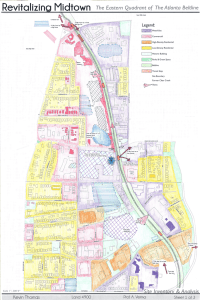

Atlanta BeltLine Health Impact Assessment

advertisement