interest Simply labeling a document non-binding does not preclude an obligation to negotiate in good faith and may not be sufficient to avoid liability, especially if the document is attached to a binding 2 The Delaware Chancery Court Enforces the Express Obligation to Negotiate in Good Faith agreement. On the other hand, a very detailed term sheet that contains all the major business terms may still be found to lack material terms from a legal standpoint and therefore be unenforceable. A court’s willingness to enforce good faith obligations is highly fact specific and will vary depending on the jurisdiction. Therefore, the choice of law and jurisdiction can determine the outcome of the case. Roger Crane of the New York office and Chris Carton of the Newark office represent PharmAthene, Inc. Author: Roger R. Crane roger.crane@klgates.com +1.212.536.4064 Additional Contacts: Peter N. Flocos peter.flocos@klgates.com +1.212.536.4025 Whitney J. Smith whitney.smith@klgates.com +1.212.536.3930 3