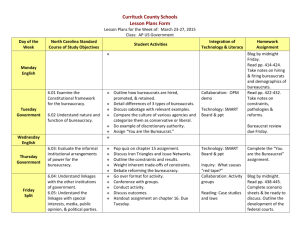

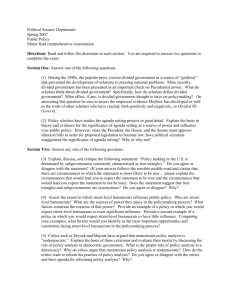

Management of Bureaucrats and Public Service

advertisement