BINGE EATING DISORDER AND ASSOCIATED PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITY CONFER INCREASED RISK... PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES:

advertisement

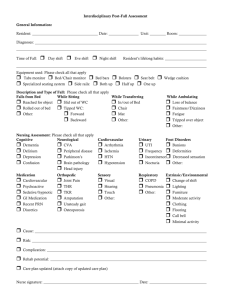

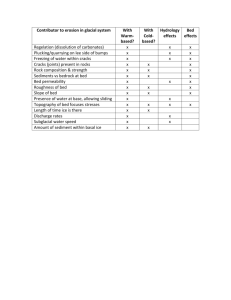

BINGE EATING DISORDER AND ASSOCIATED PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITY CONFER INCREASED RISK OF PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES: RESULTS FROM A NATIONAL SAMPLE. Summar Reslan, B.A. 1, Karen K. Saules, Ph.D. 1, Daniel Eisenberg, Ph.D. 2 Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology 1 University of Michigan, School of Public Health 2 Introduction Results Binge eating disorder (BED) is defined as experiencing recurrent episodes of binge eating in a discrete period of time accompanied by a loss of control over eating and two of five associated symptoms. BED is prevalent on college campuses with approximately 5% meeting full BED criteria (Ivezaj et al., 2010) and roughly 38% engaging in problematic binge eating behavior (Mintz et al., 1998). Many studies have investigated the utilization of mental health services on college campuses (Eisenberg et al., 2007), but few have focused on the impact that BED may have on service utilization. Among treatment seeking individuals who have BED, 74% report having at least one lifetime, and 43% report having at least one current, psychiatric disorder (Grilo et al., 2009). We thus hypothesized that those utilizing services will be more likely to have comorbid psychological problems. Approximately 5.4% (N = 465) of participants met BED criteria in this sample. Compensatory behaviors were common among those with BED (55%), but less than 1% of the sample met full bulimia nervosa criteria. Logistic regression analyses indicated that relative to their non-BED counterparts, those with BED had an increased likelihood for psychological service utilization, OR = 1.966; CI.95 [1.707, 2.266], p < .001, and medical health care utilization, OR = 1.298; CI.95 [1.044, 1.614], p < .05. Amongst those with BED, engaging in compensatory behaviors also increased psychological service utilization, OR = 1.744, CI.95 [1.318, 2.319], p < .001. BED in combination with anxiety or depression increased likelihood of psychological service utilization. BED in combination with depression and binge drinking increased likelihood of medical health care utilization within the past 12 months. Green = % utilizing psychological services within the past 12 months Discussion PARTICIPANTS/PROCEDURES: Data were drawn from the 2009 Healthy Minds Study (HMS), a national sample of college students. HMS evaluates a range of mental health topics such as the prevalence and disease burden of mental health conditions. This database is composed of 8,597 undergraduate and graduate students from 15 colleges and universities who completed an online survey. This sample was predominately female (58.9%). The rate of BED in this sample is comparable to other studies (e.g., Grucza et al., 2007; Ivezaj et al., 2010), suggesting that these findings may generalize to other samples. Research indicates those who binge eat have higher emotional dysregulation than those who do not binge eat (Claes et al., 2005). Utilizing rates of psychological service utilization as an index of emotional dysregulation, results indicate that emotional dysregulation is heightened among those with BED who also engage in compensatory behaviors or who have other psychological comorbidities in comparison to those with BED alone and those without BED. MEASURES: Demographics Depression and anxiety screening questions were drawn from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999) (CAS; Wechler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994) Yellow = % using medical services within the last 12 months ***BED plus comorbidities significantly differ from all other groups for both psychological and medical service utilization, p < .001. Method BED items were drawn from the SCID-I/NP (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). BED was screened positive if a liberal criterion of binge episodes 1-2 times per week was met, as well as endorsing two associated symptoms of BED. Binge drinking items were drawn from the College Alcohol Study Contact: shabhab1@emich.edu Yellow = % utilizing medical services within the last 12 months Green = % utilizing psychological services within the last 12 months ***Psychological Services: BED plus compensatory behaviors significantly differ from no BED, p < .001, and BED alone, p < .01. BED no compensatory behaviors significantly differ from No BED, p < .001. Health care utilization items were drawn from the Healthcare for ***Medical Services: BED alone significantly differ from No BED, p < .001. Communities Study (Wells, Sturm, & Burnam, 2004). Items assessed psychological and medical health care utilization Presented at the 2010 Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine within the past 12 months Consistent with our hypothesis, those utilizing both psychological and medical services were more likely to have comorbid psychological problems. These results indicate that individuals with BED may not perceive this pathological eating pattern as severe enough to warrant the utilization of services until it becomes comorbid with other psychological problems. Those with BED who do not engage in compensatory behaviors utilize medical services more so than those without BED and those with BED plus compensatory behaviors. It is unclear how this relationship is impacted by weight. To help clarify this relationship, the HMS 2010 survey will collect information on height and weight of respondents. BINGE EATING DISORDER AND ASSOCIATED PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITY CONFER INCREASED RISK OF PHYSICAL AND MENTAL HEALTH CARE UTILIZATION ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES: RESULTS FROM A NATIONAL SAMPLE. Summar Reslan, B.A. 1, Karen K. Saules, Ph.D. 1, Daniel Eisenberg, Ph.D. 2 Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology 1 University of Michigan, School of Public Health 2 References • Claes, L., Vandereycken, W., & Vertommen, H. (2005). Impulsivity-related traits in eating disorder patients. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 739-749. • Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Gollust, S.E. (2007). Help-seeking and access to mental health care in a university student population. Medical Care, 45(7), 584-601. First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., Williams, J.B.W. (2002). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP). New York, NY: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute. Grilo, C. M., White, M. A., & Masheb, R. M. (2009). DSM-IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(3), 228-234. • • • Grucza, R.A., Przybeck, T.R., Cloninger, C.R. (2007). Prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in a community sample. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48(2), 124-131. • Hudson, J.I., Hiripi, E., Pope, H.G., & Kessler, R.C. (2007). The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry, 61, 348-358. • Ivezaj, V., Saules, K.K., Hoodin, F., Alschuler, K., Angelella, N., Collings, A.S., Saunders-Scott, D., Wiedemann, A. (2010). The relationship between binge eating and weight status on depression, anxiety, and body image among a diverse college sample: A focus on bi/multiracial women. Eating Behaviors, 11, 18-24. • Mintz, L.B., & Betz, N.E. (1988). Prevalence and correlates of eating disordered behaviors among undergraduate women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(4), 463-471. • Spitzer, R.L., Yanovski, S.Z., & Marcus, M.D. (1994). Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns – Revised. Mclean, VA: Behavioral Measurement and Database Services (Producer) BRS Search (Vendor). • Wechsler, H., Davenport, A., Dowdall, G., Moeykens, B., & Castillo, S. (1994). Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college. Journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1672-1677. • Wells, K.B., Sturm, R., & Burnam, A. (2004). National Survey of Alcohol, Drug, and Mental Health Problems [Healthcare for Communities], 2000-2001. [Codebook].