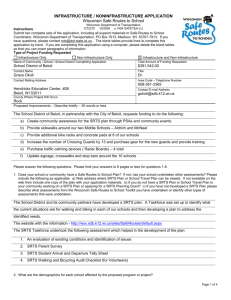

Safe Routes to School Local School Project A health evaluation at 10

advertisement