Validating the Behavioral Economic Choice Paradigm to Assess Food Preferences

advertisement

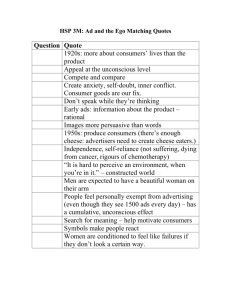

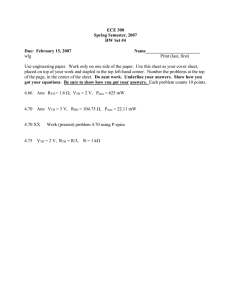

Validating the Behavioral Economic Choice Paradigm to Assess Food Preferences Summar 1 Reslan , Karen K. 1 Saules , and Mark K. 2 Greenwald Eastern Michigan University, Department of Psychology 1 Wayne State University, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences 2 Introduction Behavioral economic theory is a useful framework for analyzing factors influencing choice. Historically, human behavioral economic research has focused on drug choice. In light of parallels between eating and addictive behavior, economic choice paradigms may also be valuable for understanding food-maintained behavior. The primary objective of this investigation was to validate a human laboratory model of food-appetitive behavior in healthy individuals. Methods Female non-smokers of normal BMI (mean + SD = 26.7 + 6.0) were recruited. To control pre-session food satiation, subjects were asked to refrain from eating two hours prior to the experiment. Two independent groups completed either two experimental sessions conducted over consecutive 30-min intervals (n=17), or one concurrent food choice session (n=21) conducted over 30 min. Unit food amount per trial was equated on mass during consecutive sessions (1 Dove BarTM= 6 Teddy GrahamsTM), and concurrent sessions (1 Hershey KissTM = 1 Kraft cheese cube). In each session, subjects could work for units of food on an 11-trial progressive ratio schedule (FRs = 5, 12, 33, 100, 180, 340, 540, 835, 1220, 1660, 2275). Subjects were told that unit food amount would be constant, but response requirement (unit price, UP) would increase on successive trials. Upon completion, subjects were asked to consume all food earned. Group-percent food choices across UPs were fit with a standard exponential demand equation: Y= log(L) * exp(−AX) Results Demand for High-Sugar/High-Fat (Dove BarTM) vs. LowSugar/Low-Fat (Teddy GrahamsTM) in Consecutive Choice Sessions During consecutive choice sessions, demand for the high-sugar/high-fat food option was slightly but significantly more inelastic than the low-sugar/low-fat food, Pmax (UP at which slope of curve equals –1) = 663 vs. 494, F(1,17) = 6.45, p < .05. Demand for High-Sugar/High-Fat (Hershey KissTM ) versus LowSugar/High-Fat (Cheese Cube) During Concurrent Choice Sessions During concurrent choice sessions, overall-sample (n=21) demand for the high-sugar/high-fat (Hershey KissTM) and low-sugar/high-fat food (cheese cube) did not significantly differ (Pmax= 449 vs. 388), but there were significant independent subgroup differences in concurrent food choice. Restrained vs. Unrestrained Eaters (TFEQ; Stunkard & Messick, 1985) Demand for the high-sugar/high-fat food was more inelastic for Restrained (n=12) than Unrestrained eaters (n=9), Pmax= 632 vs. 297, F(1,15) = 27.36, p < .001 (left panel), whereas for low-sugar/high-fat food the opposite pattern was observed (more inelastic for Unrestrained than Restrained eaters), Pmax= 278 vs. 711, F(1,15) = 11.91, p < .01 (right panel). Contact: shabhab1@emich.edu High-BMI (>25) vs. Low-BMI (<25) Subjects Demand for the high-sugar/high-fat food (left panel) was more inelastic among subjects with High BMI (n=11) vs. Low-BMI (n=9), Pmax = 586 vs. 351, F(1,16) = 14.71, p < .02. In contrast, demand for the low-sugar/high-fat food (right panel) was more inelastic for Low- vs. High-BMI subjects, Pmax = 577 vs. 339, F(1,17) = 5.06,p < .04. Chocolate/cheese choice differences were significant only in High-BMI subjects. Discussion High vs. Low-Impulsive Subjects (Food Delay Discounting Task) Subjects completed a chocolate delay discounting task (1 Hershey KissTM now vs. 1 bag of 75 chocolates in [5 to 180] min) and were classified from their discounting rates (k values) as High-Impulsive (n=9) or Low-Impulsive (n=11). Demand for the high-sugar/high-fat option (left panel) was more elastic for High- vs. Low-Impulsive subjects, Pmax = 407 vs. 546, F(1,17) = 5.89, p < .05. Similarly, demand for the low-sugar/high-fat option (right panel) was more elastic for High- vs. Low-Impulsive subjects, Pmax = 217 vs. 594, F(1,16) = 26.73, p < .0001. • Demand curves for more palatable food (i.e., high-sugar/high-fat) were generated in the direction expected More demand-inelastic (price-resistant) behavior was evident for highsugar/high-fat food. The relative value of this option depended on the choice procedure (consecutive vs. concurrent) and the food comparator (low-sugar/lowfat vs. low-sugar/high-fat). Further parametric studies would be useful. • Significant group differences in food choice were noted for restrained eaters, high-impulsive, and high-BMI subjects Restrained eaters’ chocolate demand was higher than cheese, but the reverse pattern was observed for Unrestrained eaters. This is consistent with the notion that attempts to restrict eating may enhance desire for more palatable foods. High food-impulsive subjects worked less for both food types, consistent with desiring smaller, more immediate outcomes. High BMI subjects defended consumption of chocolate more, but cheese less, relative to Low BMI subjects. This is consistent with the idea that obese individuals prefer sweet foods to maintain energy intake. • There may be other clinically important individual difference and psychopharmacological effects on food choice behavior The next goal of this programmatic work is to determine the effects of nicotine and nicotine abstinence on food-appetitive behavior among weight concerned smokers (who are mostly female). Supported in part by Joe Young, Sr. Funds (State of Michigan)