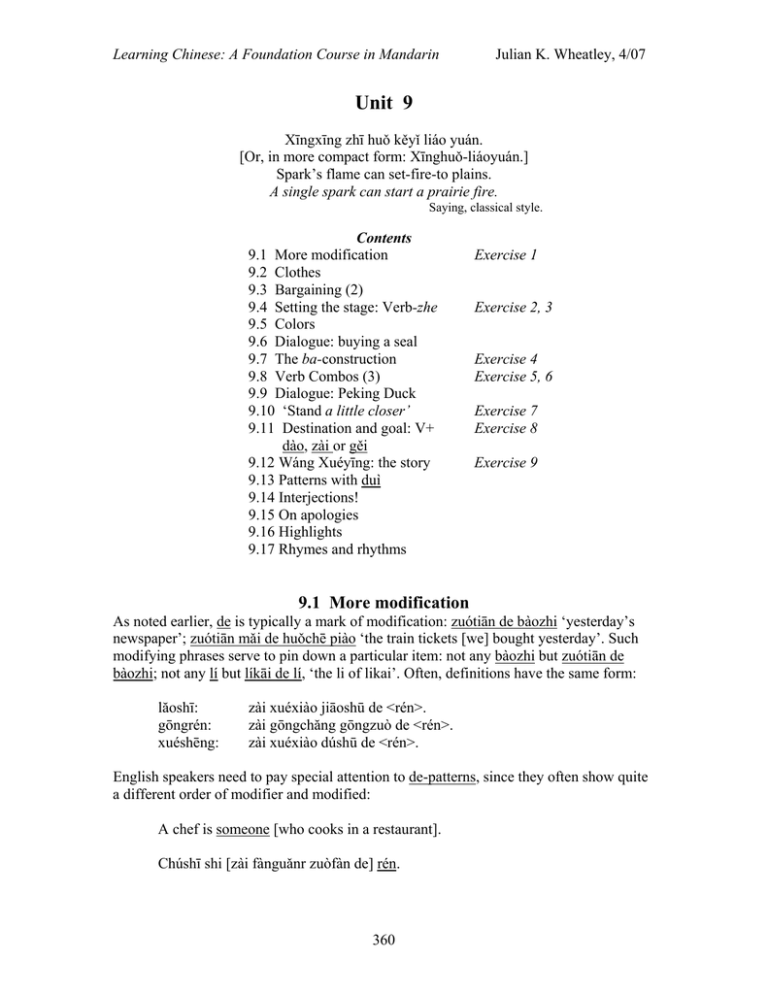

Unit 9

advertisement