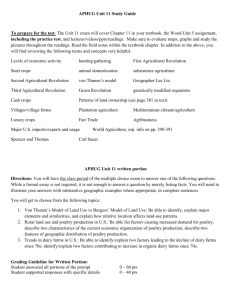

A Comparison of the Structure and Practice of Dairy Farming

advertisement