Competing Visions for U.S. Grand Strategy T Barry R. Posen and

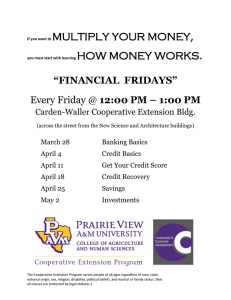

advertisement