ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF NEW UNIONIZATION ON PRIVATE SECTOR EMPLOYERS: 1984 –2001* J D

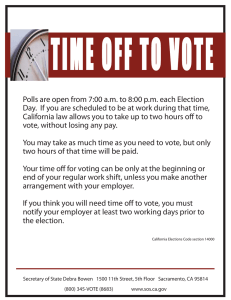

advertisement